BOOKS BY ANITA DIAMANT

FICTION

The Boston Girl

Day After Night

The Last Days of Dogtown

Good Harbor

The Red Tent

NONFICTION

Pitching My Tent

The Jewish Wedding Now

How to Raise a Jewish Child

Saying Kaddish:

How to Comfort the Dying, Bury the Dead, and Mourn as a Jew

Choosing a Jewish Life:

A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends

Bible Baby Names:

Spiritual Choices from Judeo-Christian Tradition

The New Jewish Baby Book:

Names, Ceremonies, and Customsa Guide for Todays Families

Living a Jewish Life:

Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Todays Families

Copyright 1998, 2019 by Anita Diamant

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Schocken Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 1998.

Schocken Books and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Permissions acknowledgments appear on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Diamant, Anita.

Saying Kaddish : how to comfort the dying, bury the dead, and mourn as a Jew / Anita Diamant.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8052-1088-0

1. Jewish mourning customs. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies, Jewish. 3. DeathReligious aspectsJudaism. 4. Kaddish. 5. JudaismLiturgy. 6. Consolation (Judaism) I. Title.

BM712.D53 1998

296.445dc21 98-16646

CIP

Ebook ISBN9780805212181

www.penguinrandomhouse.com

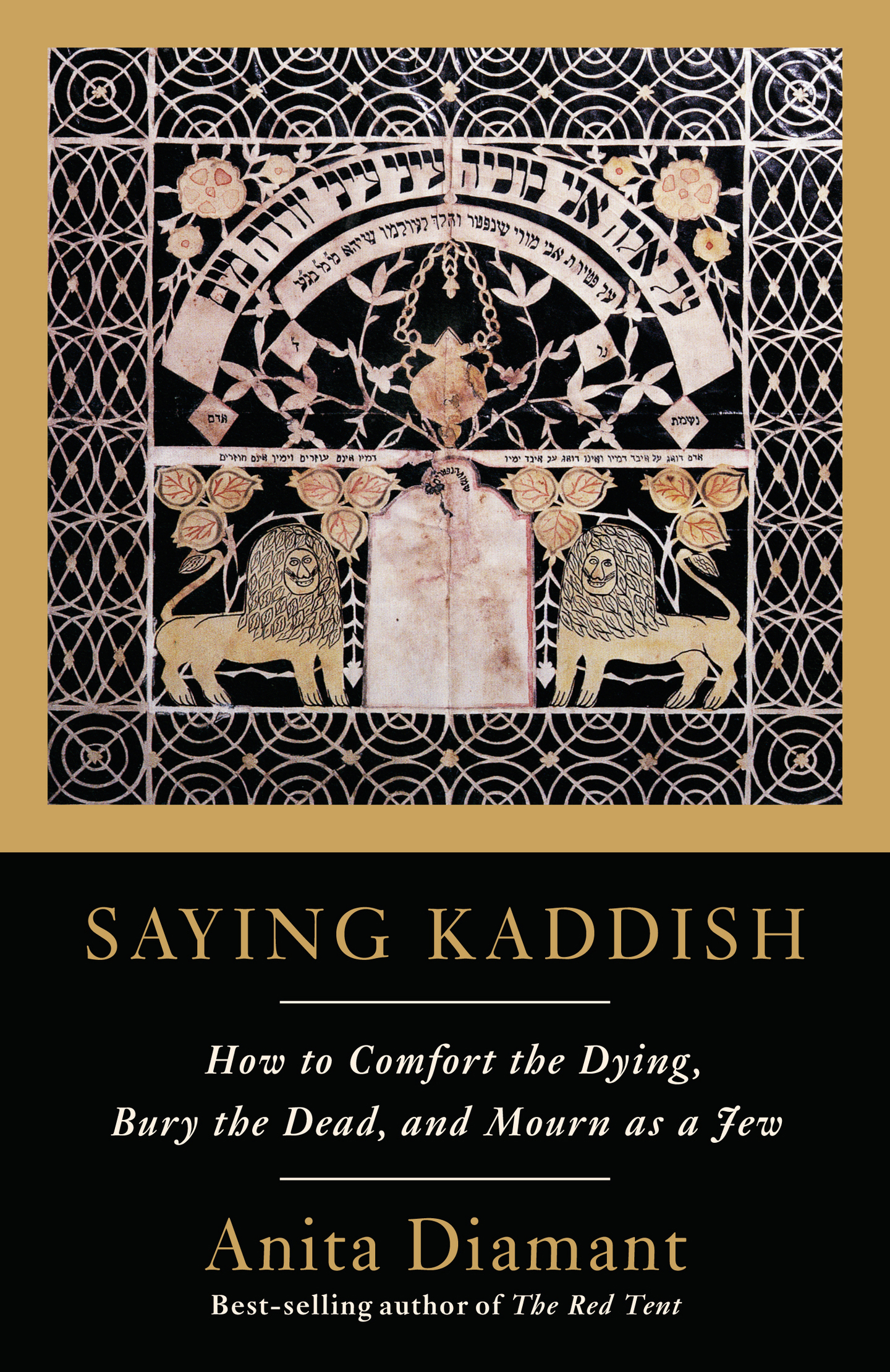

Cover image: Nineteenth-century Yahrzeit papercut by Tzvi Avigdor Palkovits, Jewish Museum, Preov, Slovakia

