Vladimir Nabokov - Speak, Memory

Here you can read online Vladimir Nabokov - Speak, Memory full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2011, publisher: Vintage International, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Speak, Memory

- Author:

- Publisher:Vintage International

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- City:New York

- ISBN:978-0-307-78773-6

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Speak, Memory: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Speak, Memory" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Speak, Memory — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Speak, Memory" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Vladimir Nabokov

SPEAK, MEMORY

An Autobiography Revisited

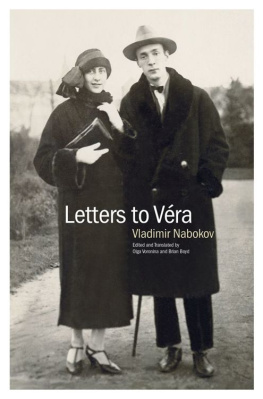

To Vra

Foreword

THE present work is a systematically correlated assemblage of personal recollections ranging geographically from St. Petersburg to St. Nazaire, and covering thirty-seven years, from August 1903 to May 1940, with only a few sallies into later space-time. The essay that initiated the series corresponds to what is now Chapter Five. I wrote it in French, under the title of Mademoiselle O, thirty years ago in Paris, where Jean Paulhan published it in the second issue of Mesures, 1936. A photograph (published recently in Gisle Freunds James Joyce in Paris) commemorates this event, except that I am wrongly identified (in the Mesures group relaxing around a garden table of stone) as Audiberti.

In America, whither I migrated on May 28, 1940, Mademoiselle O was translated by the late Hilda Ward into English, revised by me, and published by Edward Weeks in the January, 1943, issue of The Atlantic Monthly (which was also the first magazine to print my stories written in America). My association with The New Yorker had begun (through Edmund Wilson) with a short poem in April 1942, followed by other fugitive pieces; but my first prose composition appeared there only on January 3, 1948: this was Portrait of My Uncle ( (Gardens and Parks, June 17, 1950), all written in Ithaca, N.Y.

Of the remaining three chapters, Chapters went to Harpers Magazine (Lodgings in Trinity Lane, January, 1951).

The English version of Mademoiselle O has been republished in Nine Stories (New Directions, 1947), and Nabokovs Dozen (Doubleday, 1958; Heinemann, 1959; Popular Library, 1959; and Penguin Books, 1960); in the latter collection, I also included First Love, which became the darling of anthologists.

Although I had been composing these chapters in the erratic sequence reflected by the dates of first publication given above, they had been neatly filling numbered gaps in my mind which followed the present order of chapters. That order had been established in 1936, at the placing of the cornerstone which already held in its hidden hollow various maps, timetables, a collection of matchboxes, a chip of ruby glass, and evenas I now realizethe view from my balcony of Geneva lake, of its ripples and glades of light, black-dotted today, at teatime, with coots and tufted ducks. I had no trouble therefore in assembling a volume which Harper & Bros. of New York brought out in 1951, under the title Conclusive Evidence; conclusive evidence of my having existed. Unfortunately, the phrase suggested a mystery story, and I planned to entitle the British edition Speak, Mnemosyne but was told that little old ladies would not want to ask for a book whose title they could not pronounce. I also toyed with The Anthemion which is the name of a honeysuckle ornament, consisting of elaborate interlacements and expanding clusters, but nobody liked it; so we finally settled for Speak, Memory (Gollancz, 1951, and The Universal Library, N.Y., 1960). Its translations are: Russian, by the author (Drugie Berega, The Chekhov Publishing House, N.Y., 1954), French, by Yvonne Davet (Autres Rivages, Gallimard, 1961), Italian, by Bruno Oddera (Parla, Ricordo, Mondadori, 1962), Spanish, by Jaime Pieiro Gonzles (Habla, memoria!, 1963) and German, by Dieter E. Zimmer (Rowohlt, 1964). This exhausts the necessary amount of bibliographic information, which jittery critics who were annoyed by the note at the end of Nabokovs Dozen will be, I hope, hypnotized into accepting at the beginning of the present work.

While writing the first version in America I was handicapped by an almost complete lack of data in regard to family history, and, consequently, by the impossibility of checking my memory when I felt it might be at fault. My fathers biography has been amplified now, and revised. Numerous other revisions and additions have been made, especially in the earlier chapters. Certain tight parentheses have been opened and allowed to spill their still active contents. Or else an object, which had been a mere dummy chosen at random and of no factual significance in the account of an important event, kept bothering me every time I reread that passage in the course of correcting the proofs of various editions, until finally I made a great effort, and the arbitrary spectacles (which Mnemosyne must have needed more than anybody else) were metamorphosed into a clearly recalled oystershell-shaped cigarette case, gleaming in the wet grass at the foot of an aspen on the Chemin du Pendu, where I found on that June day in 1907 a hawkmoth rarely met with so far west, and where a quarter of a century earlier, my father had netted a Peacock butterfly very scarce in our northern woodlands.

In the summer of 1953, at a ranch near Portal, Arizona, at a rented house in Ashland, Oregon, and at various motels in the West and Midwest, I managed, between butterfly-hunting and writing Lolita and Pnin, to translate Speak, Memory, with the help of my wife, into Russian. Because of the psychological difficulty of replaying a theme elaborated in my Dar (The Gift), I omitted one entire chapter (). On the other hand, I revised many passages and tried to do something about the amnesic defects of the originalblank spots, blurry areas, domains of dimness. I discovered that sometimes, by means of intense concentration, the neutral smudge might be forced to come into beautiful focus so that the sudden view could be identified, and the anonymous servant named. For the present, final, edition of Speak, Memory I have not only introduced basic changes and copious additions into the initial English text, but have availed myself of the corrections I made while turning it into Russian. This re-Englishing of a Russian re-version of what had been an English re-telling of Russian memories in the first place, proved to be a diabolical task, but some consolation was given me by the thought that such multiple metamorphosis, familiar to butterflies, had not been tried by any human before.

Among the anomalies of a memory, whose possessor and victim should never have tried to become an autobiographer, the worst is the inclination to equate in retrospect my age with that of the century. This has led to a series of remarkably consistent chronological blunders in the first version of this book. I was born in April 1899, and naturally, during the first third of, say, 1903, was roughly three years old; but in August of that year, the sharp 3 revealed to me (as described in Perfect Past) should refer to the centurys age, not to mine, which was 4 and as square and resilient as a rubber pillow. Similarly, in the early summer of 1906the summer I began to collect butterfliesI was seven and not six as stated initially in the catastrophic second paragraph of . Mnemosyne, one must admit, has shown herself to be a very careless girl.

All dates are given in the New Style: we lagged twelve days behind the rest of the civilized world in the nineteenth century, and thirteen in the beginning of the twentieth. By the Old Style I was born on April 10, at daybreak, in the last year of the last century, and that was (if I could have been whisked across the border at once) April 22 in, say, Germany; but since all my birthdays were celebrated, with diminishing pomp, in the twentieth century, everybody, including myself, upon being shifted by revolution and expatriation from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian, used to add thirteen, instead of twelve days to the 10th of April. The error is serious. What is to be done? I find April 23 under birth date in my most recent passport, which is also the birth date of Shakespeare, my nephew Vladimir Sikorski, Shirley Temple and Hazel Brown (who, moreover, shares my passport). This, then, is the problem. Calculatory ineptitude prevents me from trying to solve it.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Speak, Memory»

Look at similar books to Speak, Memory. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Speak, Memory and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.