I, Rigoberta Mench

An Indian woman in Guatemala

Edited and Introduced by Elisabeth Burgos-Debray

Translated by Ann Wright

Translation Verso 1984

First published as Me Llamo Rigoberta Mench Y Asi Me Naci La Concienca

Editions Gallimard and Elisabeth Burgos 1983

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN: 978-1-84467-471-8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

CONTENTS

TRANSLATORS NOTE

Rigobertas narration reflects the different influences on her life. It is a mixture of Spanish learned from nuns and full of biblical associations; of Spanish learned in the political struggle replete with revolutionary terms; and, most of all, Spanish which is heavily coloured by the linguistic constructions of her native Quich and full of the imagery of nature and community traditions.

She has learned the language of the culture which oppresses her in order to fight itto fight for her peopleand to help us understand her own world. In doing so, she has created a form of expression which is full of passion, poetry and wisdom. Sometimes, however, the wealth of memories and associations which come tumbling out in this spontaneous narrative leave the reader a little confused as to chronology and details of events.

The problem of translation was how to retain the vitality, and often beautiful simplicity, of Rigobertas words, but aim for clarity at the same time. I have tried, as far as possible, to stay with Rigobertas original phrasing; changing and reordering only where I thought the meaning could not be readily understood. Hence, Ive left the repetitions, tense irregularities, and sometimes convoluted sentences which come from Rigobertas search to find the right expression in Spanish. Words have been left in Spanish or Quich, where they are objects or concepts for which we have no precise equivalent. The two most obvious words in this category are ladino and compaero . Although ladino ostensibly means a person of mixed race or a Spanish-speaking Indian, in this context it also implies someone who represents a system which oppresses the Indianfirst under Spanish rule and then under the succession of brutal governments of the landed oligarchy. So a word like half-caste would be inadequate. Hence Rigobertas fathers invention ladinizar (to ladinize , or become like a ladino ) which is a mixture of ladino and latinizar (to latinize), and has both racial and religious connotations. I think it is clear that the word compaero , which literally means companion, changes its meaning during the book. Rigoberta initially uses it for her friends, and her neighbours in the community. But as the political commitment of both Rigoberta and her village grows, it becomes comrade, a fellow fighter in the struggle. She uses it for the militants in the trade unions, the CUC and the political organisations. The compaeros de la montana are the guerrillas. From these two words comes the rather unwieldy compaero ladino .

Rigoberta has a mission. Her words want us to understand and react. I only hope that I have been able to do justice to the power of their message. I will have done that if I can convey the impact they had on me when first I read them.

Ann Wright

INTRODUCTION

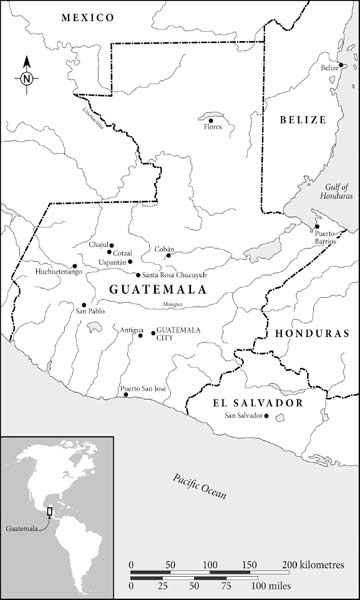

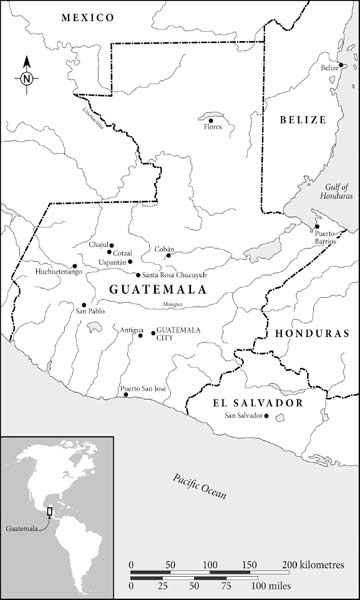

This book tells the life story of Rigoberta Mench, a Quich Indian woman and a member of one of the largest of the twenty-two ethnic groups in Guatemala. She was born in the hamlet of Chimel, near San Miguel de Uspantn, which is the capital of the north-western province of El Quich.

