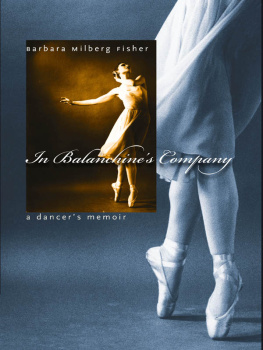

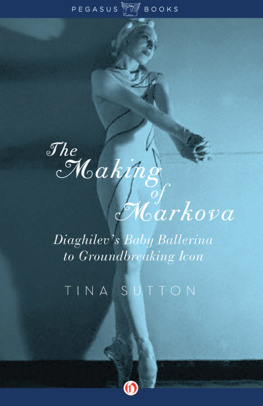

In Balanchines Company

BARBARA MILBERG FISHER

In Balanchines Company

A Dancers Memoir

Wesleyan University Press

MIDDLETOWN, CONNECTICUT

Published by Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

Copyright 2006 by Barbara Milberg Fisher

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to reproduce the following:

Verse lines from Among School Children, by William Butler Yeats, reprinted with permission of A. P. Watt Ltd on behalf of Michael B. Yeats.

Lines from The Idea of Order at Key West and The Planet on the Table, by Wallace Stevens, reprinted by kind permission of the Knopf Publishing Group, and courtesy of Peter Reed Hanchak, Executor, Estate of Wallace Stevens.

Allegro Brilliante, Symphony Concertante, Firebird, Orpheus, Divertimento No. 15, The Four Temperaments, The Nutcracker, Ivesiana, Agon, The George Balanchine Trust. BALANCHINE is a trademark of the George Balanchine Trust.

first appeared in Global City Review.

All efforts were made to locate the copyright holders for the images used in this book.

Frontispiece: George Balanchine (mid-1950s). Photographer unknown, authors collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fisher, Barbara M. (Barbara Milberg), 1931

In Balanchines company : a dancers memoir / Barbara Milberg Fisher.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 9780819568076 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0819568074 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Balanchine, George. 2. DancersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

GV1785.A1F57 2006

792.82092dc22 2006004524

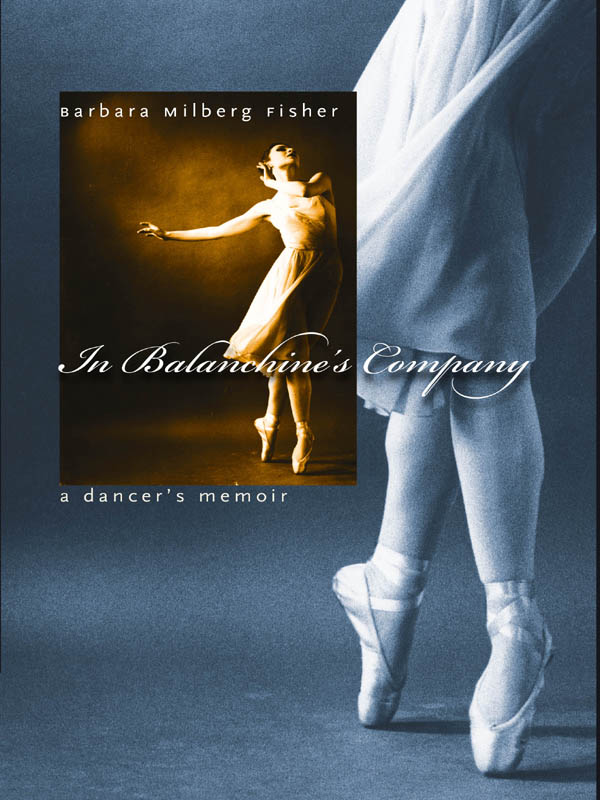

Cover illustration: Barbara Milberg in Allegro Brilliante (1956). Photograph by Zachary Freyman, from the authors collection.

For Alice and Leonard

True genius doesnt fulfill expectations, it shatters them.

