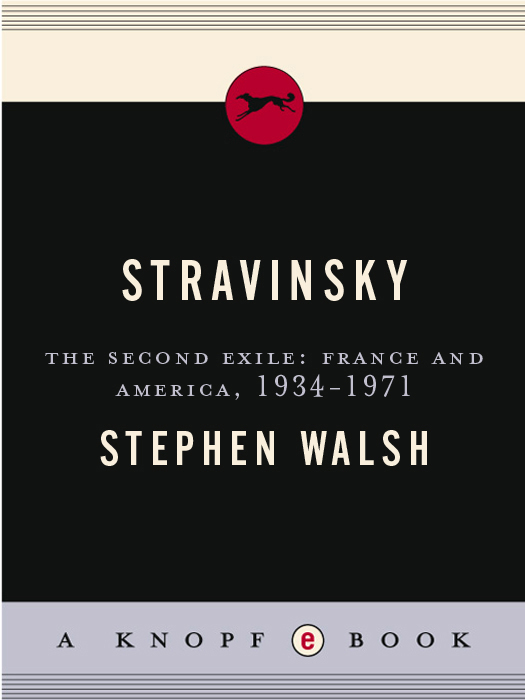

A LSO BY S TEPHEN W ALSH

Stravinsky: A Creative Spring

Russia and France, 18821934

The Lieder of Schumann

Bartk Chamber Music

The Music of Stravinsky

Stravinsky: Oedipus Rex

For Mary

Towards great persons use respective boldnesse.

GEORGE HERBERT

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M ANY OF THOSE whose names figure in the acknowledgments for the first volume have been at least as important to the second. In particular I should like to repeat my thanks to the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basle and its expert staff, to the library staff of Cardiff University, and to my colleagues in the Cardiff University Music Department, without whose supportpersonal as well as institutionalneither volume could ever have been written. The Paul Sacher Stiftung kindly gave me permission to quote from and reproduce a large number of documents and photographs in its possession. The Cardiff Music Department helped me with research money, and I was also supported by research grants from the AHRB and the Leverhulme Trust and by a years sabbatical under the AHRBs research leave scheme. Among the many other libraries and archives to which I am indebted, I should particularly mention the Harry Ransome Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the Department of Special Collections at UCLA, the Butler Library of Columbia University, the Stiftung Archiv der Akademie der Knste in Berlin, the London Library, the newspaper section of the British Library at Colindale, and the Music Division of the Library of Congress. In addition to those individuals mentioned in the introduction to volume 1, I should like to thank Petra Kupfer and Carlos Chanfn (Paul Sacher Stiftung) and Linda Ashton (HRC, Austin) for their particular and unstinting help.

I have made heavy demands on the time and patience of busy friends and colleagues. Anthony Powers, Arlene Sierra, Mark Almond, Shirley Hazzard, and Colin Slim all read the manuscript, pointed out errors or imprecisions, and suggested improvements. I am deeply grateful to them all. Others who have helped me, in a variety of often extremely substantial ways, are Gilbert Amy, the late Arthur Berger, Thomas Bsche, Pierre Boulez, Marilee Bradford, David Bray, Sally Cavender, Dorothy L. Crawford, Paolo Dal Molin, Teresa DArms, Valrie Dufour, Christopher Flood, Anthony Holden, Stephanie Jordan, Charles M. Joseph, Andrew Kemp, Lyudmila Kovnatskaya, William Kraft, Lourdes Lopez, Alan Maclean, John McClure, Russell McCulloh, Nolle Mann, Belinda Matthews, David Matthews, Edward Mendelson, Carol Merrill-Mirsky, Roger Nichols, Susan Palmer, David Raksin, Nancy Reynolds, Sir Adam Ridley, Julia Rosenthal, Ann Schreffler, Stanislav Shvabrin, Nigel Simeone, the late Leonard Stein, Jonathan Stone, Irina Vershinina, Claudia Vincis, and Jerry and Helen Young. I repeat that these are merely my more recent benefactors, in addition to those already named in volume one.

The second volume has had one major category of help not available to the first. Stravinskys own close family, who had initially preferred to distance themselves from the project, changed their minds (as I believe) when they saw that it was not simply a new painting of old pictures. In particular I should like to thank the composers daughter, Milne Marion, and place on record the kindness of his late daughters-in-law, Denise Strawinsky and Franoise Stravinsky, in welcoming me to their homes and talking to me at great length about him. The composers grandson, John Stravinsky, was no less hospitable, and also gave me a huge amount of material assistance, kept me informed about the emergence of new letters and documents, allowed me to read everything in his possession, and, as in the first volume, allowed me to quote from private letters and copyright materials. Without his support, the first volume could not have been published in its intended form, but the second volume could scarcely even have been written. I am hugely indebted to him and his wife, Dava.

Writings by Isaiah Berlin are reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown on behalf of The Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust (c) 2004 by The Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust.

Extracts from Goodbye to Berlin, Lost Years, and Diaries by Christopher Isherwood, published by Chatto & Windus, are reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd.

Letters of Chester Kallman are quoted by permission of the literary estate of Chester Kallman.

Writings by Lincoln Kirstein are (c) 2006 by the New York Public Library (Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations) and are quoted by permission.

Quotations from And Music at the Close by Lillian Libman are copyright (c) 1972 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., and are used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Writings by Francis Steegmuller are quoted with the kind permission of Shirley Hazzard Steegmuller.

Extracts from the writings of Dylan Thomas are reprinted by permission of David Higham Associates and Harold Ober Associates.

For permission to quote from other copyright materials, I should like to thank the following: Pierre Boulez, Martin Duberman, the Fondation Internationale Nadia et Lili Boulanger, Leopold Godowsky, Doris Halsey (for the Huxley Literary Estate), Marie Iellatchitch-Strawinsky, Nicholas Jenkins, Milne Marion, Edward Mendelson, Madeleine Milhaud, Daniel Milhaud, Dominique Nabokov, Marie-Victoire Nantet, Oliver Neighbour, Fabio Rieti, Marion Sapiro, Myriam Scherchen, and Jeff Towns.

I reiterate with sorrow my abiding debt to my Moscow colleague, Viktor Varunts, who continued to supply me with Russian-language material from the composers and other archives until his tragic death from a heart attack soon after his arrival in New York at the start of a Fulbright scholarship in September 2003. Varuntss three published volumes of Stravinskys Russian-language correspondence are a wonderful memorial to a great scholar, a memorial edged only with the sadness that the two additional volumes that he was preparing surviveand seem likely to remainonly in draft form. I was nevertheless able to make use of the correspondence intended for these volumes, which Varunts had supplied to me before his death, alas without the commentaries and appendixes which adorn the published volumes.

My debt to my wife and family hardly needs stating but is partly and inadequately expressed in the dedications of the two volumes. Living with somebody elses obsession is probably even worse than living with ones own. I cant thank them enough, and will not try.

When the first volume, Stravinsky: A Creative Spring, came out in 19992000, my mother was already too poor-sighted to read it. One day, a fairy godfather arrived in the person of Nigel Davis, a High Court judge who, in his not very considerable spare time, did voluntary work visiting the elderly and housebound. He struck up what seemed at the time a somewhat unlikely friendship with my mother, and since then has spent several hours on most Saturday afternoons reading her sons book to her and (Im slightly afraid) discussing its contents. I am moved by his kindness every time I think about it, and can only hope that he will not blench at the realization of what still remains. A creative spring: all right. But a second exile? Thats a lot more Saturday afternoons.

STEPHEN WALSH

Welsh Newton, September 2005