*Anything this profound philosopher ever said bears repeating. Ed.

Copyright 1974 by Frances D. Ross

Originally published in 1974 by Greyfalcon House, Inc.

Reprinted in 2015 by New Directions, by arrangement with Ann Grifalconi, Greyfalcon House

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Designed by F. D. R.

80 Eighth Avenue. New York 10011

Foreword

The first time I read Fran Rosss hilarious badass novel, Oreo, I was living on Fort Greene Place, Brooklyn in a community of people I thought of as the dreadlocked elite. It was the late 1990s, and the artisan cheese shops and organic juice bars had not yet fully arrived in the boroughs, though there were hints of what was to come. Poor people and artists could still afford to live there. We were young and black and wed moved to the neighborhood armed with graduate degrees and creative ambitions. There was a quiet storm of what Greg Tate described as black genius brewing in our midst. Spike Lee had set up a production studio inside the old firehouse on DeKalb Avenue. Around the corner on Lafayette Street was Kokobar, a black-owned espresso shop decorated with Basquiat-inspired paintings; there were whispers that Tracy Chapman and Alice Walker were investors. Around the corner on Elliot Street, Lisa Price, aka Carols Daughter, sold organic hair oils and creams for kinky-curly hair out of a brownstone storefront.

Years earlier I had read Trey Elliss seminal essay The New Black Aesthetic from my West-Coast dorm room, curled beside my dreadlocked, half-Jewish boyfriend. We saw glimmers of ourselves in his description of a new generation of black artists. We, too, had been born post-Civil Rights Movement, post-Loving, post-soul, post-everything. We were suspicious of militancy, black or otherwise, suspicious of claims to authenticity, racial and otherwise. We were culturally hybridcultural mulattos, as Ellis put itwhether we had one white parent or not.

Now, in nineties Fort Greene, we had arrived. Many of the black kids in our midst were recovering oreos: theyd grown up listening to the Clash, not Public Enemy, playing hacky sack, not basketball. They were all too accustomed toas my friend Jake Lamar once put itbeing the only black person at the dinner party.

Only now we were throwing our own dinner party. We were demi-teinthalf-tonea shade of blackness that had been formed in a clash of disparate symbols and signifiers, nothing pure about us. We were authentically nothing. Each of us had experienced a degree of alienation growing upbeing too black to be white, or too white to be black, or too mixed to be anythingand somehow at the same moment in time wed all moved into the same ten-block radius of Brooklyn together.

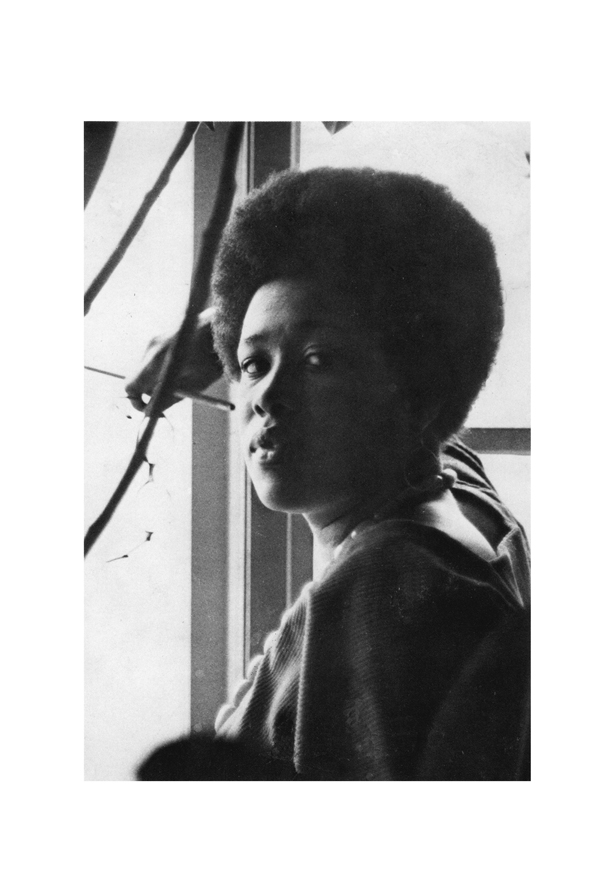

Oreo came to me in this context like a strange uncanny dream about the future that was really the past. That is, it read like a novel not from 1974 but from the near futurea book whose appearance I was still waiting for. I stared at the author photo of the woman wearing the peasant smock and her hair in an Afro and could easily imagine her moving through the streets of Fort Greene. She belonged to our world. Her blackness was our blackness.

