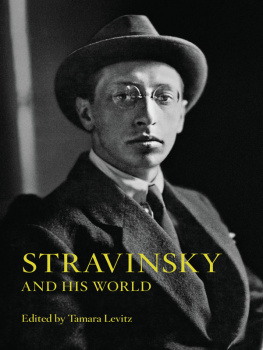

Stravinsky and Balanchine

Stravinsky & Balanchine

A JOURNEY OF INVENTION

Charles M. Joseph

Copyright 2002 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Set in Adobe Garamond and Stone Sans types by

The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America by Edwards Brothers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Joseph, Charles M.

Stravinsky and Balanchine : a journey of invention / Charles M. Joseph.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-300-08712-8 (alk. paper)

1. Stravinsky, Igor, 18821971. Ballets. 2. Balanchine, George.

3. Ballet. 4. Choreography. I. Title.

ML410.S932 J665 2002

781.556092dc21

2001007130

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jennifer and Amy

Contents

Preface

My youthful introduction to the music of Igor Stravinsky came by way of The Firebird. The musics memorable melodies and colorful orchestration shimmered. Curiosity quickly led me to Petrushka, with its seemingly aberrant rhythms and even more bizarre harmonies. Finally, a friend (with a knowing smirk on his face) suggested that I listen to The Rite of Spring. Initially it seemed a blur, an unbridled, alluring jumble of dissonance gone over the edge; consequently, it immediately fascinated me. Each score drew me in more deeply, although my reaction was entirely visceral. Although I couldnt yet articulate what I was experiencing musically, let alone intellectually, I knew that I was hopelessly hooked. As for all three pieces being ballets... I hardly gave that a moments thought. Id never seen any of them staged and knew next to nothing about dance. Besides, Stravinskys music seemed to speak forcefully enough on its own merits, so why muddy the waters with some supplementaland surely extraneousvisual embellishment?

Eventually, of course, I did see all three landmark ballets danced. Although I wasnt quite sure what to expect, I remember that as thrilling as these productions were, they left me a little disconcerted. The combined choreography and music struck me as a mismatch, to use T. S. Eliots description of The Rites 1921 revival. As a musician, I didnt sense a musical-choreographic parity, let alone the artistic synthesis I had expected. I realize now that my view was both narrow and uninformed. For one thing, it was historically decontextualized. In the world of 191013, when all three ballets premiered, it was neither necessary nor even particularly desirable to think primarily in terms of synthesis; nor was the concept of a genuine, coherent artistic synthesis universally defined. Most relevant, dance and music were not always considered equal partners. Later, in the hands of Stravinsky and George Balanchine, they became so.

As a ballet composer who understood the language of dance better than any other musician of the twentieth century, Stravinsky needed to find an artista very sympathetic artistcapable of complementing his own clearly envisaged ideas. Visualizing music in terms of correlative physical movement that would, above all else, serve the composers score was the crucial issue. And although this was hardly the only way to conceive choreography, for Stravinsky it was an unconditional, nonnegotiable assumption. Balanchine, given his own background and beliefs, perhaps more than any choreographer before or since had no qualms in accepting this sine qua non. This mutual understanding formed the crux of their partnership.

Some have argued that Balanchines submissive acceptance amounted to acquiescence. But in fact, the Stravinsky-Balanchine partnership was much more elastic, much more contrapuntal than might first appear. As a choreographer, Balanchine was primarily in the business of relating the movement of human bodies to one another. He was interested in the inherently fundamental tensions of theater and drama. He wanted to explore all types of counterpoints: male and female, spatial, rhythmic, and most broadly, aural-visual symmetries. Similarly, Stravinsky looked upon the art of composition as nothing more than relating one note to the next, although typically, his tersely phrased pronouncement, calculated to come across as provocative, belies a deeper complexity. How the sequence of those notes would be orderedharmonically, linearly, texturally, structurally, rhythmicallythis is what constituted the compositional interplay of musical elements. It was all a matter of selecting the one right relation, the right order, and most important, the right balance. Balance was everything.

Simply put, no one balanced Stravinsky better than Balanchine. From the start, he was the ideal partnerthe perfect collaborator, as Stravinsky referred to him. The ballets they forged together stand as one of the most extraordinary collaborative triumphs of the twentieth century.

But why Balanchine and Stravinsky? What was it about the choreographer that enabled him to illuminate the composers music so vibrantly and, by Stravinskys own admission, so instructively? Just as I can recall first hearing The Firebird, so I can remember my first viewing of Apollo, which left an even more indelible impression. And just as I could not at first verbalize why the music of Petrushka had so mesmerized me, neither could I initially explain why Balanchines choreography for an already dynamic score like Agon widened my understanding all the more.

Intuitively I understood that Balanchines sense of movement counterbalanced the music in a way that was neither superficially nor superfluously imitative. His control of motion visually concretized musical relations otherwise likely to have been missed. His choreography didnt offer banal derivatives or garnish the music by adding another layer, nor did he allow the music to function as a subsidiary platform for the dance. In my viewing of Apollo and all the subsequent Stravinsky-Balanchine ballets, it seemed to me that the musically astute choreographer possessed the uncanny gift of clarifying what my ears heard through what my eyes saw. Musicians may argue that I am giving Balanchine too much credit. They might contend (even as Stravinsky himself sometimes did) that the composers music did just fine on its own. Even Balanchine quipped that if you didnt like the dancing, you could close your eyes and listen to the music, since it was more important anyway. On the other hand, dancers may feel Ive unfairly minimized the choreographys importance. After all, whos onstage and whos in the pit? For myself, I must confess that as compelling as the music is, I now actually need the choreography for Apollo and Agon. Physical movement and sound complete each other in a fulfilling equilibrium, an artistic sum that in this case is more expressive than its two separate parts.

Violette Verdy, one of Balanchines most musical ballerinas, remembers that the choreographer thought of dance as musics younger sister. By his own insistence, when it came to Stravinskys music Balanchines only goal was to illumine the score, not to decorateand certainly not to subsumeit. How he managed to attain that goal is what magnetized me when I first saw

Next page