A LSO BY D AVID M ARANISS

Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story

Barack Obama: The Story

Into the Story: A Writers Journey through Life, Politics, Sports and Loss

Rome 1960: The Summer Olympics That Stirred the World

Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseballs Last Hero

They Marched into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967

When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi

The Clinton Enigma: A Four-and-a-Half-Minute Speech Reveals This Presidents Entire Life

First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton

The Prince of Tennessee: Al Gore Meets His Fate (with Ellen Nakashima)

Tell Newt to Shut Up! (with Michael Weisskopf)

The Red Scare and My Father

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2019 by David Maraniss

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition May 2019

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Paul J. Dippolito

Jacket design by Michael Nagin

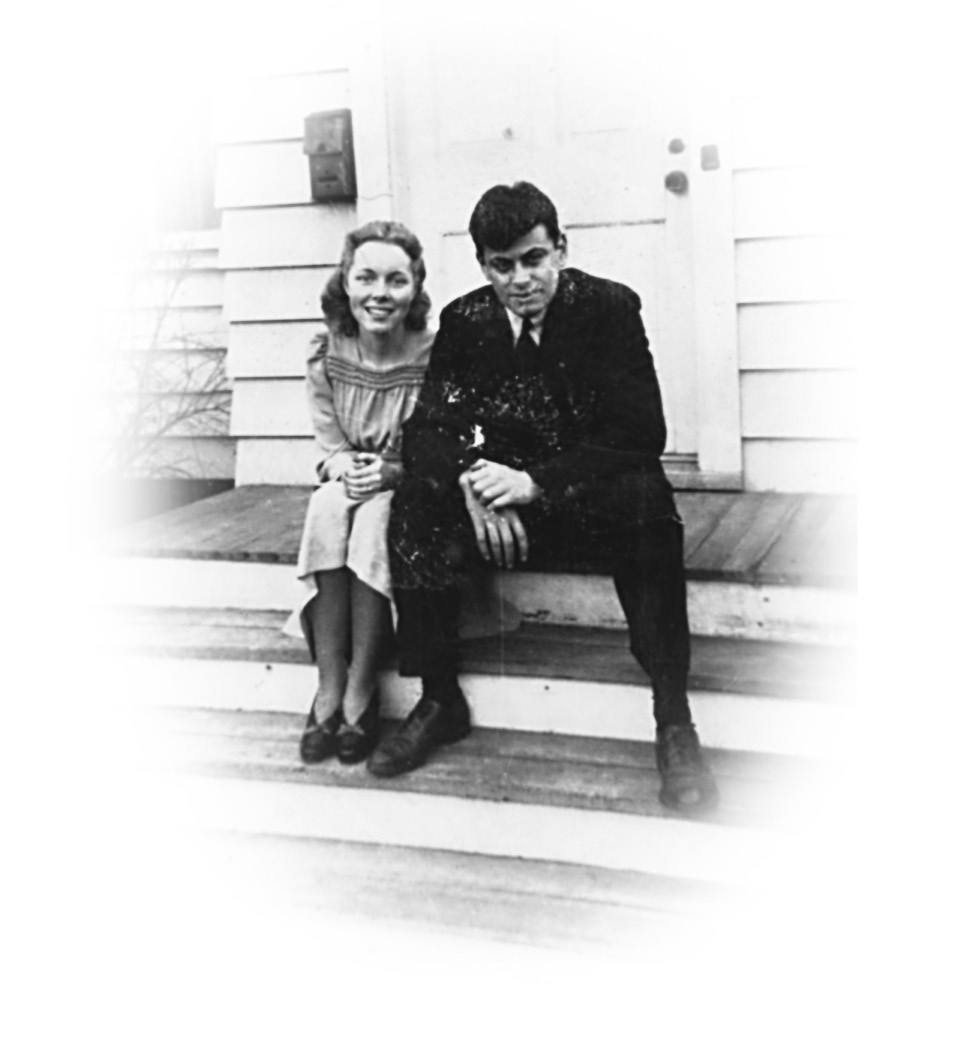

Jacket photograph Courtesy of the Author

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-5011-7837-5

ISBN 978-1-5011-7838-2 (ebook)

To my parents, Mary and Elliott Maraniss, with eternal gratitude

Authors Note

Think of this story as a wheel.

The hearing in Room 740 is the hub where all the spokes connect.

But the truth, the first truth, probably, is that we are all connected, watching one another. Even the trees.

