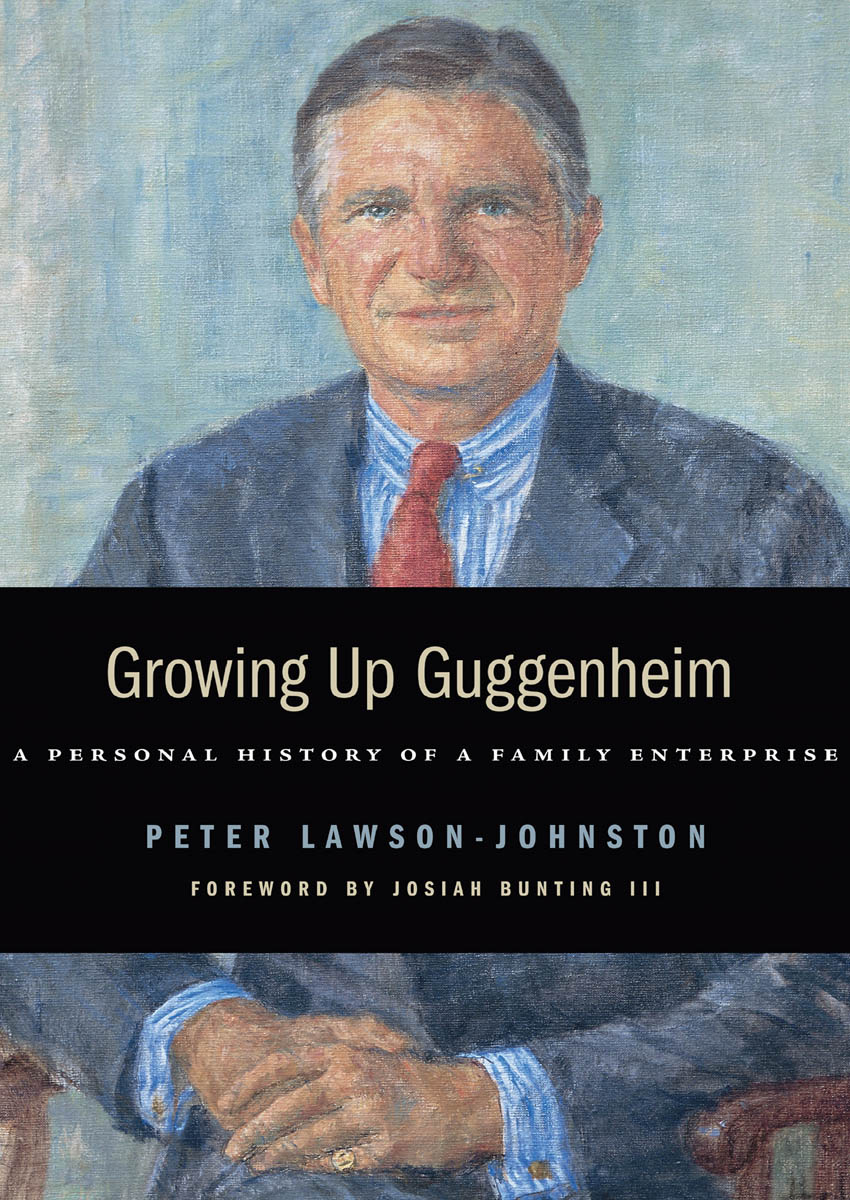

Growing Up Guggenheim

A Personal History of a Family Enterprise

P ETER L AWSON -J OHNSTON

foreword by

J OSIAH B UNTING III

WILMINGTON , DELAWARE

CONTENTS

Grandpa Solomon

The Museums Founding Father |

Growing Up Guggenheim

A Grandsons Unlikely Ascent |

Harry

The Heir Apparent |

Tom Messer

The Guggenheim Comes into Its Own |

Cousin Peggy

Return of the Prodigal Daughter |

Tom Krens

Toward a Global Guggenheim |

Epilogue

Global Art as a Family Enterprise

I

GRANDPA SOLOMON

The Museums Founding Father

My great-great-grandfather Simon and his son Meyer arrived in Philadelphia in 1848 from Lengnau, Switzerland, after a two-month sea journey. One of two towns in all of Switzerland where Jews were allowed to live, Lengnau had for generations offered Meyers ancestors neither opportunity nor security. Forbidden to own land, Lengnau Jews were allowed to work only as peddlers, tailors, or moneylenders. The Swiss authorities confiscated income beyond that which provided a meager subsistence.

In search of anything better than the bleak future preordained in their homeland, the Guggenheim family joined the great nineteenth-century European exodus to America. Virtually penniless, father and son became door-to-door peddlers. Meyer, in his early twenties, was particularly successful at selling stove polish to farmers and miners in the Pennsylvania Dutch country. Soon, the Guggenheims set up a business to manufacture stove polish and, later, something called coffee essence, a concentrate made principally of chicory.

