Lang, Andrew, THE ORANGE FAIRY BOOK. (0-486-21909-7)

Lang, Andrew, THE PINK FAIRY BOOK. (0-486-21792-2)

Lang, Andrew, THE RED FAIRY BOOK. (0-486-21673-X)

Lang, Andrew, THE VIOLET FAIRY BOOK. (0-486-21675-6)

Lear, Edward, THE COMPLETE NONSENSE OF EDWARD LEAR. (Available in U.S. only.) (0-486-20167-8)

Linderman, Frank B., INDIAN WHY STORIES. (0-486-28800-5)

Mackenzie, Donald A., SCOTTISH WONDER TALES FROM MYTH AND LEGEND. (0-486-29677-6)

MacManus, Seumas, DONEGAL FAIRY STORIES. (0-486-21971-2)

MacManus, Seumas, FAVORITE IRISH FOLK TALES. (0-486-40549-4)

Montgomery, Frances T, BILLY WHISKERS. (0-486-22345-0)

Moore, Clement C., THE NIGHT BEFORE CHRISTMAS. (0-486-22797-9)

Newell, Peter, TOPSYS AND TURVYS. (0-486-21231-9)

Pyle, Howard, THE BOOK OF PIRATES. (0-486-41304-7)

Pyle, Howard, MEN OF IRON. (0-486-42841-9)

Pyle, Howard, THE MERRY ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD. (0-486-22043-5)

Pyle, Howard, OTTO OF THE SILVER HAND. (0-486-21784-1)

Pyle, Howard, THE STORY OF THE CHAMPIONS OF THE ROUND TABLE. (0-486-21883-X)

Pyle, Howard, THE STORY OF THE GRAIL AND THE PASSING OF ARTHUR. (0-486-27361-X)

Pyle, Howard, THE STORY OF KING ARTHUR AND HIS KNIGHTS. (0-486-21445-1)

Pyle, Howard, THE STORY OF SIR LAUNCELOT AND HIS COMPANIONS. (0-486-26701-6)

Pyle, Howard, THE WONDER CLOCK OR, FOUR AND TWENTY MARVELOUS TALES. (0-486-21446-X)

Rossetti, Christina, SING-SONG. (0-486-22107-5)

Seton, Ernest Thompson, WILD ANIMALS I HAVE KNOWN. (0-486-41084-6)

Thomas, W. Jenkyn, THE WELSH FAIRY BOOK. (0-486-41711-5)

Thompson, Stith, TALES OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS. (0-486-41131-1)

Paperbound unless otherwise indicated. Available at your book dealer, online at www.doverpublications.com, or by writing to Dept. 23, Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, NY 11501. For current price information or for free catalogs (please indicate field of interest), write to Dover Publications or log on to www.doverpublications.com and see every Dover book in print. Each year Dover publishes over 500 books on fine art, music, crafts and needlework, antiques, languages, literature, childrens books, chess, cookery, nature, anthropology, science, mathematics, and other areas.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

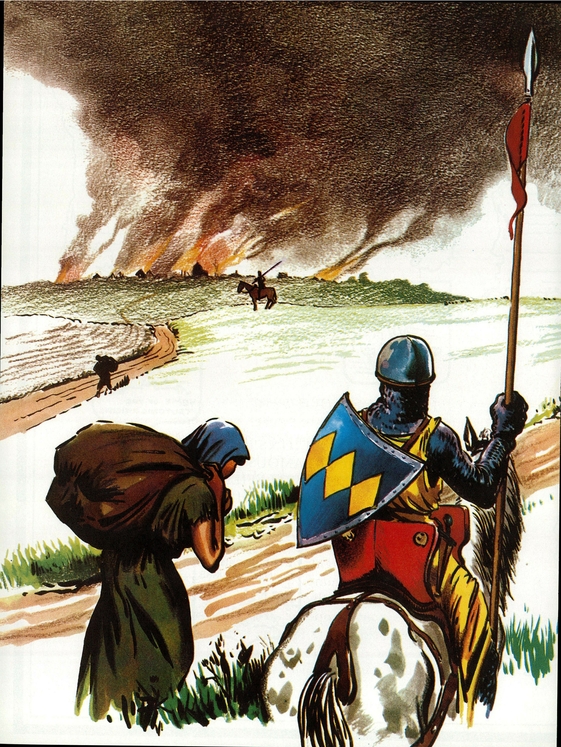

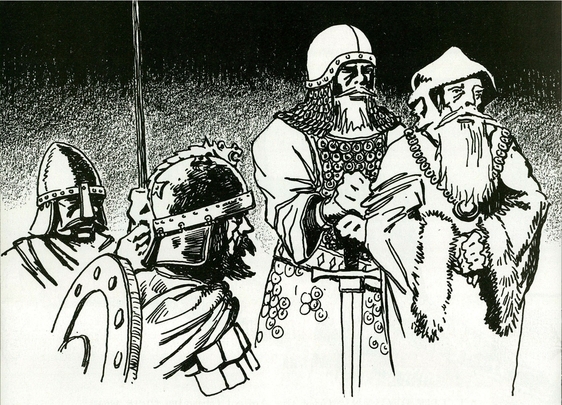

AT THE BEGINNING of the Age of Chivalry there were no organized governments. Nobles and overlords each had their own tiny kingdoms, centered around a huge stone castle. They had their knightswho were the select group of fighting men, comparable to the officers of a modern armyand the foot soldiers and archers, who were the privates.

Each noble also had his serfs, or peasants, who tilled his lands and kept his herds. In return for their work, the nobles and knights protected them. Knighthood legends grew out of this duty of the knights to protect the weak and the poor.