Oreo, its first time around in 1974, had disappeared as quickly as it had appeared. It got a few amused and somewhat confused reviews in Ms. Magazine and Esquire but apparently didnt speak to the wider cultural landscape of the moment. It came out only two years before that other novel, the cultural sensation, Alex Haleys Roots: The Saga of an American Family. While Oreo may have been one of the least-known novels of the decade, Roots went on to become the single most popular novel of the decade, black or white. It occupied the number one spot on the New York Times bestseller list for twenty-two weeks. It was adapted into one of the most-watched television miniseries of all time.

For most Americans my ageparticularly if you are blackRoots is part of our childhood iconography. We can all trade stories of sitting on the family-room floor, watching with a mixture of rapture and disbelief. I remember weeping when Fiddler died, because I too played the fiddle. I remember how at school, the day after the miniseries aired, a white girl walked up to a table of black kids in the cafeteria and said, with tears in her eyes, that she was so sorry about slavery, and could she please empty their lunch trays for them?

The titles themselves of these two textsRoots and Oreoimply the profound gap between the worksgiving us a clue into the kind of black narratives we like to celebrate and the kind weve tended to ignore. Roots looks toward the past. It offers black people an origin story, an imagined moment of racial puritywhen the Mandinka warrior Kunte Kinte is kidnapped off the shores of Gambia. It constructs a lost utopia for us and a clear fall from Eden, Africa. Oreo, from the title alone and its first loony pages, suggests murkier, more polluted racial waters.

Indeed, Oreos origin story is one of gleeful miscegenation. The moment Samuel Schwartz falls for Helen (Honeychile) Clark, its too late to look back. An oreo is, of course, a cookie, white on the inside and black on the outside; it is also the taunt of choice for black people who appear to act white. Fran Ross embraces this epithet, embraces the idea of falling from racial grace. But its no mulatto sentimentalismno ebony and ivory simplistic tale of racial mushiness. From page one, both sides of Oreos familythe black and the Jewishare equally horrified by their children falling in love. In fact, James Clark, Helens father, Oreos black grandfather, is so horrified by his daughters coupling with a Jewish guy that his actual body becomes encoded by hateparalyzed into the shape of a half-swastika.

Oreo, born Christine Clark, the biracial progeny of the fall, is our heroine, and like all good heroes and heroines, shes on a quest. But unlike Alex Haley, Oreo is trying to find her white sideher missing Jewish father. Her absent father is no site of longing; hes a voice-over actor in Manhattan who has left her an absurd list of clues to help her locate him. Hes a bum, according to her mother. Im going to find that fucker, is how Oreo sets out on her search, which feels more like an excuse to wander away from her home than a real desire for a father.

Oreo is cheeky, mischievous, a tricksteror, as one uncle says of her: That girls got womb ... shes a real ball buster. She is radically, almost aggressively mixed; within one passage she can and does code-switch with ease between a multitude of tonguesfrom Yiddish to so-called Ebonics to highbrow academic jargon. Shes tainted from the get-go, a mad-cap play on Duboiss double-consciousness. Only in this case its not doubled, its tripled, quadrupled, and on. This multiplicity she inhabits is not a burden that she must fight to keep from tearing her asunder. Rather, its a source of strength and agility. Her twoness keeps her on her toes, enables her to move between multiple worlds. She is as Jewish as she is black; there is nothing tragic about this mulatto. She is, if anything, a comic mulatto, turning the world on its head with a verbal precocity and wit that sharpen her ability to shape-shift and pass.