Copyright 2009 by Tad Friend

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

First eBook Edition: September 2009

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

AUTHORS NOTE

I have changed the names of a few people: the Viscontis and Giovanna Viscontis boyfriends; Sally Cottone and her family; Melanie Grayboden and her family; Francesca; and Christine Wells.

Portions of this book were previously published, in different form, in The New Yorker and The Paris Review.

Copyright acknowledgments appear on page .

ISBN: 978-0-316-07144-4

For my family

We said good-bye with a highball

Then I got high as a steeple.

But we were intelligent people

No tears, no fuss,

Hurray for us.

So thanks for the memory,

And strictly entre nous,

Darling, how are you?

And how are all the little dreams

That never did come true?

RALPH RAINGER AND LEO ROBIN,

Thanks for the Memory

F ROM AN UPSTAIRS window, I see my father walking away down his snowy lawn. He moves uncertainly, his hands cupped around his eyes like an Arctic explorer in a whiteout. It takes a moment to realize that he is peering through my mothers old Olympus camera, aiming it here and there. The set of his shoulders suggests dissatisfaction with what he sees this Christmas season: the bare apple trees, the frozen pond. Turning to face the house at last, he lowers himself onto one knee like a hopeful fianc and pans across the stone exterior, slowly now. Watching him out there leaves me lonely.

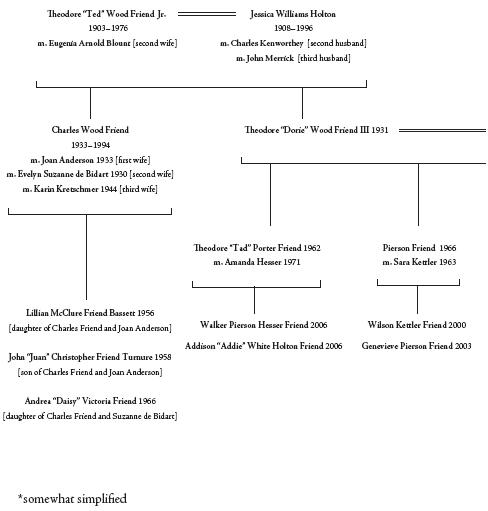

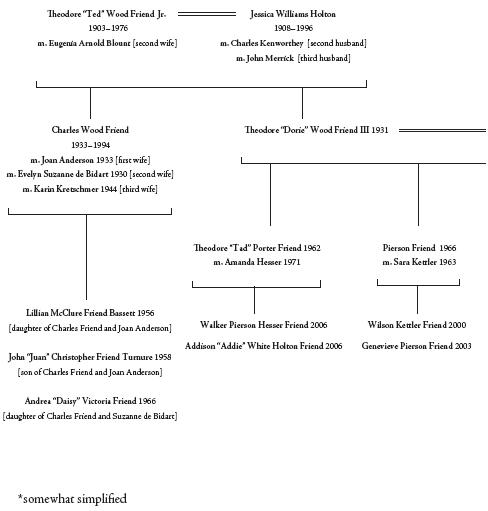

My father, Dorie Friend, is a historian and a highly rational man; his Easter Islandsize head is stuffed with knowledge. In our family, he was in charge of logic and money. He husbanded our declining fortunes, a decline that, as he recognized, mirrored the broader Wasp ebb: the outflow of maids and grandfather clocks and cocktail shakers brimming with gin.

