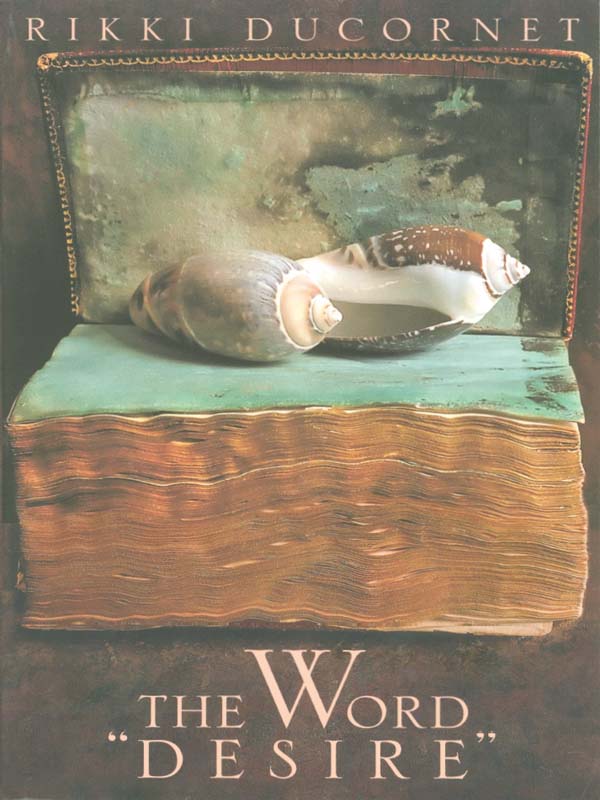

Rikki Ducornet is linguistically explosive.... Shes one of the most interesting American writers around.

Nation

An exquisitely crafted work of art, ribbed by paradox and opening to revelation, at once profoundly sensuous yet succulently moral. A treasure.

Robert Coover

Astonishing, a complex fantasia redolent of Swift and Borges, but stranger than both.

Times (London)

Dark, elegant, and exotic. Ducornets stories are meticulously crafted, striking unexpected notes that are as breathtaking as they are troubling.

Katherine Mosby, author of Private Altars

Ducornet has all her literary weapons workingher earthy and wildly funny imagination and her soaring prose and storytelling gifts.

Washington Post

OTHER BOOKS BY RIKKI DUCORNET

The Complete Butchers Tales

The Cult of Seizure

Entering Fire

The Fan-Makers Inquisition

The Fountains of Neptune

Gazelle

The Jade Cabinet

The Monstrous and the Marvelous

Phosphor in Dreamland

The Stain

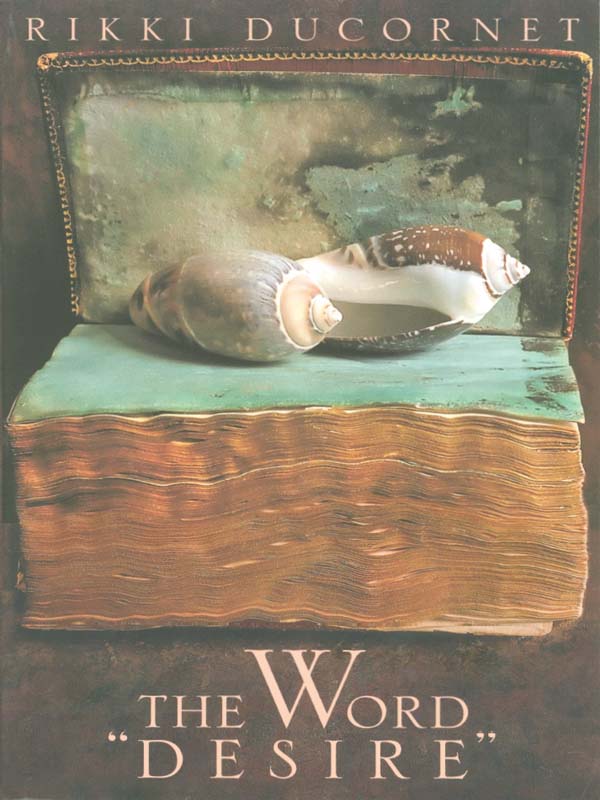

First published by Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1997

Copyright 1997 by Rikki Ducornet

First paperback edition, 2005

All rights reserved

Stories in this collection have appeared in Conjunctions, Parnassus, and The Iowa Review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Ducornet, Rikki, 1943

The word desire / by Rikki Ducornet. 1st Dalkey Archive ed.

p. cm.

Contents: The chess set of ivory Wormwood Roseveine Das Wunderbuch Vertige dor The many tenses of wanting The student from Algiers The foxed mirror The neurosis of containment Fortun Opium The word desire.

ISBN: 1-56478-398-7 (acid-free paper)

ISBN: 978-1-564-78991-4 (e-book)

1. Erotic Stories, American. I. Title.

PS3554.U279W67 2005

813.54dc22

2004063484

Partially funded by grants from the Lannan Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency.

