Contents

Guide

The Business of Tomorrow

The Visionary Life of Harry Guggenheim

From Aviation and Rocketry to the

Creation of an Art Dynasty

Dirk Smillie

For Lorelei, beloved

Introduction

N itin Nohria, former dean of the Harvard Business School, once coauthored a study of how business leaders of the air age shaped the history of aviation. In his introduction, he admitted one bias: a passion for flying (and memberships in million mile clubs at three airlines). When Nohria left India for America, he arrived in a Boeing 747 jumbo jet. Some of my best memories are travels on airplanes.

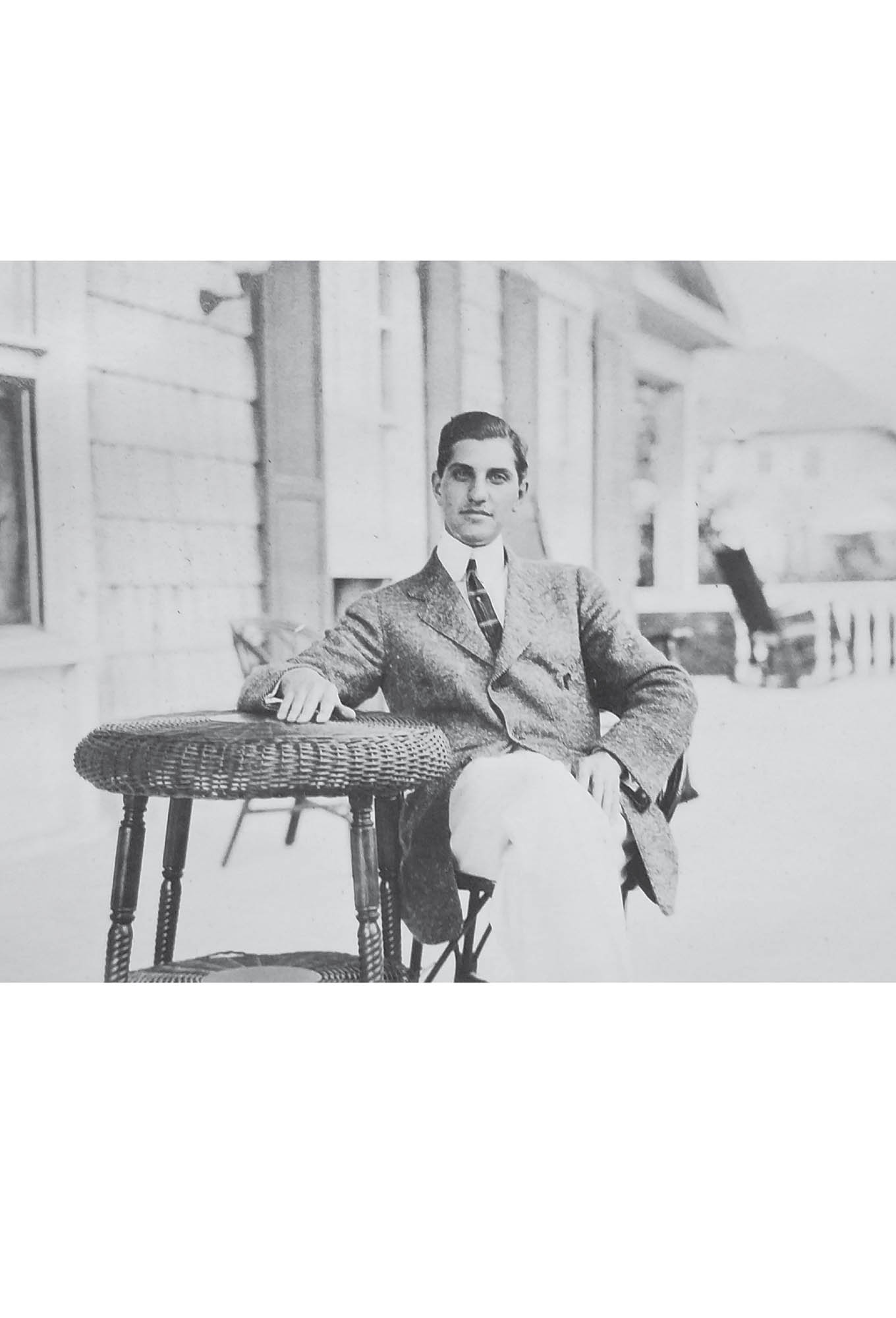

In the study, Nohria and his Harvard team revealed a hidden figure in aviationa foundational entrepreneurwhose influence they compared to digital pioneers Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Meg Whitman and Pierre Omidyar (eBay), and Larry Page and Sergei Brin (Google). The study concluded that this entrepreneur, having received scant mention in aviation history may have actually had more influence on the eventual growth of the U.S. airline industry than the Wright brothers. That entrepreneur was Harry Frank Guggenheim.

A pilot himself, who was obsessed with flying, Harry used every financial tactic he could think of to advance aviationmicrofinance, public-private partnerships, R&D grants, safety and design competitions, airplane reliability tours. At a time when most people had never seen an airplane, Harry believed aviation would one day be fundamental to the transportation infrastructure of the United States.

