STRAVINSKY AND HIS WORLD

For Brian Cherney

for introducing me to the music of Igor Stravinsky

STRAVINSKY

AND HIS WORLD

EDITED BY TAMARA LEVITZ

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

For permission information, see pages xvxvi

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013937053

ISBN: 978-0-691-15987-4 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-0-691-15988-1 (paperback)

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This publication has been produced by the Bard College Publications Office:

Ginger Shore, Project Director

Karen Walker Spencer, Designer

Anita van de Ven, Cover Design

Text edited by Paul De Angelis and Erin Clermont

Music typeset by Don Giller

This publication has been underwritten in part by grants from Furthermore, a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund and Helen and Roger Alcaly.

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

JONATHAN CROSS

|

INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY TAMARA LEVITZ

TRANSLATIONS BY BRIDGET BEHRMANN, KATYA ERMOLAEV, LAUREL E. FAY, ALEXANDRA GRABARCHUK, AND TAMARA LEVITZ

|

TATIANA BARANOVA MONIGHETTI

|

GRETCHEN HORLACHER

|

KLRA MRICZ

|

INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY KLRA MRICZ

TRANSLATION BY BRIDGET BEHRMANN, KATYA ERMOLAEV, YASHA KLOTS, TAMARA LEVITZ, KLRA MRICZ, AND BORIS WOLFSON

|

TAMARA LEVITZ

|

INTRODUCTION BY LEONORA SAAVEDRA

INTERVIEWS TRANSLATED BY MARIEL FIORI

IN COLLABORATION WITH TAMARA LEVITZ

DOCUMENT NOTES BY TAMARA LEVITZ

|

VALRIE DUFOUR

TRANSLATED BY BRIDGET BEHRMANN AND TAMARA LEVITZ

|

SVETLANA SAVENKO

TRANSLATED BY PHILIPP PENKA

|

LETTERS TRANSLATED BY PHILIPP PENKA WITH ALEXANDRA GRABARCHUK

INTRODUCTION, COMMENTARY, AND NOTES BY TAMARA LEVITZ

|

LEON BOTSTEIN

|

Preface and Acknowledgments

Stravinsky liked to boast to journalists about his worldwide success as a composer. During a chatty interview with Rafael Moragas in Barcelona in 1925, included in this volume, he described in a bemused fashion how two thousand old ladies had honored him at an event in Philadelphia by attempting to kiss his hand. He had put a halt to the proceedings by announcing through a megaphone that he needed his precious limb to conduct future concerts, and that they would have to stop. In spite of the playful annoyance he expressed in telling the story, he clearly relished the adulation.

Fame shaped Stravinskys career. His ascent to international stardom began for all intents and purposes in May 1913, when Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the Ballets Russes, orchestrated a riot at the premiere of The Rite of Springa marketing ploy that made Stravinsky an overnight sensation and that proved so successful that it continues to be used to draw audiences to performances of the work today. From the moment that Diaghilev conflated aesthetic appreciation and capitalist desire by transforming the premiere of The Rite of Spring into scandal, Stravinskys music stood in the shadow of his celebrityhis compositional innovations paling in comparison to the symbolic, commercial power of his brand.

Stravinskys celebrity was no exception in the history of modernism. On the contrary, as Jonathan Goldman argues, celebrity and modernism were mutually constitutive, both serving the goal of reaffirming the centrality of the individual in mass society in the early twentieth century. In Modernism Is the Literature of Celebrity, Goldman explains how Oscar Wilde inaugurated modernist celebrity culture in the 1880s, by turning his extraordinary self-production as a psychological subject into an object or stereotype to be admired by the massesand this shortly after the worlds first legal trademarked image, the red triangle on Bass Ale, was registered in England. Modernist writers followed suit, mobilizing the technologies of consumer culture to promote their writings and themselves in the decades that followed. James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and others fetishized authorship, transforming their signatures into brands, and making style a basis for objectifying themselves as inimitable individuals. The knowledge of their complicity with celebrity culture allows Goldman and others to explode myths about the great divide between modernism and popular culture, and about the modernist artist as isolated, disinterested Romantic genius.