Dalkey Archive Press is a nonprofit organization located at Milner Library (Illinois State University) and distributed in the UK by Turnaround Publisher Services Ltd. (London).

www.centerforbookculture.org

Printed on permanent/durable acid-free paper and bound in the United States of America.

FOR DOROTHY WALLACE

Each thing is merely the limit of the flame to which it owes its existence.

MAX SCHELER,

Nature et forme de la sympathie

The author wishes to express her thanks to Sandra Dijkstra, Tracy Brown, Greg Robbins, and Catherine Kasper for showing up at precisely the right moment.

Chess appealed to my fathers delight in quietude, his repressed rage, his trust in institutions, models, and measured behavior. Chess justified what Father liked best: thinking about thinking. He called it: battling mind.

Father dwelled in a space of such disembodied quietness his Egyptian students called him His Airship, I believe with affection. Chess allowed Father to make decisions that would in no way influence the greater worldbeyond his grasp anywayand to engage in conflict without doing violence to others or to himself. (Fathers fear of thuggery suggested clairvoyance when in a later decade he would find himself undone by a handful of classroom Maoists who called him Gasbag to his face. If clearly they intended to hurt him, they were, admittedly, responding to that disembodied quality of his already evident in Egypt, and his pedantrya quality rooted in timidity.)

Father was a closet warrior, a mild man and an intellectual, a dreamer of reason in a world he feared was chronically, terminally unreasonable. And he was a parsimonious conversationalist. His favorite quote was from Wittgenstein: What we cannot speak of we must be silent about. When Father did speak, he spoke so softly that even those who knew him well had to ask him to repeat himself. Once, during his Fulbright year in Egypt, when several of his students had discovered a crate of brass hearing trumpets for sale in the bazaar, they had carried these to class toat a prearranged signallift them simultaneously to their ears. (Yet, in sleep, Father ground his teeth so loudly my mother nightly dreamed of industry: gravel pits, cement factories, brickworks.)

I could add that Father was fastidious, sometimes changing his clothes two or three times a day. He ate little and dressed soberlyif with a specific, outdated flair: on formal occasions he wore a cummerbund. I took after him, played quietly by myself behind closed doors. And if Motherand she was a big, beautiful Icelanderwas a noisemaker, she made her noise out in the worldthe Officers Club, for example.

Father once admitted to me that chess saved him from losing his mindand this was said after he had lost his heart. When he played he became disembodieda mind on a stalk in a chair, invisibleand if he could keep ahead of his adversary, impalpable, too. In life as in chess, Father did not want to be touched, to be moved, to be seized; he was unwilling to be pinned down or cornered. He jumped from one discourse to another, embracing peculiar and obscure concepts and ideologies about which no one else knew anything; meaningful conversation with him proved an impossibility. In those years chess became the sole vehicle by which he could be reached, or rather, engagedfor he could never be reachedthe navigable airspace in which he functioned was invariably at the absolute altitude of his choosing. When he embraced the cryptic vocabulary of Coptic gnosticism, he lost his few remaining friends because it was impossible to follow the direction of his thoughts, and that was exactly what he wanted.

In Cairo Father played chess blindfolded and invariably he won. The positions of the pieces on the board were sharper in his minds eye than the furniture of his own living room (where he was constantly scraping his shins and knocking over chairs).

But I keep digressing. What I wish to write about is a brief period of time in Egypt, one year that seems to stretch to infinity, a year in limbo, a time of disquiet and loneliness. That year was a paradoxboth intensely felt and numbing. The world passed before my eyes like an animated stagedistant, colorful, unattainableand I, in my own little chair, looked on, watchful and amazed, frightened, enchanted, and disembodied, too.

In Egypt, Father had taken to wearing a fez to wander as unobtrusively as possible. He looked Egyptianwe both didso that Cairo embraced us unquestioningly, my fathers limited but convincing Arabic sufficing during brief encounters with beggars and merchants and dragomen; and he spoke French.

One winters day on an excursion to the Mouski, we passed the window of an ivory carvers shop, which contained any number of charming miniatures: gazelles, tigers, monkeys, elephants, and the like. As he gazed at the animalsand I supposed that he might elect to buy me oneFather began to cough and hum in a familiar way that meant he was about to make a brilliant move, or was excited by an idea. At that instant a small boy invited us into the shop and offered us two little chairs on which to sit. The carver appeared then, beaming, and sent the boy off to fetch coffee. The tray set before us, the mystery of Fathers excitement was revealed: If Father provided the drawings, could the carver make for him a chess set in which the goddesses and gods of the Egyptians and the Romans met face-to-face? Isis and Osiris, Horus and Amon Ra battling Jupiter and Juno and Neptune and Mars? Might sacred bulls confront elephants? He imagined the Egyptian pawns as ibises and the Roman pawns as archers.

Next page