PRAISE FOR

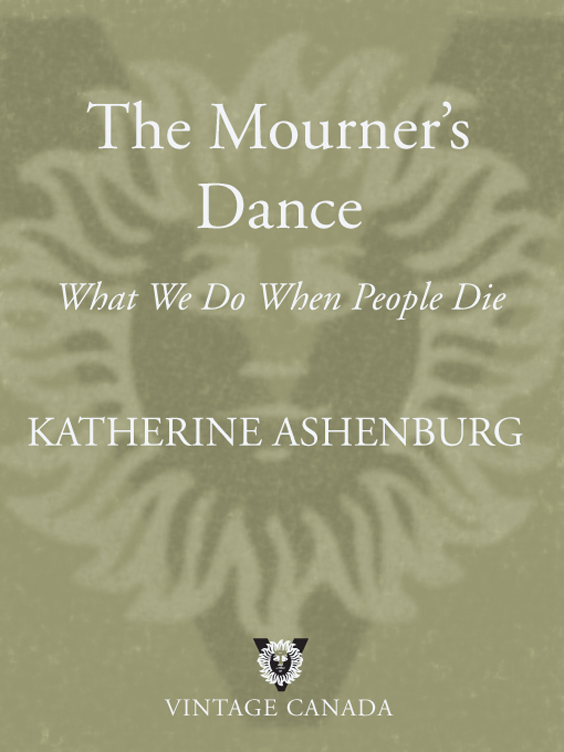

T HE M OURNERS D ANCE

A Globe and Mail Best Book

[The Mourners Dance is] a wide-ranging exploration that moves from the rawly personal to the stuff of global sociology.

Toronto Star

Death comes to everyone and the survivors go on living. How we cope goes straight to the heart of being human. The Mourners Dance learned, often moving and even consoling is a superb survey of something modernity would like to forget.

Macleans

Into her loving and intimate account of her own familys grief, Ashenburg weaves descriptions of mourning rituals from a broad range of traditions The book eloquently makes the point that mourning is a necessary and transformative experience.

Publishers Weekly

The buoyant narrative is moving, exotic, outrageous and, as in the authors own view, a potent, intensely human brew.

The Globe and Mail

The Mourners Dance is a welcome read for those of us living in a society whose normal reaction to prolonged mourning is a brisk Get over it and get on with it.

Quill & Quire

An informative, educational and entertaining text dealing with the history of how people have dealt with death through the ages.

Library Journal

Throughout the book, her daughters bereavement is never far from Ashenburgs thoughts These personal reflections establish an intimacy. As Ashenburg divulges various aspects of her daughters experience, many readers will recognize themselves Written in a crisp, eloquent style, The Mourners Dance synthesizes the universal and the personal in an effort to come to terms with grief and all its ramifications.

The Winnipeg Free Press

Ashenburg does such an admirable job of compiling variations on mourning that the reader will be struck by both the exotic and the mundane in this very human activity. The most compelling passages, however, detail the authors own grief as she, her family and her friends dealt with the death of her daughters fianc.

Psychology Today

Ashenburg intertwines the story of her familys grief with discussions of mourning rituals from different eras and cultures She reminds us that these rituals were conceived to bring comfort and to gently steer the mourner back into the world of the living. While not intended to be a self-help book, readers who have undergone the death of a loved one might find solace and wisdom in the collective human experience of loss The Mourners Dance illuminates.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

for

Sybil and Hannah

and in memory of

Scott Roche

19731998

C ONTENTS

P ROLOGUE

D uring the Christmas holidays of 1997, my two daughters and I went on a long-planned trip to Vietnam. Hannah, my younger daughter, had just become engaged, and she wore a bright sapphire and diamond ring. Talk of the wedding and Hannahs future threaded in and around our travels. Fingering Vietnamese silk in tiny shops, we imagined her dress. We planned menus and counted guests. I remember joking in Hue, as we walked through the splendid tomb garden of a Vietnamese king, that this would be a fine spot for a wedding reception.

In early January, Hannah returned to medical school in Vancouver, and her sister, Sybil, went back to her job in Hong Kong. I stayed in Asia for an additional week. Returning to my hotel one furiously wet night in Shanghai, I found an urgent message from Hannah. Scott, her fianc, had been in a car accident outside Seattle on his way to a skiing excursion. He had spinal cord damage; if he ever regained consciousness, he would be a quadriplegic. When I arrived at the Hong Kong airport the next morning, on my way to Seattle, Sybil met me with the news that Scott was going to die.

Like many Westerners at the turn of the 21st century, my family and I had not had much to do with death. In their twenties, my daughters had four living grandparents. Hannah had been to only two funerals in her life. My grandparents, aunts, and uncles had been buried after long lives, with minimal formality. This was our first experience with sudden death at a young age.

Scott died on January 10, about an hour after I reached the hospital. He had never regained consciousness. His funeral was held three days later, in the beautiful modern embrace of the Chapel of St. Ignatius at Seattle University, the place where Scott and Hannah had wanted to be married. In many ways, the funeral was a harrowing parody of what would have been their wedding. Hannah was almost always surrounded by Sybil and her three college roommates, who would have been her bridesmaids. More than two hundred friends and family crowded the chapel. Hannahs ring glinted on the lectern as she reminisced about Scott and their six years together. Scotts mother spoke too, and his brother Stephan, who was to have been his best man. Afterward, there was a luncheon for everyone at a restaurant, with an open microphone. Dozens of young people walked up to tell funny stories about Scott. It was dreadful, and ineffably comforting.

Once the funeral was over and family and friends dispersed, I assumed that custom and ceremony had had their day. Now we would be left to mourn in the modern way utterly privately and spontaneously, in an unscheduled and mostly unmarked grief, unconstrained by repetition or expectation. This was so obvious that it never occurred to me to think of it as a deprivation. But I reckoned without Hannah.

I used to tease Hannah by telling her that when it came to much of Western civilization, she was an intelligent stranger. What I meant was that she preferred playing the piano or talking with friends to reading. A student of music and science, she had little interest in history. She had finished very few Victorian novels. And yet, in the weeks after Scotts death, something began to impress itself on me. All by herself, as if instinctively, she was designing practices that more traditional cultures had institutionalized as part of their mourning process. Some of her handmade customs involved Scotts belongings or mementoes of him. Others involved carving out times and places in which to remember Scott in a particular, recurring way. Just as older societies paid close attention to the mourners retreat from society, Hannah wrote the rules for her own balance of seclusion and company.

In the midst of sadness and worry for her, I wondered about the source of her observances. Other than a few time-honored holiday customs, we are not especially rich in ritual as a family. True, Hannahs childhood had included the sacraments and ceremonies of the Catholic Church. Although she seemed to have left that part of her life without much lingering connection, perhaps those modernized and rather diluted rituals had left some trace.

Traditional mourning customs almost always involve a timeline, a date when the widow moves from black to grey clothes, when Kaddish no longer needs to be said daily, when a party may be attended. Hannah too had at least one date in her mind. A month or so after Scotts death, I had a dream that she moved her engagement ring from her left hand to her right. Telling her about the dream, I finished almost apologetically, I guess that was a bit premature. She said immediately, Im thinking about September 6. Their wedding had been scheduled for September 5. She had already decided to wear her ring on her left hand for the full period of her engagement, then move it. I remember thinking that the Victorians, those expert mourners about whom Hannah knew almost nothing, would approve of this girl.