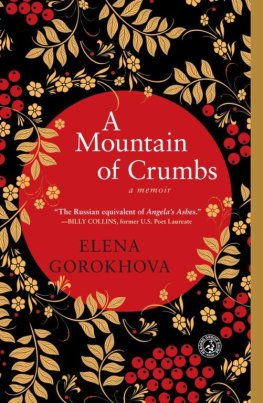

Also by Elena Gorokhova

A Mountain of Crumbs

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.simonandschuster.com

Copyright 2015 by Elena Gorokhova

Certain names and identifying characteristics have been changed, some people are composites, and certain events have been reordered and/or compressed.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition January 2015

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Aline C. Pace

Jacket design by Catherine Casalino

Jacket art from Russian Textiles: Printed Cloth for the Bazaars of Central Asia, by Susan Meller. Abrams, New York, 2007. Photograph by Don Tuttle.

Author photo Lauren Perlstein

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gorokhova, Elena.

Russian tattoo : a memoir / Elena Gorokhova.

pages cm

1. Gorokhova, Elena. 2. Gorokhova, ElenaFamily. 3. Russian AmericansBiography. 4. RussiansUnited StatesBiography. 5. ImmigrantsUnited StatesBiography. 6. WomenUnited StatesBiography. 7. Mothers and daughtersUnited States. 8. Intergenerational relationsUnited States.

I. Gorokhova, Elena. Mountain of crumbs. II. Title.

E184.R9G67 2015

305.8917'1073092dc23

[B]

2014014583

ISBN 978-1-4516-8982-2

ISBN 978-1-4516-8984-6 (ebook)

For Andy and Laurenka

Cut yourself free of what you love and hope that the wound heals.

J. M. C OETZEE , S UMMERTIME

P ART 1

Robert

One

I wish I could clear my mind and focus on my imminent American future. I am twelve kilometers up in the airforty thousand feet, according to the new, nonmetric system I have yet to learn. Every time I glance at the overhead television screen that shows the position of my Aeroflot flight, this future is getting closer. The miniature airplane is like a needle over the Atlantic, stitching the two hemispheres together with the thread of our route. I wish I could get ready and dredge my mind of all the silt of my previous life. But I cant. I cant help but think of my mothers crumpled face back in Leningrad airport, of her gaze, open, like a fresh wound, of her smells of the apple jam from our dacha mixed with the sharp odor of formaldehyde shed brought home from the medical school where she teaches anatomy. I cant help but think of my sister Marinas tight embrace and her hair the color of apricots, one fruit that failed to grow in our dacha garden my grandfather planted. Ten hours earlier, I said good-bye to both of them.

In my Leningrad courtyard, where a taxi was waiting to take us to the airport, a small girl with braids had crouched on the ledge of a sandbox: green eyes, slightly slanted, betraying the drop of Tatar ancestry in every Russian; faint freckles, as if someone had splashed muddy water onto her skin. As the plane taxied past evergreen forests and riveted itself into the low Russian sky, I longed to be that girl, not ready to leave, still comfortable on the ledge of her childhood sandbox.

When I am not watching the plane advance westward on the screen, I talk to my neighbor, a morose-looking American with thin-rimmed glasses and a plastic cup of vodka in his hand. He has just warned me, between sips of Stolichnaya, that I will never find a teaching job in the United States. He is a former professor of Russian literature, bitter and disillusioned, and, as we glide over Greenland, he dismisses my approaching American future with a single wave of his hand. You should go back home, he says, staring into his glass and rattling the ice cubes. Its 1980, and what youre looking for in the U.S. no longer exists. Youll be happier with your family in Russia.

My family in Russia would applaud this statementespecially my mother, who thinks Ill be begging on the streets and sleeping under a bridge, as Pravda has informed her.

I know I should tell this Russian expert that my new American husband is waiting for me at the airport, probably with a list of teaching jobs in his pocket. I should tell him to mind his own business. I should tell him that no one in Russia puts ice in drinks or ever sips vodka. But I dont. I am a docile exYoung Pioneer who only this morning left the Soviet Union, a ravaged suitcase on the KGB inspectors table with twenty kilograms of what used to be my life.

In the sterile maze of Washington Dulles International Airport, an official pulls me into a little room, tells me to sit down, and points a camera at my face. A flash goes off and I blink. Another man in uniform dips my index finger in ink and presses it to paper. Sign and date here. He points to a line, and I write my name and the date, August 10, 1980. Here is your green card, he says and hands me a small rectangular piece of plastic. I dont know why he calls it a green card. It is white, with a fingerprint in the middle to certify that the bewildered face is mine.

I feel as if I were inside an aquarium, sensing everything through layers of water, clear and still and deeper than I know, with real life happening to other people behind the glass. They are pulling suitcases that roll magically behind them; they are waiting for their flights in docile, passive linesall without color or sound, like a silent film. With a new identity bestowed on me by the card between my fingers, I float out of the immigration office, the weight of my suitcase strangely diminished, as though the value of my Russian possessions has instantly shrunk with the strike of the immigration stamp. The sign in front of me points an arrow to something called restroom , although I can see it is not going to dispense any rest. The floor gleams here, the hand dryers whir, and the faucets sparkle restroom is a perfect word for this luxury that seems to have emerged straight from the spotless future of science fiction. I think of the rusty toilets of Pulkovo International Airport I just left, of their corroded pipes and sad, hanging pull chains that never release enough water to wash away the lowly feeling of barely being human.

In the waiting crowd I make out Robert, my new American husband, a man I barely know. He is peering in my direction through his thick glasses, not yet able to see me among the exiting passengers. It feels odd to apply the word husband to a tall stranger in corduroy jeans and tight springs of black hair around his waiting face. And what about me? Do I want to be a wife, the word that in Russia mostly conjures standing: on lines, at bus stops, by the stove?

Five months earlier, Robert came to Leningrad to marry me, to my mothers horror. We stood in the wedding hall of the Acts of Marriage Palace on the Neva embankmenta small flock of my mortified relatives and close friendsin front of a woman in a red dress with a wide red ribbon across her chest, who recited a speech about the creation of a new society cell. The speech was modified for international marriages: there was no reference to our future contributions to the Soviet cause or to the bright dawn of communism.

To be honest, the possibility of leaving Russia was never as thrilling as the prospect of leaving my mother. My mother, a mirror image of my Motherlandoverbearing and protective, controlling and nurturinghad spun a tangle of conflicted feelings as interlaced as the nerves and muscles in her anatomy charts Id copied since I was eight. Our apartment on Maklina Prospekt was the seat of the politburo; my mother, its permanent chairman. She presided in our kitchen over a pot of borsch, ordering me to eat in the same voice that made her anatomy students quiver. She sheltered me from dangers, experience, and life itself by an embrace so tight that it left me innocent and gasping for air and that sent me fumbling through the first ordeals of adulthood. She had survived the famine, Stalins terror, and the Great Patriotic War, and she controlled and protected, ferociously. What had happened to her was not going to happen to Marina and me.

Next page