Using his familys great wealth, Harry bet big on flight technology and devised alternative metrics to assess the results. He helped create a viable business model for aviation and transformed public acceptance of flying. In doing so he jumpstarted the air age, possibly by decades. In fact, the very 747 Nohria boarded for America was invented by Joseph Sutter, graduate of an aviation engineering school funded by Harry Guggenheim.

At the turn of the century the Guggenheims operated the largest mining conglomerate on earth. Six decades later the Guggenheim museum opened, creating a landmark in New York and recasting the family as stewards of a global art brand. Harry carried the torch between the old and the new eras, connecting them with a record of aggressive philanthropy and entrepreneurship. Aviation was just the first chapter of Harrys life. Impact investor, technologist, start-up acceleratorHarry played a multitude of roles across five different sectors of American business, gambling large chunks of the family fortune on enterprises it had never been in.

For nearly a decade Harry was the sole financial backer of Robert Goddard, the father of modern rocketry. Goddards work became the foundation of the space age. From there, Harry went on to publishing and the arts. With wife Alicia Patterson, he cofounded Newsday, the nations most successful suburban newspaper. Late in life, he led the building of the Guggenheim museum, mediating between two contentious forces: architect Frank Lloyd Wright and the Guggenheims director, James Sweeney.

Those who knew Harry did not mince words in describing him:

- Fiorella LaGuardia, former mayor of New York City: the guy who put one over on me in Italy

- John Hanes, Roosevelts undersecretary of the treasury: He was a very brilliant man

- Frank Lloyd Wright, architect: Harry doesnt like controversy. Harry likes to win

- Charles Lindbergh: He was an extraordinary and wonderful man, and among my closest friends

- Thomas Messer, third director of the Guggenheim museum: a tyrant

- Madeleine Albright, former secretary of state the man who alternately charmed and intimidated us

- Bill Moyers, former LBJ press secretary and publisher, Newsday: His intuitions I found all admirable. It was his opinions that were not.

- Gen. James (Jimmy) Doolittle, WWII air ace: A great American

- Alicia Patterson, Harrys third wife and cofounder of Newsday: that son of a bitch

Harrys first two marriages, as he saw them, were his only true defeatstheir failures entirely his fault, he said.

As his investments weaved their way into the very fabric of American life, Harry made forays into politics and diplomacy. He had the ear of five U.S. presidents, spending time with each in the Oval Office. His years as U.S. ambassador to Cuba during the revolution were more than he bargained for, nearly costing him his life. Among his closest friends was Charles Lindbergha relationship that survived searing criticism on the eve of WWII.

Until now, Harrys story lay buried among the five major works produced on the Guggenheim family over the decades. Within those collective 2000 pages of family history, he remains a Delphic figure. A deeply private person, he left behind no journals, diaries, or memoirs. His letters to friends, family members, and business associates are at times revealing, but opaque when it came to his inner thoughts. He was patrician, at times aloof, and even those closest to him said he was a difficult man to figure out. Yet Harry clearly wanted to be understood and remembered. He bequeathed to the Library of Congress some 115,000 itemsa massive trove of consequential and quotidian memos, notes, correspondence, reports, legal papers, speeches, and business documents over six decades. He left his home, Falaise, to be administered as a museum, choosing how its furniture should be arranged and what items in his bedroom would be seen by visitors.

As a writer at Forbes for a decade, Ive been fascinated by stories of how great family business dynasties were built. Most do not last. Often the second or third generation doesnt possess the ambition or the imagination to carry on a family enterprise in a modern era. In many cases the next generation is simply content to enjoy their inherited wealth, making a career out of leisure. Harry chose a different path. The institutions he built over his lifetime, and the impact they continue to have, form one of the great business backstories of the 20th century.

CHAPTER ONE Bandits and Bullion

I

I n the summer of 1891, William and Solomon Guggenheim faced the most dangerous journey of their lives. Their destination was a small town in Mexico, where they would establish the next great outpost in the Guggenheim mining empire. They would bring the familys vast knowledge of extracting metals from the earth to a land whose enormous mineral wealth had been mined for centuries, yet remained largely untapped. In the coming years the Guggenheims would build railroads, hire steamboats, erect smelters, and construct entire mining towns to transform millions of tons of ore rich with copper, silver, lead, iron, zinc, and other metals that would find their way into newly electrified American homes, military munitions, automobiles, and factories. The metals unlocked from their mines in Mexico and elsewhere would fuel the Second Industrial Revolution.

But Mexicos earthbound riches lay untapped for a reason. For most of the 19th century Mexico was a land of unending war, political upheaval, and revolution. There was the War of Independence (ending Spanish colonialism); the Mexican-American War (losing Mexico one-third of its territory to the United States); the Caste War of Yucatn (touched off by the Mayan uprising of 1847); and the occupation of Mexico by France in the 1860s. Nearly every president of Mexico in the 19th century had been a military commander.