Arlene Croce

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

William Butler Yeats

Foreword

ARLENE CROCE

I celebrate the life of the dancer. She starts her training early. At eleven or twelve, she possesses the kind of body, ease of coordination, and elegance of bearing that immediately make her the envy of all who look upon her, and their mothers. She does not go through an awkward age. She does not get fat. She quickly becomes independent: she can be a fully fledged professional, with a paycheck, before she is out of her teens. If she is good enough to join one of the top companies, she gets to travel the world free and go to foreign-embassy parties, where she is received with honor as a representative of her country. (This was especially true during the Cold War, the time-frame of this book.) Finally, when she retires, she is still young enough to get married or start a new career.

This perfect life, as I see it, is exemplified in the life of Barbara Milberg Fisher. I should wish to have led itprovided, of course, I could still have had my own life in the end. And provided Id had the talent in the beginning. To have spent ones youth dancing in the greatest of American companies, even if that were all that Barbara Milberg Fisher ever did, would be a major achievement. How it happened, the who-when-where, is not something she dwells upon here; it is for us to infer the unique combination of the historical and the personalthe gift of fortune that led her to Ballet Society just as it was being formed, and the gift of a dance talent musical by nature, bolstered by years of training as a classical pianist (oh, to be a pianist!). And that is how Barbara became a dancer of value to George Balanchine.

She danced for Balanchine during one of the most productive periods of his life and, after polio struck his wife Tanaquil Le Clercq, one of the most catastrophic. It is my loss not to have known the company well at that time. I could barely tell one dancer from another. When I saw Barbara in the original cast of Agon, it was without realizing precisely who she waswithout realizing anything, really, except that, in this latest of Balanchines creations with Stravinsky, I was witnessing something historic. It is amazing how fast the current was moving in the late fifties. Before I had a chance to form an adequate impression of Milbergs dancing, she had left the company, and what did she do but join Jerome Robbinss newly assembled Ballets: USA, surely one of his peak creations.

But all this is me peering in from outside. What the life and times of a dancer were actually like, only she can tell. She has her dinner-table stories (and there are some hot ones), and no doubt she has her regrets, but the equanimity with which she writes of herself as a typical young dancer of the fifties tells us that they are of little consequence in a much longer life of accomplishment. Barbara Milberg gave up dancing at the age of thirty-one, had children, and launched another career fully as demanding as dance but in no way touching it. When we met, she had been for a number of years a distinguished member of the faculty of the City College of New York, a teacher of English literature, and a scholar who had written to acclaim on Milton, Henry James, Borges, and Wallace Stevens. In this memoir, she concentrates on Balanchine, who has quite obviously continued to provoke her thought. She takes us back to a precious golden age in New York cultural history, the era of the extended by popular demand seasons at the City Center and the triumphant tours abroad. No one, I think, has evoked so well the camaraderie of company life in the years when American ballet was struggling for world recognition. Morale was at an all-time high, and it showed. Think of Symphony in C at curtain rise: the lovely bodies motionless but energized, ready to begin. As Milberg puts it here, Never again would I feel such a charged, all-engulfing sense of purpose.

Although she long ago gave up the dancing life for the life of the mind, although her personal life has been a rich one, and her academic achievements are a matter of record, one feels that, for Barbara Milberg Fisher, nothing supersedes the memory of once having been part of a magic circle. That memory is the treasure she imparts to us now.

Acknowledgments

A memoir, it turns out, is all about other people. And a book of recollections with George Balanchine as its central focus will touch on a lot of other peoplemanagement, stage crew, wardrobe personnel, conductors, composers, musicians, designers, costumers, teachers, other choreographers, old cronies, and generations of dancers. Such a project consults extant memoirs and biographies; it reflects the work of scholars and librarians, has recourse to critical writings and reviews, profits from the laborious assembling of archives and special collections. For me, the richest outside source has been the extraordinarily vivid memory of dancers I worked with so many years ago. I should like to thank them, along with colleagues, friends, and various specialists who, over a period of years, helped to infuse this endeavor with some measure of heart, muscle, and accuracy.

Vida Brown Olinick, dancer, Ballet Mistress, friend, contributed generously and perceptively, with an exquisite eye for detail. Among other dancers whose memories might shame an elephant are Melissa Hayden, Ann Inglis, Una Kai, Robert Barnett, and Roy Tobiasthe last two graced with simply phenomenal recall. Early on, both Barbara Walczak and Edward Bigelow kindly took the time to clarify ambiguities and share information, while Allegra Kent lightened my labor with humor and authorial understanding.

Next page