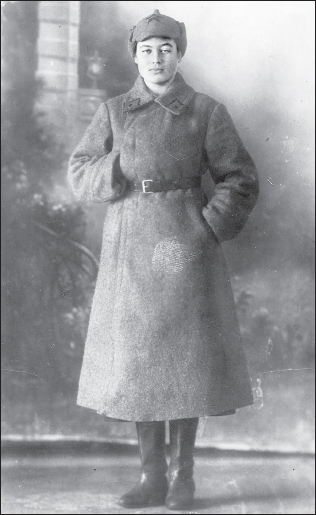

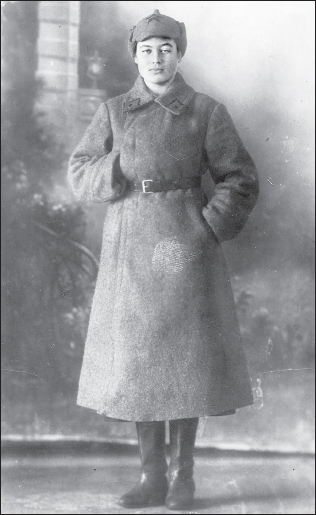

My mother during the Soviet-Finnish War, 1939

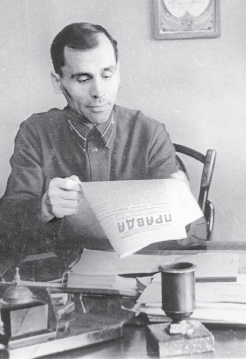

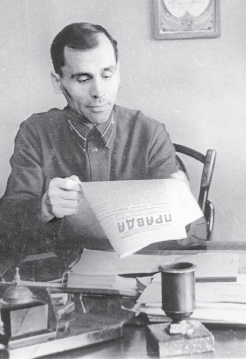

My father during the Great Patriotic War (World War II) reading Pravda, 1943

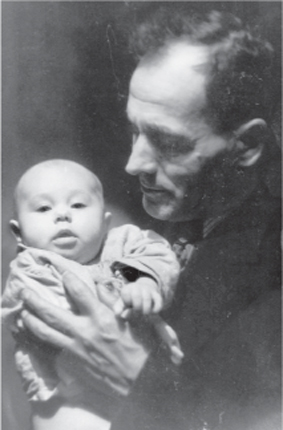

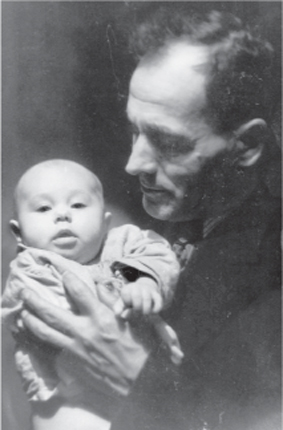

My father after my birth, 1955

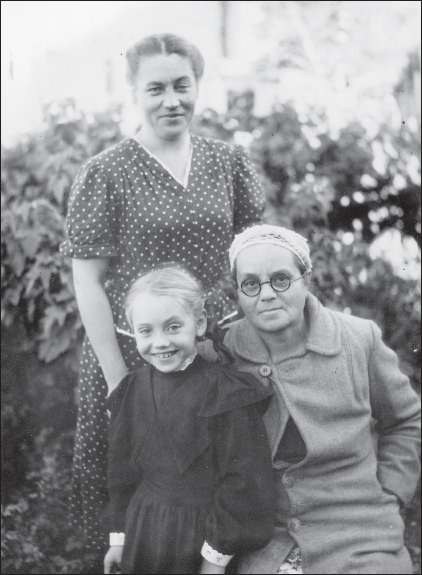

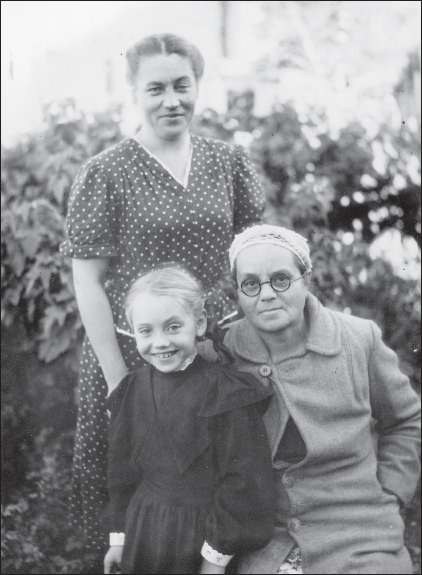

My grandmother, my mother, and Marina, 1950, Ivanovo

Lunch at my Leningrad nursery school (I am second from the right), 1959

Third grade: Vera Pavlovna in the center; Dimka the hooligan next to her on the left, second row; Zoya the diamond in the last row, second from right; I am in the third row, fifth from left, 1965

With my grandmother and grandfather at the dacha, 1964

Lunch in our dacha veranda, early 1960s. From left: my cousin Kostya, my grandfather and grandmother, Aunt Muza, my mother and father

Doing garden work in front of the dacha veranda, 1968

Marina (center) in her first film role: Dunyasha in Rimsky-Korsakovs The Tsars Bride, 1963

