This book is made up of material derived from private and public archives and collections, published works, unpublished works, letters, diaries, interviews, gossip, e-mails, telephone conversations, videotapes, faxes, websites and so on. Despite the fact that the subject is recent, a number of discrepancies of spelling have cropped up in proper names. Where that has happened, I have used the version most commonly used by others.

I have not tampered with usage, grammar or spelling in direct quotations from original material such as letters, though I have tidied up typographical errors for many years Peggy Guggenheim used an ancient typewriter with a faded blue ribbon, and her typing was not accurate. I have left eccentricities of spelling alone (Peggy habitually spelt thought thot, and bought bot), and have provided an explanation only if the level of obscurity seemed great enough to warrant one. Round brackets in quoted passages belong to the passage; glosses within such passages are in square brackets.

Titles of artworks in Peggys collection are generally the same as those used by Angelica Z. Rudenstine in her catalogue of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Other paintings and sculptures are given the names theyre most commonly known by.

Id like to express my thanks here at the outset to all who helped. A lot of people had a profound personal contact with Peggy, and shared their memories of her with me generously. I am most grateful to them their names are in the acknowledgements at the end of the book. I have had to be selective in the use of some tangential detail for reasons of both focus and of space. Readers interested in further exploration of the background to this book are referred to the bibliography. Inevitably what I have written will lead to a certain amount of disagreement. Some of the material conflicted, and some was clogged with gossip and rumour. I can only say that to the best of my ability I have checked all the matter I have used for correctness, and that I have tried to keep speculation to a minimum. I thank Marji Campi, Barbara Shukman and Karole Vail for looking over the manuscript, but I alone am accountable for any errors. I have not, however, consciously sought to mislead or offend anyone in this record of the life of a complex, anarchic, remarkable woman.

A Party

Her obduracy in contention and her warmth in friendship, her generosity and her stinginess, her plunges into gloom and wholehearted abandonment to laughter, her puritan streak and her reckless addiction to the erotic were all contradictions of the essence of her personality.

MAURICE CARDIFF, Friends Abroad

The rain, which had not stopped for a week, ceased in the late afternoon of 29 September 1998, so that by the evening the flagstones in the garden were dry. The heat and the humidity relented too, so that as the crowd gathered the atmosphere and the temperature were perfect.

The garden was that of the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an eighteenth-century pile in Dorsoduro, on the Accademia bank of the Grand Canal in Venice, between the Accademia Bridge and Santa Maria della Salute, close to where the Canal Grande debouches into the Canale di San Marco. The palazzo is exotic. It was never finished. It only has a sub-basement and one storey, with a flat roof that doubles as a terrace; but the garden is one of the largest in Venice. The trees are huge. When Peggy Guggenheim owned and lived in the palace, the garden was muddy and overgrown, and the sculptures planted in it the bronze trolls of Max Ernst, the minimalist, organic forms of Arp and Brancusi inhabited it as mysterious beings might lurk in a wood, waiting for the traveller to come upon them unaware.

Several hundred guests were gathering that Tuesday evening twenty years after her death in a more manicured space: neatly flagged and gravelled, with the sculptures openly displayed. Not all of the sculptures now belong to the art collection which Peggy Guggenheim brought here in the late 1940s. Many are part of the collection of the Texan collectors Patsy and Raymond Nasher.

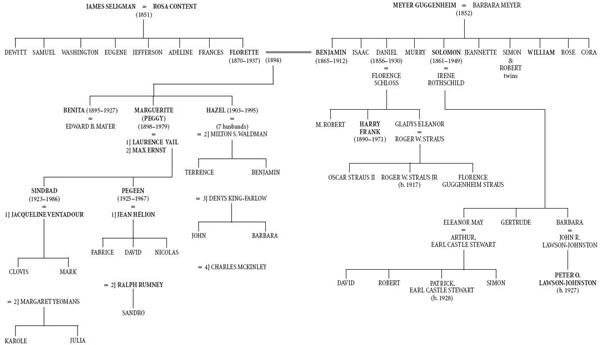

The crowd has assembled in the electrically lit, mosquito-free night. The garden is full. Dress ranges from super-elegant to T-shirt and jeans, but everyone is stylish. Le tout Venise is here to mark the opening of an exhibition commemorating the centenary of Peggys birth. Organised by one of her granddaughters, the exhibition has come here from New York, where it opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Solomon was Peggys uncle, though their two art collections were separate entities during most of her lifetime. The granddaughter, Karole Vail, is the only Guggenheim grandchild to work for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She is among the guests, in a Fortuny dress, elegantly echoing the Fortuny dress Peggy often wore. Her sister Julia and her cousins are there too six of the seven surviving grandchildren. Mark has not come. Fabrice died in 1990.

Philip Rylands is the curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. He has been in charge since the palazzo became a public gallery in 1980. Philip is English, and originally came to Venice from Cambridge University to research a doctoral thesis on Jacopo Palma (il Vecchio). He makes a speech in impeccable Italian. During it, as the light through the trees throws changing shadows on the people below, Mia, Julias daughter, the only one of Peggys great-grandchildren present, twenty-one months old, clambers onto Untitled (1969) by Robert Morris a huge rectangle of steel balanced on a massive section of steel dowelling, stretched horizontally on the ground. Mia runs up and down. Her activity turns a few heads.

After two hours, people have begun to filter away, and in another hour the garden will be empty. In a corner a stone slab set into a wall marks the resting places of Peggys beloved babies fourteen little dogs, until almost the end all pure-bred Lhasa Apsos, which in a series of generations shared Peggys life in the palace. Next to it is another plaque. On it is written: Here rests Peggy Guggenheim 18981979.

The party in 1998 filled the garden. Eighteen years earlier, on 4 April 1980, only four people were present for the interment of Peggys ashes. She had died an isolated death just before Christmas the previous year.

Although Peggys claim to fame is as one of the foremost collectors of modern art of the first half of the twentieth century, her offstage life as a restless combination of wanderer and libertine has attracted so much gossip, obloquy, scandal and delight that it has overshadowed her influence as a patron of painters and sculptors. When she was at the peak of her career, feminism was in its infancy and, apart from the Suffragette movement, not organised on any major scale. Men took it for granted that they had precedence over women, and it would be hard to find a more sexist bunch than the male artists who flourished between 1900 and 1960. Peggy took on their world with a mixture of low self-esteem and aggression, aided by money. She couldnt enter that world as an artist a difficult task for any woman at the time but she could use her money to buy a position in it. In her endeavours she never quite found herself, but she supported three of the most important art movements of the last hundred years: Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract-Expressionism.