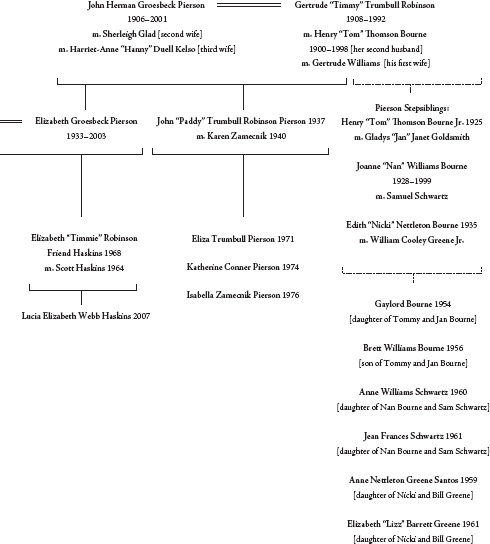

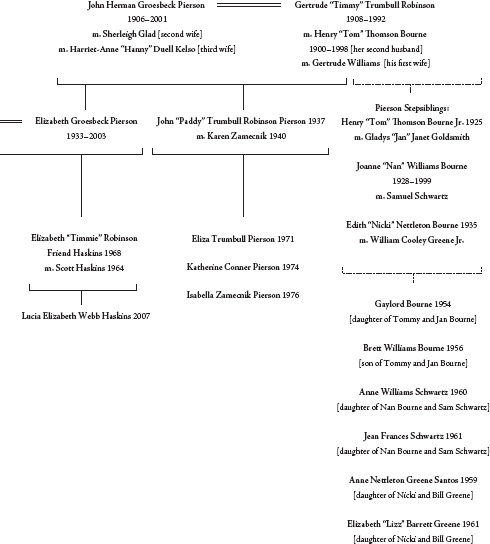

My mother, who utterly ignored this decline, was in charge of everything else. She set the tone. Elizabeth Pierson Friend was Lib to her oldest friends, classmates at Smith who possessed all the graces. They were stylish and sparkling women, prepared by birth and since birth to charm the Burmese or Nigerian ambassador, but Mom was particularly conscientious. She took occasions so seriously. After much ado, she e-mailed her friends about one party, I had settled on a periwinkle blue dress: Fortuny-like silk pleats in a tea-length skirt, horizontal tucks in a long-sleeved tunic top. A necklace of eight strands, each a different size, of silver-gray freshwater pearls, twisted to almost choker length Slim and vivacious and determined, with a pouf of chestnut hair and snapping blue eyes, she drew you out at the table, exclaiming at just the right moment, and her own conversation built to jubilant punch lines.

There was the story about how she had received a terrific rush in her early twenties, with a date every night, including a series with a tremendously tall young man who later supervised the secret bombing of Cambodia. And then, suddenly, the phone didnt ring for two weeks: And I thought, So this is menopause. There was the story about a trip to India, during which it became necessary for her to hide a suitors turban in an icebox. Before you could wonder, Why an icebox, exactly? she cried, So there I was, dancing cheek to cheek with a Sikh! When my father first heard that story overheard it, actually, from an adjoining booth in a New Haven diner he thought, Who is that horrible woman? When he heard it for the second time, years afterward, it was too late.

She pounced past your defenses. When I was in my twenties, a married woman Id been idly flirting with at a gallery opening in New York introduced herself to my mother as we all took the elevator down and said, Ive been talking to your son all night. Hes fascinating. I reddened, embarrassed but pleased.

You should see the rest of the family, Mom replied, instantly. You had to love her for that.

She spelled basic words as if she were Corsican (snug was cosi; gloves were mittons); trespassed wherever a stylish driveway beckoned; sobbed if she caught a bad cold. Her character was chatoyant, like a cats eyes, candid and then suddenly bleached and desolate. But her darker recesses were usually masked by virtuosity: a gifted cook, painter, and designer, she had also shown early promise as a poet. As a sophomore at Smith, she came in second to Sylvia Plath in a poetry contest judged by W. H. Auden (who, when my mother was introduced to him a year later, delighted her by saying, I believe I have read your verse). She longed to best Plath, her nemesis. Later, though, she would toss her head and say, Just as well I didnt win. Head in the oven, and so forth.

From time to time, I find myself studying a photograph of her taken in the summer of 1962, when she was pregnant with me, the first of her three children. She stands on the lawn in a blue maternity dress, looking pale and watchful. A soccer ball rests under her bare right foot. Soccer was my fathers sport, and would be mine, but she liked to flash out into the yard and perform the high trap. He would fling the ball into the air, and Mom would judge its fall perfectly and smother it with her right sole. And then, in triumph, shed depart to rule her own realm, which consisted of tennis, tomato sandwiches, gossip, bread-and-butter letters, chore lists, conviviality, wit, and worrying. It all fell under the heading of keeping the house in order, wherever the house was. Her last campaign began in 1989, with this house in the Philadelphia suburb of Villanova: the one being photographed by my father.

After years without a home to make her own in Buffalo, in the sixties, my parents had no income to speak of, and then for nearly twenty years they lived first in an imposing pile belonging to Swarthmore College, when my father was the colleges president, and later in a rented bungalow the Villanova house was her epic work. An anonymous fieldstone relic at first, the place soon grew thick with her, with the snares and honeypots she concealed in plain sight: the bottom kitchen drawer pull that rewarded you with a small collapsible stepladder; the closets stuffed with Christmas gifts, so that you couldnt approach a doorknob without having her call out, from three rooms away, Ooh, ooh dont go in there! Walking through the Villanova house was like reading a series of Rorschach blots that inked out her emotional history (except that she hated blots of any sort). She had it all planned, having long considered how best to arrange a house and its contents, including us.