The nobles were almost constantly at war with each other, attacking the castles of their rivals to rob and loot, and in defense of their own properties. For this reason, the knights were trained primarily as fighting men, ready to protect the property of their lords from the frequent raids of neighboring lords and wandering bands.

AS TIME went on, groups of neighboring nobles banded together for mutual protection. The richest and strongest among themthe one who had the most knights and the largest army of foot soldiersbecame king, and the other nobles pledged their loyalty to him. But fighting continued as kingdoms went to war against each other.

At last, in the natural course of events, the various kings banded together or were conquered by their rivals, until each country had but one king. This was the beginning of organized national government and also of large-scale wars between countries, such as those that raged for a great many years between England and France.

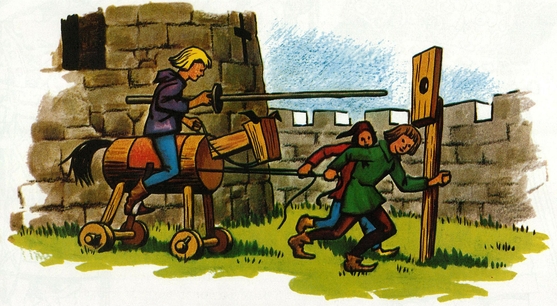

MOST KNIGHTS were the sons of kings, princes, barons and other knights. They started their training for knighthood early in life, usually about the age of seven. While they were learning, they earned their keep as pages, running errands, caring for the knights armor and waiting on table in the great hall of their masters castle. Meanwhile, they went to school. Here, instead of learning to read and write, which was not considered a proper occupation for knights, they learned to ride, to fight with wooden swords and lances, to wrestle and to run.

One of the favorite training exercises was riding at the quintain. This was a board with a hole in it, set on a stout post. One boy, carrying a wooden lance, sat on a wooden hobby horse with wheels. Other boys pulled the horse as fast as they could toward the target. If the rider was skillful, he placed the lance through the hole. If he missed, however, he was often thrown to the ground from the impact of lance against board.

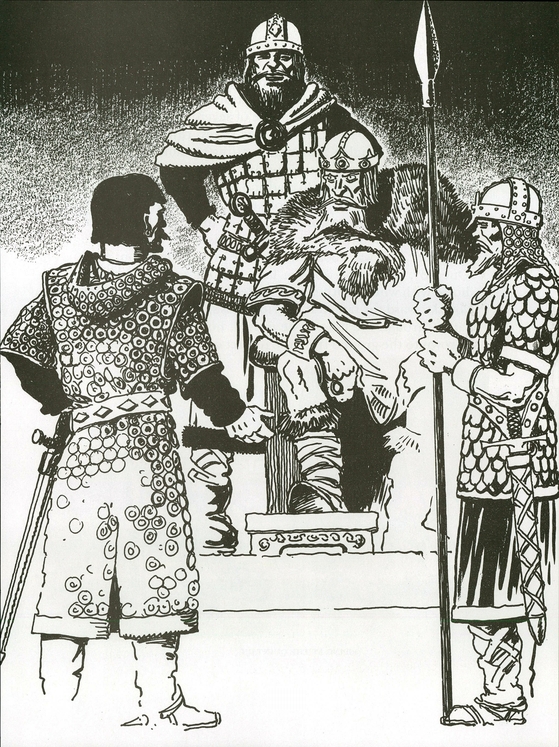

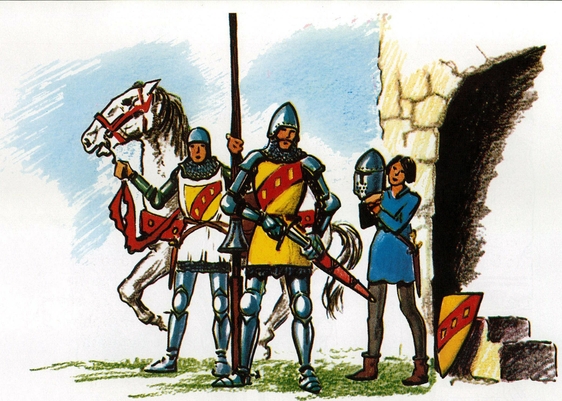

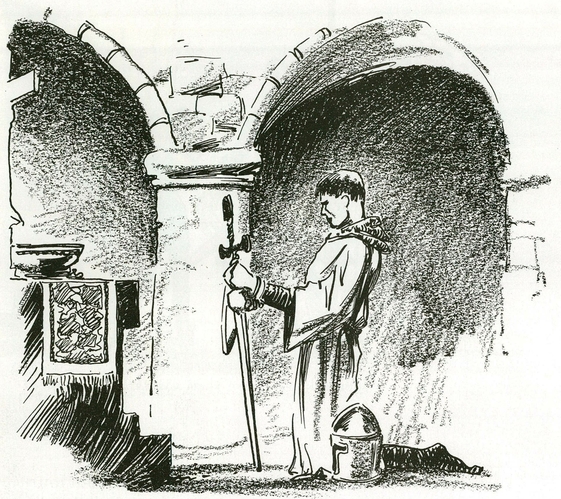

SQUIRE AND PAGE WITH THEIR MASTER

THE TRAINING of a page went on until he was about fourteen years old. Then, if his teachers were satisfied that he might someday make a good knight, he was promoted to the rank of squire. He was assigned as the personal servant to a knight, caring for his masters armor, his war horse and his weapons. And now, instead of a wooden sword, he carried a real one with which he practiced every day.

The knights took great pride in the progress made by their squires, and taught them all they knew about the art of warfare. Sometimes, in battle, the squires formed a second line of defense behind the knights.

When a squire reached the age of twenty-one, he was ready to become a knight. But before he could win his spurs, which was a symbol of knighthood, he had to prove himself by some feat of bravery or skill at arms.