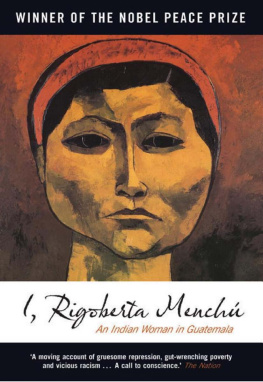

WHO IS RIGOBERTA MENCH?

GREG GRANDIN

This edition first published by Verso 2011

Greg Grandin 2011

originally appeared in The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-84467-850-1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

Contents

Preface

I reread I, Rigoberta Mench last year, after Verso asked me to write an introduction for a new edition, having not taught or turned to the book for quite awhile. The controversy that had engulfed the memoir in the late 1990s, which included charges that Mench misrepresented some aspects of her life, had increased the class time needed to teach it and there were other good, quick illustrations of Cold War terror in Central America one could assign, such as Marc Danners Massacre at El Mozote, for instance. The intensity of the accusations and questions asked about Menchs storyWhat was true? What wasnt? Who wrote it? Who, really, was Rigoberta Mench and what did she want?seems specific to the fixations of a time that was, in the US at least, more innocent: the last skirmish in the pre-9/11 culture wars. Today, students and scholars who have time to work through the always vexed relationship between history and memory continue to find the book useful. But the tribunes of culture and opinion can breezily dismiss it as a hoax, or as an example of social or political witness stories that turns out to be works of fiction, as the New Yorker recently did, along with James Freys discredited A Million Little Pieces. This is regrettable, for subsequent researchby individual scholars (see the suggestions for further reading) as well as sprawling, multi-year investigations by two truth commissions, one run by the Catholic Church and the other by the United Nationshas largely vindicated Menchs version of events.

When I returned to the book, I half expected to find in Mench a left-wing John Galt, a character with no inner life, a pure propagandist. Thats not the case. Throughout the narrative, but especially toward its end as Mench moves toward exile and retrospection, her testimony reveals dissonant impulses, pleasure in the middle of terror and currents of despair running under surface triumphalism. Mench, a semi-literate twenty-three-year-old with a few years of basic education, one of the few survivors of a slaughtered peasant family, conjures a battleground where her political battles seem almost slight compared to her own psychic ones. Listen to the recordings of the interviews that led to the book, done in Paris in 1982they are available at the Hoover Institution Archives, in Stanford, Californiaand you will hear a disembodied tumble of words made substantial by anger and defiance, muted, perhaps numbed, by repetition, from having already told her story so many times to sympathizers, strangers, and reporters in an effort to raise awareness about what was happening in Guatemala. In one interview she did in the Montparnasse apartment of Arturo Taracena, a member of the insurgent Ejrcito Guerrillero de los Pobres (EGP) then working on his doctorate in history, Mench recounts what she called la vida mala of peasants: we are machines of production... always producing, never receiving. This isnt just my pain, she says, with the bells of the glise Saint-Pierre-de-Montrouge tolling faintly in the background, but the pain of a whole people.

The introduction I wrote was not published in the new edition. Neither I nor Verso were aware that Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, the anthropologist and journalist who conducted most of the interview with Mench, had the power, based on the original 1982 contract she signed with the French publisher, ditions Gallimard, to approve or reject future editions and additional material that might be added to the English version of the book published

All of the above occurred in the early 1990s, a full half decade before Stolls expos kicked off a firestorm of criticism against Mench. In all of the ink spilt about that controversy, all of the accusations leveled against Mench, not one reporter, as far as I know, thought it worth mentioning that the book, whatever its intellectual and political provenance, did not legally belong to Mench. Im not especially politically correct, and have always thought that defenses of Menchs memoir based on her positionthat is, as an indigenous woman with claims to ways of knowing or speaking distinct from colonial knowledgecame up short. Yet this particular arrangement, whereby Mench got the opprobrium but not the royalties her book generated, does seem unjust. And it perhaps accounts for her conflictive relationship to her own memoir. Faced with unrelenting, and often unfounded, criticismdiscussed in more detail in the essay that followsand cut off from its proceeds, Mench has distanced herself from the book. She has moved on, continuing her work on the international stage as an advocate of indigenous rights and trying to launch a political career in Guatemala.

This is a shame, for the integrity of the memoir, both as a political and historical document, remains intact. Stoll has repeatedly justified his expos by arguing that the popularity of I, Rigoberta Mench built support outside of Guatemala that the insurgents had lost inside of the country, prolonging a war that would have ended much earlier, which only brought more misery to the people, in whose name the guerrillas fought. This is simplistic and wrong. The political success of the book, its unexpected wild popularity in Europe and the US, actually strengthened the non-militarist wing of the insurgents, which was able to use the attention the book focused on Guatemala to create a political space that allowed for a negotiated end to the countrys prolonged civil war. I, Rigoberta Mench, with its forceful promotion of indigenous identity and rights, can in many ways be considered a precursor to the formation of guerrilla-allied organizations, such as GAM and CERJ (respectively, in English, the Mutual Support Group of Relatives of the Disappeared and the Council of Ethnic Communities), which advocated on behalf of human rights and the rule of law in order to strengthen democratic institutions and compel the state and the military to the bargaining table.

And breezy repudiations by New Yorks literati notwithstanding, Menchs work of course is not fiction. Hence this volume, which includes the introduction and also, for the first time in translation, the historical section of the United Nationsadministered truth commission, the Comisin para el Esclarecimiento Histrico (CEH), or, in English, the Historical Clarification Commission. Published in June 1999, the CEHs twelve-volume final report fully confirms Menchs interpretation of the conflict that took the lives of her brother, father, and mother. I, along with about 300 others, had worked with the commission, though had departed before its conclusions were drafted. One of the issues that dominated the commissionstaffed largely by lawyers and other human rights professionals who work the international crisis circuit, from Haiti to Kosovo, with little specific knowledge of Guatemalan history or commitment to any particular interpretation of the warwas whether or not genocide against Mayan Indians had taken place. The assault on Mayan communitiesover a hundred thousand dead, hundreds of villages, including Menchs, razedwas undeniable. But the debate was: Did the military and its allies kill Mayans because they were Mayan or because they were the real or imagined support base of the insurgents?