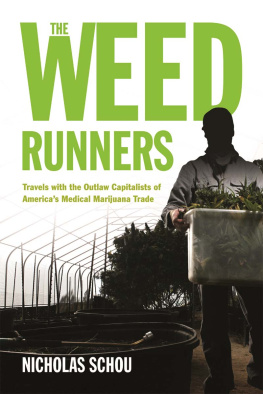

Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade

Peter Maguire and Mike Ritter

Foreword by David Farber

Columbia University Press

New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53556-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Maguire, Peter (Peter H.)

Thai stick : surfers, scammers, and the untold story of the marijuana trade /

Peter Maguire and Mike Ritter.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16134-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53556-4 (electronic)

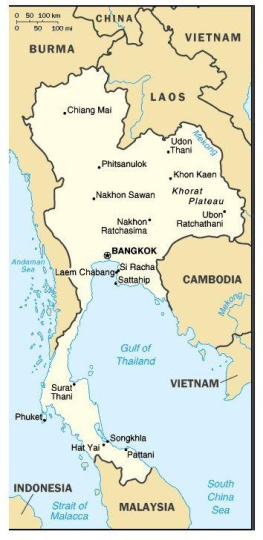

1. Marijuana industryThailand. 2. Drug trafficThailandHistory. 3. SmugglersThailandBiography. I. Ritter, Mike. II. Title.

HD9019.M382T553 2014

363.4509593dc23

2013008590

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design by Phil Pascuzzo

Cover image by iStockphoto

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

When Innocence Must Become Experience

In the broken-down realm of the American domestic empire of the 1960s and 1970s, a self-selected crew tried their hand at living free and unencumbered by the dictates of social convention and legal authority. From a polite distance, the label counterculture was attached to the most obviously disaffiliated of this particular mixed bag of heroic cultural rebels, drug-addled dropouts, predatory longhairs, idealistic communards, and clueless day trippers. The label was useful in promoting full-color magazine spreads of hippies and flower power marketing campaigns but said little about the lived experience of people who had decided to organize their lives outside of the day-in-and-day-out of institutional life in America. That new life, often enough, began as an innocent lark. It rarely ended that way.

The young people who went on this trip to a place with no name had their reasons, and those reasons were not all the same. Those with artistic visions and, in some cases, talent found pattern and inspiration in the long lineage of bohemian avatars that spoke across the generations, preaching of a rucksack revolution and Eastern mysteries. Others found their source in outlaw territory1 percent motorcycle clubs and old-school gangsters. And in an age when black, brown, and yellow colonized people were overthrowing centuries-old yokes of oppression, a percentage of white youths saw a world in which every old hierarchy of control was up for grabs. The evil lie of Vietnam played its part too, as did every other vestige of state-sponsored Cold War horror, especially the grotesque threat of atomic Armageddon. But all were not driven by despair or high-minded pursuit of Truth. Even as troubles came down the road, the sixties was a triumphal time of consumer plenty and unprecedented prosperity, and some young folks simply wanted to extend their egos and their pleasures as far as their gifts and their courage would take them. There were pushes and there were pulls, and nobody said you had to pick just one path or lineage of rebellionplenty of people mixed and matched, and that haphazard mlange made the era what it was.

For those who chose to live out their disregard for the status quo in the 1960s and early 1970swhatever their formula for rebellionthe near-sacramental use of cannabis, LSD, and other hallucinogens gave a commonality of expression and practice to the collective mission. For many, it was the drugs that opened up their personal rabbit hole. Without those particular drugs, the cultural rebellion would have looked and felt and been different. Illegal drugs gave the counterculture its style, its attitude, and its dead certainty that living outside the law was a material necessity. Those drugs and the peculiarities of the times combined to create an anthropologically specific liminal realm, an illegal nation that crossed borders, in which the rules had to be made as the game was played.

Much has been made, then and now, of the most visible of the countercultures pied pipers. Timothy Leary, who was simultaneously charlatan and shaman, appeared on TV and in gentlemens magazines pitching LSD. Allen Ginsberg, in his robes and beard, was everywhere, spreading mystical good cheer. The Diggers organized the Haight-Ashbury; the Yippies made their political play; and famous rock bands from the Grateful Dead to the Jimi Hendrix Experience to the Beatles disseminated their druggy truths and half-baked claims to millions of young people who wanted something more than what their parents and teachers and bosses offered them. Whatever role these marketers of cultural rebellion playedand it was not inconsequentialthey offered only a road map, not the trip itself. The high-octane fuel had to come from somewhere else.

The countercultures means of production was, above all else, mind drugs, especially LSD and cannabis. Producing those drugs for the multiplying number of young people who wanted in on the experience was, for a relatively small bunch of intrepid risk takers, an opportunity to make a living out of a way of life. Like the counterculture itself, these drug operatives were shape shifters; they could not and did not stay stuck in time. They made the counterculture possible and they got made by it. But the life they chose, supplying the drugs that made tens of millions see the world in a different light, put them outside the law. And outside the law, hard men and hard choices abounded. Nobody stayed innocent, and many of the men who signed up as drug smugglers and dealers, especially at the tail end of the love generation, never expected or wanted anything else but a life of hard kicks and out-of-the-box adventure. For most, hippie ethos aside, money played a not-insignificant roleeither as source for life-expanding good times or as tool for an extended voyage into the best an outlaw life had to offer.

Nearly a half century after this business was begun, we are still patching together the history of an epic undertaking. Given the scale, scope, and creative genius of the illegal drug industry in the 1960s and mid-1970s, how little is known about it is astounding. Its like only vaguely knowing how the steam engine changed the world in the nineteenth century. The countercultural inventors and their international compatriots of this critical form of deviant globalization changed the trajectory of modern economic development, even as they opened up the minds eye of a generation of young people in the United States, Western Europe, and other points around the world.

The story you are about to read shouldand there are no other words for itblow your mind. The menand the relatively few womenyou are going to meet took chances on land and sea to make a market in highly potent marijuana. They went from smuggling small loads of weed across the Mexican border to introducing massive shipments of Thai sticks to an international market looking to get stoned in ever more precise and potent ways. These smugglersscammers, as they called themselveswere a mixed bag: a wild bunch of surfer Robin Hoods, crooked watermen looking for their main chance, happy-go-lucky pirates, sweet-talking, back-stabbing narcissists, and deadly sociopaths.