My mother (first row, center) with her students at a dissection class, late 1960s

Visiting my mother in Leningrad after I had been in the U.S. for five years, 1985

My mother and Marina in New Orleans, 1998

With my daughter in Nutley, New Jersey, 1989

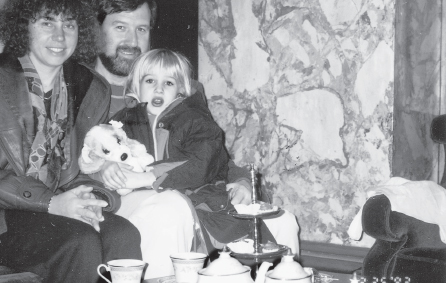

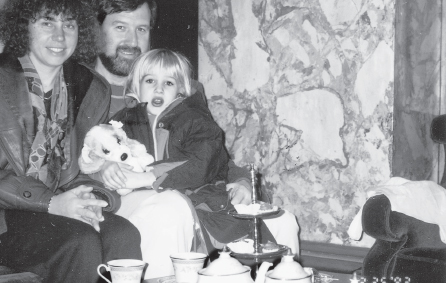

With my husband and daughter on a trip to San Francisco, 1993

Acknowledgments

I AM DEEPLY GRATEFUL TO my agent, Molly Friedrich, extraordinary in every way, for taking a chance on this first memoir and for guiding me ever since; to my editor, Priscilla Painton, for her insight, grace, and sharp eye; and to Jacobia Dahm, my reader who first called it a book. My gratitude also goes to Victoria Meyer, executive director of publicity at Simon & Schuster, for her enthusiasm about the book, and to Loretta Denner, for her exactitude and style. Lucy Carson, Michael Szczerban, and Dan Cabrera, thank you for your support.

The inspiration for this memoir came from Frank McCourts seminar at the Southampton Writers Conference, where the intelligence and energy of my exceptional classmates challenged expectations and created magic. I have learned from the conferences many mentors and friends, and I am grateful for their wisdom and gracious advice. My special thanks to Robert Reeves, the conference director, and Jody Donohue, a poet and a friend.

I am thankful to my fellow writers Pearl Solomon, Patricia Hackbarth, and Ruth Hamel, whose suggestions have improved many chapters; to Nadia Carey, an old friend from Leningrad, for setting some facts straight; and to Eleanor Oakley for her enormous heart.

My appreciation goes to Donna Perreault of The Southern Review, Stephanie GSchwind of Colorado Review, Robert Stewart of New Letters, and Lou Ann Walker of the Southampton Review for publishing chapters from the memoir; and to Juris Jurjevics of Soho Press for his generous support. My gratitude to the late Staige D. Blackford of The Virginia Quarterly Review for his kind words dating back to the twentieth century, the first encouragement I received from an editor.

Spasibo to Irina Veletskaya, Anna Graham, Luba Borisova, and Olga Kapitskaya for their friendship, the Russian kind.

I thank my sister Marina for her soul filled with talent and my mother for her head filled with memories. Also, I am indebted to my remaining family in Russia, although they would have probably told a different story of our past.

And finally, this book would not be possible without the two closest people: Laurenka, who may have been touched by Russia more than she knows, and Andy, my most ardent advocate, exacting reader, and unwavering supporter since my first years in this country, when the English language was still a mystery. To you, my love.

1. Ivanovo

I WISH MY MOTHER HAD come from Leningrad, from the world of Pushkin and the tsars, of granite embankments and lace ironwork, of pearly domes buttressing the low sky. Leningrads sophistication would have infected her the moment she drew her first breath, and all the curved faades and stately bridges, marinated for more than two centuries in the citys wet, salty air, would have left a permanent mark of refinement on her soul.

But she didnt. She came from the provincial town of Ivanovo in central Russia, where chickens lived in the kitchen and a pig squatted under the stairs, where streets were unpaved and houses made from wood. She came from where they lick plates.

Born three years before Russia turned into the Soviet Union, my mother became a mirror image of my motherland: overbearing, protective, difficult to leave. Our house was the seat of the politburo, my mother its permanent chairman. She presided in our kitchen over a pot of borsch, a ladle in her hand, ordering us to eat in the same voice that made her anatomy students quiver. A survivor of the famine, Stalins terror, and the Great Patriotic War, she controlled and protected, ferociously. What had happened to her was not going to happen to us. She sheltered us from dangers, experience, and life itself by a tight embrace that left us innocent and gasping for air.

She commandeered trips to our crumbling dachaunder the Baltic clouds, spitting rainto plant, weed, pick, and preserve for the winter whatever grew under the rare sun that never rose above the neighbors pigsty. During brief northern summers we sloshed through a swamp to the shallow waters of the Gulf of Finland, warm and yellow as weak tea; we scooped mushrooms out of the forest moss and hung them on thread over the stove to dry for the winter. My mother planned, directed, and took charge, lugging buckets of water to beds of cucumbers and dill, elbowing in lines for sugar to preserve the fruit wed need to treat winter colds. When September came, we were back in the city, rooting in the cupboard for gooseberry jam to cure my cough or black currant syrup to lower my fathers blood pressure. We were back to the presidium speeches and winter coats padded with wool and preparations for more April digging.

Next page