Rigoberta Mench is twenty-three years old. She tells her story in Spanish, a language which she has spoken for only three years. Her life story is an account of contemporary history rather than of Guatemala itself. It is in that sense that it is exemplary: she speaks for all the Indians of the American continent. What she tells us of her relationship with nature, life, death and her community has already been said by the Indians of North America, those of Central America and those of South America. The cultural discrimination she has suffered is something that all the continents Indians have been suffering ever since the Spanish conquest. The voice of Rigoberta Mench allows the defeated to speak. She is a privileged witness: she has survived the genocide that destroyed her family and community and is stubbornly determined to break the silence and to confront the systematic extermination of her people. She refuses to let us forget. Words are her only weapons. That is why she resolved to learn Spanish and break out of the linguistic isolation into which the Indians retreated in order to preserve their culture.

Rigoberta learned the language of her oppressors in order to use it against them. For her, appropriating the Spanish language is an act which can change the course of history because it is the result of a decision: Spanish was a language which was forced upon her, but it has become a weapon in her struggle. She decided to speak in order to tell of the oppression her people have been suffering for almost five hundred years, so that the sacrifices made by her community and her family will not have been made in vain.

She will not let us forget and insists on showing us what we have always refused to see. We Latin Americans are only too ready to denounce the unequal relations that exist between ourselves and North America, but we tend to forget that we too are oppressors and that we too are involved in relations that can only be described as colonial . Without any fear of exaggeration, it could be said that, especially in countries with a large Indian population, there is an internal colonialism which works to the detriment of the indigenous population. The ease with which North America dominates so-called Latin America is to a large extent a result of the collusion afforded it by this internal colonialism. So long as these relations persist, the countries of Latin America will not be countries in any real sense of the word, and they will therefore remain vulnerable. That is why we have to listen to Rigoberta Menchs appeal and allow ourselves to be guided by a voice whose inner cadences are so pregnant with meaning that we actually seem to hear her speaking and can almost hear her breathing. Her voice is so heart-rendingly beautiful because it speaks to us of every facet of the life of a people and their oppressed culture. But Rigoberta Menchs story does not consist solely of heart-rending moments. Quietly, but proudly, she leads us into her own cultural world, a world in which the sacred and the profane constantly mingle, in which worship and domestic life are one and the same, in which every gesture has a pre-established purpose and in which everything has a meaning. Within that culture, everything is determined in advance; everything that occurs in the present can be explained in terms of the past and has to be ritualized so as to be integrated into everyday life, which is itself a ritual. As we listen to her voice, we have to look deep into our own souls for it awakens sensations and feelings which we, caught up as we are in an inhuman and artificial world, thought were lost for ever. Her story is overwhelming because what she has to say is simple and true. As she speaks, we enter a strikingly different world which is poetic and often tragic, a world which has forged the thought of a great popular leader. In telling the story of her life, Rigoberta Mench is also issuing a manifesto on behalf of an ethnic group. She proclaims her allegiance to that group, but she also asserts her determination to subordinate her life to one thing. As a popular leader, her one ambition is to devote her life to overthrowing the relations of domination and exclusion which characterize internal colonialism. She and her people are taken into account only when their labour power is needed; culturally, they are discriminated against and rejected. Rigoberta Menchs struggle is a struggle to modify and break the bonds that link her and her people to the ladinos , and that inevitably implies changing the world. She is in no sense advocating a racial struggle, much less refusing to accept the irreversible fact of the existence of the ladinos . She is fighting for the recognition of her culture, for acceptance of the fact that it is different and for her peoples rightful share of power.