N ot being the offspring of a family with any claim to distinction, not coming from a background I felt any need to live up to, or live down, I have always been impatient with those who express emotional attachment to the past. Man might not yet be perfect, but it suited me to think he was better than he had ever been. The belief that he was once wiser and kinder, more courageous and more beautiful, that he once had instinctive understanding we have lost, I dismissed as sentimental myth.

And yet I had no right to such an attitude, for I once knew a woman who was living proof of the validity of that belief. Perhaps because middle age is upon me (how painful it is to admit it like this in writing) and I recognize that more of my life now lies behind me than is likely to extend ahead, I can face other realities, which, until now, the arrogance of youth helped me ignore, and at last tell this story that has nagged at me like a suppressed but highly insistent truth all these years.

The woman I write of may well be the last noble savage to be described by an eyewitness. She does not fit into the sociological theories we use to classify our native Indians and make them manageable or, at least, excuse our inability to manage them. Not only did she survive into the twentieth century by her ancient Indian skills and values, but she shamed that world, showing up the hollowness of many of its most dearly held pretensions about itself.

Perhaps only the eyes of the child that I was could have discerned her greatness and yet, as I bring my present awareness to re-examine that old evidence, her dimensions have grown, until now, out of all the summers of my childhood, she emerges to stand in the foreground.

I was taken to the Laurentian village where she lived for the first of my remembered summers in 1927. The lake lay less than a hundred miles north of Montreal, but it seemed very remote to me then because of the dusty four-hour train trip during which I slithered restlessly about on the varnished rattan seats while my mother gave me oranges to peel, pointed out the engine pulling us each time the train went around a turn, and warned me to sit small when the conductor passed to collect the tickets.

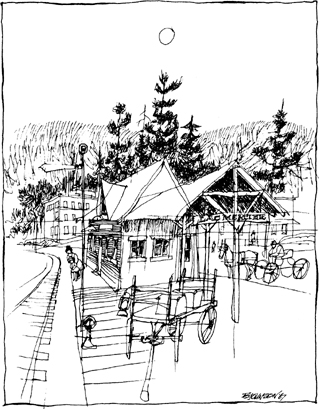

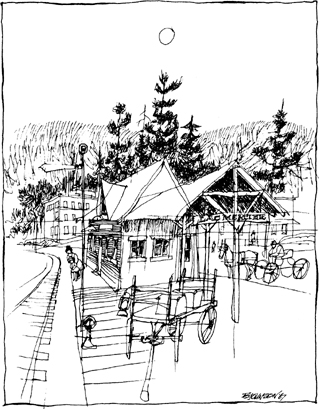

The lake was shaped like a boomerang, two miles long with the Canadian Pacific Railway tracks edging the outer rim, the railway station and village snuggling at the curve. The dirt road into the village followed the tracks as far as the station, then swerved sharply away to continue on to the big lake three miles farther. As I try to describe it, I see that the lake and the road really resembled two boomerangs placed back to back.

The village did not differ importantly from others in the Laurentians where Montrealers were already building summer cottages or vacationing in clapboard hotels, and it offered only one diversion by which one could tick off the passing of the summer days. Each evening the summer people and a few of the villagers gathered on the platform of the railway station to watch the arrival of the Montreal train, then moved leisurely up to the general store a few yards away to await the sorting of the mail. Sundays divided the weeks as fathers came from town and the tiny Roman Catholic church rang its bell at hourly intervals all morning to summon the faithful to Mass. In those first years, before the big white structure that still dominates the lake was built, the church was too small to hold everyone, and the hill behind it was crowded with hatted, high-heeled girls who climbed gingerly up the slope, helped by their coated escorts, so they could see, as well as hear, the service through the open windows.

Being of Irish Protestant parents I never attended services, but since the cottage we rented every summer for a decade was next door to the church, I was often in it. The door was always open. If I was around when the caretaker rang the bell with reasonable accuracy at seven oclock mornings and evenings, he would let me help him pull the thick, rough rope. If I was around, as I had no right to be, at other times when he was not there, I would pump at a pedal of the organ in the balcony until I finally extracted a booming note that would draw my mothers attention to my absence and bring her running.

The thirty French-Canadian families that lived in the village the year round, many in unpainted, weather-grayed boxes on stilts, eked out a marginal living. They had small vegetable gardens, every inch of which had been cleared by hand from the rocky mountain slopes. A few had cows from which we got our milk still warm. My mother, having grown up on a farm in central Ireland, was delighted by its natural state; she remarked repeatedly on its wholesomeness and flavor which she believed were spoiled in the pasteurized milk sold in the city. Also, being unseparated, it need only stand a while in the ice box to acquire a top layer of cream thick enough for whipping.

Serving the summer people was, of course, the main employment of the villagers: they worked in the hotels, did small carpentry jobs, scraped the dirt roads, cut ice from the lake for the sawdust-filled ice sheds, took in laundry, sent their daughters to work in the houses of the better-off vacationers and their children to pick and sell the wild strawberries, raspberries and blueberries that, consecutively, seemed to last the summer. Skiing had not yet opened the Laurentians to winter activity, and the men went off to the lumber camps in November to send home the fifteen dollars a month by which their families survived between summers.

Life had not always been quite so hard for them. An industry had provided more regular employment, but it had closed down the year before our arrival. Known only as the chemical plant, it had extracted chemicals from wood, and bits of charcoal were strewn everywhere like pebbles. For many years rumors persisted that it would re-open, but it never did, and its vast sheds and ovens became irresistible to all us children. Each afternoon terminated with the kind of ritual play that distinguishes children from adults, and makes a youngster glad he has not yet crossed the dividing line as we yes, we, for even I managed occasionally to escape my mothers watchfulness on the pretext of going to the general store flung chunks of charcoal high up the sloping tin roofs, listened as long as we dared to their bumpy trip back down, then ran to hide in the nearby woods before the only Englishman who lived year round in the village, and had, naturally, been left in charge of things by the departed English management, came out of his house the other side of the creek and shouted threateningly at us. Gradually, through the years, his interest lapsed (perhaps his stipend for looking after the property also decreased) and he went on to chicken farming while the sheds disappeared, board by board, and the tin, sheet by sheet, to repair the houses of the villagers and the children, deprived of the climax to their drama, gathered there less and less.