Stravinsky adopted Wildes culture of the dandy, stylizing himself as an object of desire for the concert-going public while, behind the scenes, flaunting his conspicuous consumption and aristocratic buying habits. After 1913, he was almost always on display: posing for photographs (a medium crucial to the development of modern celebrity), marketing his work in an astonishing number of almost daily interviews in multiple languages (leading Richard Taruskin to conclude in an article in the New York Times in 2008 that Stravinsky lived in a perpetual state of interview), and calculating how to reproduce and disseminate his works using the most advanced technological means. Friendsamong them Arthur Louri, Pyotr Suvchinsky, Walter Nouvel, Alexis Kall, and Robert Craftserved as Stravinskys unofficial public relations agents, mediating his contact with the outside world and ghostwriting press releases and publications. Craft dedicated his career to consolidating Stravinskys celebrity during his lifetime, and to perpetuating it in publications and recordings after his death.

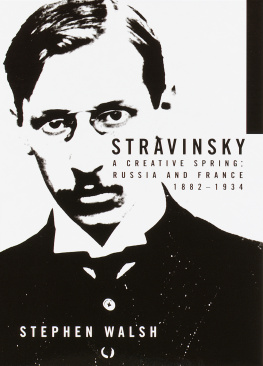

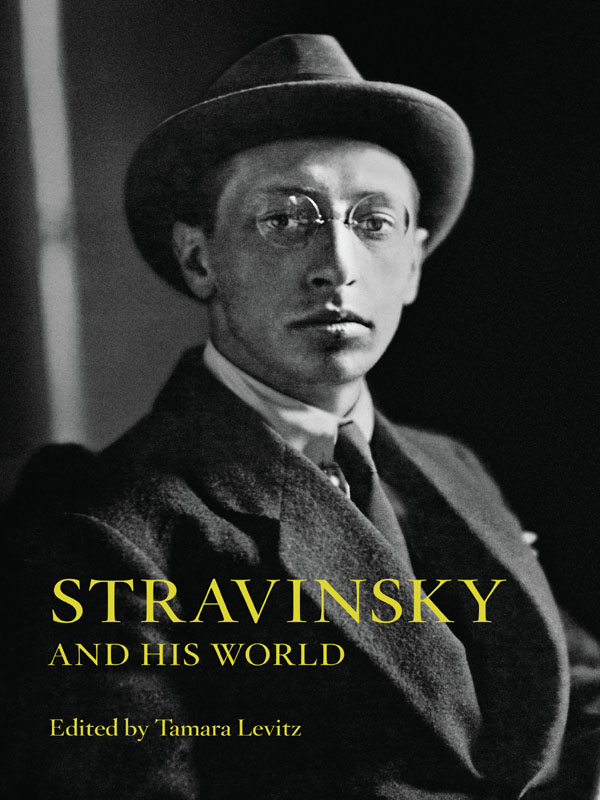

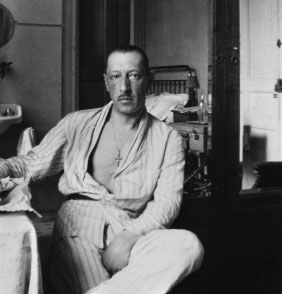

Figure 1. Stravinsky in Haarlem, the Netherlands, 1930.

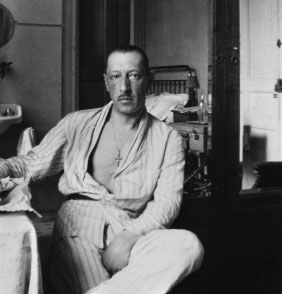

Stravinsky designed his words, images, and sounds to sell his celebrity by manufacturing musical need. In his own words, quoted in this volume, music should be desire, not habit. A photograph from 1930 (see ). Veras photographs appear to offer access to Stravinskys intimate universethe man behind the mask as Stravinsky scholars like to say. But the fact that she and Craft published so many of them in luxury editions after Stravinskys deathfor example, in Igor and Vera Stravinsky: A Photograph Album, 19211971suggests that, far from revealing an authentic reality about the composer, they too are designed to sell his image. Such private photographs highlight Stravinskys charisma, dogma, class, earthiness, passion, licentiousness, and virilityqualities the press had associated with Stravinsky and his music since The Rite of Spring. These photographs perpetuate the very traits that have enabled Stravinsky to maintain his celebrity for over a century.

Figure 2. Stravinsky in Nice, 1924.

Yet Stravinskys fame has sat uncomfortably with music scholars. Biographers and critics struggle to abandon deeply-held beliefs about modernist composers as exceptional individuals who express sincerely inner psychological states through word and music, and whose authentic dedication to their art allow them to escape the demands of the market. Such beliefs have led some of Stravinskys biographers to mistrust the trappings of his famewhether his commercial successes or the publicity machine that has generated themand others to adopt a Cold War hermeneutics of suspicion that has led to conspiratorial theories about the composers innate yet denied Russianness, or about his secret rightwing political agendas.

Next page