Arthur Miller , Timebends

PART ONE

Watching One Another

1

The Imperfect S

I WAS NOT yet three years old and have no memory of anything that happened that day. It was March 12, 1952. My father, Elliott Maraniss, sat at the witness table in Room 740 of the Federal Building in Detroit, where he had been subpoenaed to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. As the questioning neared the end, he asked whether he could read a statement. There were several points he wanted to make about his freedoms as an American citizen, as an army veteran who had commanded an all-black company during World War II, and as a newspaperman. John Stephens Wood of Georgia, chairman of the committee, rejected this request. We dont permit statements, Wood said. If you have one written there, we shall be glad to have it filed with the clerk.

The chairmans denial was arbitrary. If a witness was compliant, named names, repented, and humbly sought absolution, then a statement might be allowed. But my father was not compliant. He challenged the committees definition of what it meant to be American and invoked the Fifth Amendment in refusing to answer questions about his political activities, so his statement was submittedunreadto the committee clerk, and from there essentially buried and forgotten. No mention was made of it in newspaper accounts the next day, nor was it included as an addendum to the hearing transcript published by the U.S. Government Printing Office months later. It was just one more document entombed in history, eventually stored in the vast collections of the National Archives in downtown Washington, the same vaulted building that holds original copies of the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rightsthe foundation trinity of the American idea.

By the time I looked at the committees old files, sixty-three years had passed since the hearing. My father was dead, as were Chairman Wood and all the other players in that long-ago drama. But the moment came alive to me as soon as I opened a folder in Series 3, Box 32, of the HUAC files and found the statement. Three pages. Typed and dated. When I began reading the first page, it was not the writing that struck me but the physical aspect of the words on the page, starting with the first letter of the first word of the first line:

Statement of Elliott Maraniss.

That was the line, though in the original, the capital S of Statement jumped up a half-space, as capital letters on manual typewriters sometimes did. And in typing his first name, it looked as though my father twice hit the neighboring r key instead of the t , and rather than x-ing it out or starting over again he had just gone back and typed two t s over the r s.

The pages that followed were resonant with meaning. My father was trying to explain who he was, what he believed in, and the predicament in which he found himself. But it was the composition of that prosaic first line that hit me hardest, the imperfect S .

This seems to be how life often works; the smallest gestures and details can assume the most significance. Now I could place myself in 1952, sitting there in Detroit as my father composed his statement only days after being fired from his newspaper job in the wake of a subpoena and the testimony of an FBI informant who had identified him as a member, or former member, of the local Communist Party. I could see my dad at the typewriter, a place where I had watched him so often in later years. He was a hunt-and-peck typist, jabbing away at an old dusk-gray upright with his index fingers, a Pall Mall (and later Viceroy) burning beside him in a heavy glass ashtray strewn with half-smoked and twice-smoked cigarette butts. There was a certain violence and velocity, thrilling but harmless, to his typing. He was messy and noisy, accompanying his work with a low, vibrating hum, thinking wordlessly aloud. He punched so hard and fast that ribbons frayed and keys stuck. He slapped the carriage return with the confidence of an old-school newspaperman. He was always making typos and correcting them by x-ing them out or typing over them, like those r s and t s.

It is invariably thrilling to discover an illuminating document during the research process of writing a book, but in this case that sensation was overtaken by pangs of a sons regret. Looking at the typed statement, I started to absorb, finally, what I had never fully allowed myself to feel before: the pain and disorientation of what my father had endured. For decades I had desensitized myself to what it must have been like for him. I had always considered him in the moment, rarely if ever relating present circumstances to the context of his past. As much as I loved him, I had never tried to put myself in his place during those years when he was in the crucible, living through what must have been the most trying and transformative experience of his life. Until I saw the imperfect S .

THE RESEARCH VISITS to the National Archives came at the beginning of my long-overdue attempt to understand what had happened to my father and our family and the country during what has come to be known as the McCarthy era, named for the demagogic senator who emblemized the anticommunist Red Scare fury of the early 1950s. Joseph McCarthy himself enters this story only as a shadowy presence in the background. As far as I can tell, my father never encountered him, and McCarthy never uttered his name. Their connection was more poetic than literal. McCarthy came from Wisconsin and died in 1957. That is the same year my father emerged from five years of being blacklisted and our familys fortunes changed for the better when he was hired by the Capital Times in Wisconsin, a progressive Madison newspaper that made its name fighting McCarthy.

Next page