By 1852, Meyer, at twenty-five, could afford to marry his nineteen-year-old sweetheart, Barbara Meyer, with whom he had fallen in love on the voyage to America. By 1873 they had eight sons and three daughters.

After Simon died in 1869 at the age of seventy-six, Great-Grandfather Meyer expanded the family business by becoming a wholesale spice merchant, manufacturer of lye, and importer of laces and embroideries. He and Barbara had eleven children: daughters Jenette, Rose, and Cora, and sons Isaac, Daniel, Murry, Solomon, Benjamin, twins Simon and Robert (Robert died at age nine), and William. A hard-driving man, Meyer was devoted to his family and determined to instill ambition in his seven surviving sons so that they could ultimately join him in the family business. Barbara, who had no interest in business, apparently was a truly dedicated mother who enjoyed that role enormously. In addition to creating a warm home for her family, Barbara instilled in her children a love of music and the arts and supported their philanthropic inclinations.

My great-grandfather Meyer Guggenheim

The children attended Catholic day schools in Philadelphia. In their late teens, Dan, Murry, and my grandfather Solomon were sent to Switzerland to learn the embroidery business. Upon their return, Meyer formed a partnership, M. Guggenheims Sons, giving each son an equal share, even though the older brothers shouldered most of the workload in the early years. A family story that passed down to my generation tells how Meyer once gathered all the brothers together, handed each a stick, and asked him to break it. He then had each brother attempt to break seven sticks together, which none could. His moral: in unity, strength.

In 1881, Meyer learned of a silver and lead mine in Leadville, Colorado, that was for sale because it was flooded. He invested in what became the famous A.Y. and Minnie Mines, which turned into a bonanza. Soon the Guggenheims were deep into the highly profitable mining business.

Grandfather Solomon, at thirty, was sent to Mexico in 1891 to supervise the construction of a smelter in Monterrey. Ive been told he carried a loaded revolver at all times and proved to his father and older brothers that he was both courageous and effective. Ultimately, the Guggenheims dominated copper, lead, and zinc mining and smelting in the U.S., owning or controlling American Smelting and Refining Corporation, Kennecott Copper, and others. In the years prior to World War I, the family had secured control over as much as 80 percent of the worlds copper, lead, and silver mines.

At the peak of their success they discovered the famous Chuquicamata Copper Mine in Chile, owned diamond-mining operations in the Congo and in Angola (in partnership with Thomas Fortune Ryan and Societe Generale de Belgique), gold mines in the Yukon, and copper mines in Alaska. When Meyer died at seventy-eight in 1904, he left each son a multimillionaire.

Their liquid assets were vastly increased in 1923, when my grandfather three of his brothers decided to sell Chuquicamata to the Anaconda Company for $70 million (more than $700 million in 2002 dollars). Because their decision was made over the objections of Dans son, Harry, and Murrys son, Edmond, the Chuquicamata sale scattered Meyers hallowed bundle of sticks for this and succeeding Guggenheim generations. Nevertheless, that 1923 sale left each of the Guggenheim brothers among the wealthiest men in the world, and each in his own way began to employ that wealth in ways so grand they soon eclipsed and obscured the roots of the family fortune.

Born in 1927, four years after Grandfather Solomon realized his share of those assetsand began spending them lavishlyI assumed, as children do, that his way of life was a timeless condition, not the magnificent exercise in semi-nouveau riche it actually was.

To say my grandparents lived expensively is a gross understatement, though to a measurable extent my grandfather had earned it, over and above his inheritance. My half-brother, Michael Wettach (who died in 1999), and I used to talk about the things we remembered most about our visits to Grandpa Solomon and Grandma Irene. In the end, the overwhelming luxury of their lifestyle left the most durable impression on us both.

As boys, we visited our grandparents most often at their palatial 200-acre estate, Trillora Court, at Port Washingtons Sands Point on Long Island. It encompassed a beautiful nine-hole golf course, which his deceased brother Isaac had built for himself upon learning that the Sands Point Golf Club wouldnt admit him (or any other Jew). I formed a lifelong attachment to golf on that course. A much-better-than-average golfer, Solomon was portrayed in John H. Daviss monumental 1978 book The Guggenheims as driving the ball past mossy baroque statues and fountains, formal Italian gardens, which as a youth I was too absorbed in the gameand still amto notice.

Trillora was designed in the Italian Renaissance style, an immense, square, forty-room structure surrounding an enclosed courtyard.The driveway was a curving, mile-long path of small, bluestone chips. I remember waking to the sound of the grounds crew raking that endless gravel ribbona Sisyphean task that began again each time a car passed over it. My grandfather and grandmother each had a chauffeur. When approaching the house, my grandmothers chauffeur, Gunther, would give the horn three short beeps, while my grandfathers chauffeur, Allen, gave one long blast. These codes alerted the footman exclusively assigned to my grandfather or grandmother to race from the back of the house to the front in time to open the gates and retrieve his particular charge.