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v5.4

a

For my brother

Harry Diamant

A BLESSING FOR MOURNERS

My brothers and sisters who are worn out and crushed by this mourning, let your hearts consider this:

This is the path that has existed from the time of creation and will exist forever. Many have drunk from it and many will yet drink. As was the first meal so shall be the last.

My brothers and sisters, may the One who comforts comfort you.

Blessed is the One who comforts the mourners.

A BLESSING FOR CONSOLERS

My brothers and sisters who perform acts of loving-kindness, children of those who perform acts of loving-kindness:

My brothers and sisters, may the One Who rewards goodness reward you.

Blessed is the One Who rewards deeds of goodness.

Contents

Preface

I BEGAN WRITING THIS BOOK during the second year following my fathers death in 1995, with the memory of his loss and the experience of sitting shiva and saying Kaddish still present in my mind and heart.

Maurice Diamant was seventy-two when he died. It was a good death, free of suffering or fear. He had made his wishes known and said his goodbyes to friends and familyincluding me. Yet even though I knew it was coming, the shock of his death was staggering. The world I had known was gone. I would never be the same. A friend who lived above the San Andreas Fault described the feeling as a private earthquake.

During the days and weeks after my father died, I explored the quiet devastation of his loss. I assumed the role of mourner, but as lonely as the world was without my father, I was not alone. My family and my community comforted me, and I found myself traveling down a path made smooth by centuries of Jewish mourners.

I decided to stay home for the first week to sit shiva, which allowedactually, forcedme to experience the overwhelming first stage of grief and the meaning of the word consolation. Friends, neighbors, and members of my synagogue came to the door, carrying food. I was hugged and kissed and cared for in the most elemental ways. My rabbi sat with me at the kitchen table one quiet afternoon. I reminisced about my father; my rabbi described the trajectory of mourning.

I remember very little of what people said to me during shiva. But the sounds of their voices, their presence in my home, and the cards and notes that arrived in the mail were meaningful beyond measure. Grief weighed heavily, but others held me up.

Members of my congregation led a brief prayer service in the evening. Before we recited the final prayer, the Mourners Kaddish, my husband and I shared memories of my father. My then-nine-year-old daughter read a poem she had written about him. Friends recalled conversations theyd had with him and, after a few minutes, people who had never met my dad knew that he loved a joke and passionate conversation; that he was an eternal optimist; and that despite his own life experience, he never lost his faith in humanity.

Then we said Kaddish: Yit-ga-dal veyit-ka-dash shmei ra-ba.

I knew the words by heart from synagogue services, but what had been familiareven rotenow became a mantra of sadness and longing, a personal petition for peace, an extended amen to another exhausting day.

In addition to notes and cards, the mail brought news of donations to causes that reflected my fathers values. There were contributions to the library at his temple and to the memorial garden at mine; there were gifts to Amnesty International and organizations that support non-Jews who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. I continue to give charitytzedakahin his memory. I always will.

My fathers death taught me the meaning of the word blessing. His memoryeven decades lateris a reminder to be kind, to laugh, to appreciate nature and music and friendship.

My mother, Helene Diamant, died twenty-two years after my father. She was ninety-two but in good health, and her death was sudden and unexpected. I was grateful that she died without suffering or the loss of her independencean idea she found intolerable.

This time I was more familiar with the path ahead of me, and the shock was mitigated by the span of her years. Even so, I was no less touched by and grateful for the loving support of friends and acquaintances from every corner of my life and hers. Generous gifts were given in her memory, and the cards and letters were full of tenderness and affection. Again, I was surrounded by love and deeply grateful for the community that supported me during shiva and held me close during the disorientation I felt in the months that followed. As I took up the familiar consolations of Kaddish, candles, and tzedakah in her memory, I took pleasure in finding homes for her impressive collection of owls and knowing that her winter coats and boots were keeping homeless women warm through the winter.

As the first year of mourning came to a close, I resumed my lifelong study of French, which I realized later was probably an unconscious tribute to my mothers first language and a way to maintain a fond connection with her.

Why update Saying Kaddish? Certainly, there is more continuity than change in Jewish practices related to death and mourning. The enduring wisdom of our tradition helps us face death squarely and make time to feel the full range of emotionsgrief, anger, fear, guilt, reliefthat follow; accept the fact that we need other people to help bear the pain of loss; do the same for others when they lose a loved one; and take comfort from the idea that the memory of the dead is bound up in our lives and actions.