Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To W. S. C.

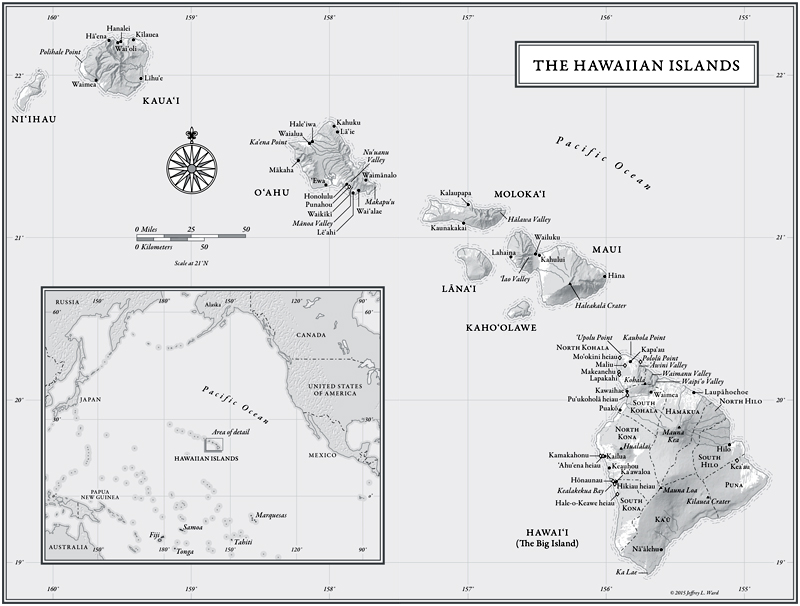

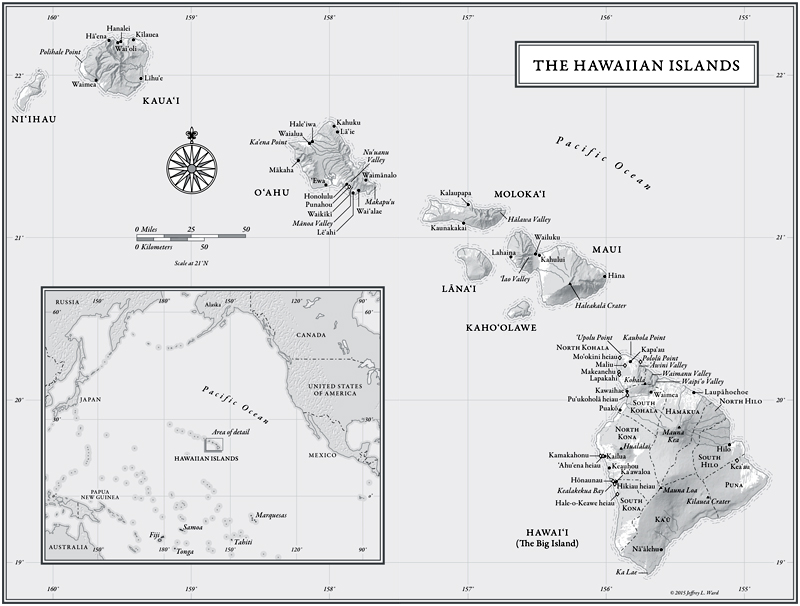

Five hundred thousand years ago, the great volcanoes of the easternmost island of Hawaii, among them Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea, and Huallai, rose eighteen thousand feet above the floor of the northern Pacific Ocean, breaking the surface in successive eruptions and outpourings of lava. Volcanoes still remain active on the Big Island, the last of the eight major Hawaiian Islands to rise from the bottom of the ocean (the islands of Kauai and Oahu are thought to have been formed ten million years ago). Moving from west to east, we find Niihau and Kauai; Oahu, the capital island; Molokai; Lnai; Kahoolawe; Maui; and Hawaii, with a combined area of 6,424 square miles (including the numerous uninhabited Leeward Islands, submerged seamounts, and atolls stretching 1,600 miles to Kure Atoll in the northwest).

At first and for a very long time, there was nothing but lava. The following was told to the anthropologist Martha Beckwith in the early twentieth century by J. M. Poepoe, a lawyer, legislator, and editor of the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka Nai Aupini :

This was the beginning of the earth It was an insect that made the coral and all things in the sea. This was the beginning of the period called the first interval of time. During this time grew the coral, the shellfish (such as the sea cucumber, the small sea urchin, the flat sea urchin, tiny mussels, the oysterlike mussel, the mussels of the sea, the clam, the barnacle, the dark sea snail, the cowry and so forth) The water was made to be a nest that gave birth and bore all things in the womb of the deep.

Over millennia, plants and seeds found their way to the Islands, washed ashore with the spring tide of a full moon, blown by trade winds, carried inside birds or in their feathers, in the trunks and branches of trees, and floating in the jetsam of sunken ships. The chance of a seed or sapling reaching an island as isolated as one of the Hawaiian chain (a combined area of 6,424 square miles, including the numerous uninhabited Leeward Islands, and atolls stretching 1,600 miles to the northwest) is infinitesimal. If it managed to survive its unlikely journey, there remained the still greater difficulty of finding what biologists call a niche. A prerequisite of its survival (and the same would be true for some of the first human settlers) would have been the ability to survive on hard, dry lava or in sand. With time, those species that managed to grow were able to provide shade and food to less vigorous species that followed them.

Indeed it is hypothesized that such an event occurred nearly 300 times during the history of the archipelago. Dividing this number into the number of years available in which such natural introductions could have occurred leads to the conclusion that, on average, one successful introduction need have occurred once every 20,00030,000 years If one takes 70 million years as the life of the entire archipelago such an event need not have occurred more than once every 250,000 years.

In other words, not very often.

The first stanza of a birth chant for Kauikeaouli, who would become King Kamehameha III in 1824, refers to the spreading of the powerful Kamehameha dynasty, but also serves as a description of the birth of the Islands:

Born was the earth, rooted the earth.

The root crept forth, rootlets of the earth.

Royal rootlets spread their way through the earth to hold firm.

Down too went the taproot, creaking

like the mainpost of a house, and the earth moved.

Cliffs rose upon the earth, the earth lay widespread:

a standing earth, a sitting earth was the earth,

a swaying earth, a solid earth was the earth.

The earth lay below, from below the earth rose.

* * *

In the spring of 1823, after a journey from New Haven of 158 days, the Reverend Charles Stewart, his wife, and their companion, the black missionary Betsy Stockton (who had once been a servant in the household of the president of Princeton University), along with fellow Congregationalist missionaries in the Second Company from Boston, watched from the brig Thames as it tacked along the north coast of the island of Hawaii. The broad base covered with Egyptian darkness, came peering through the gloom, wrote Stewart in his journal. The reality was too certain to admit a moments question; and was accompanied by sensations never known before The first tumult quickly succeeded by something that insensibly led to solemnity and silence.

Canoes of natives pulled alongside the brig, and the excited Stewart, who would become an astute and even sympathetic observer, had his first view of the men he and his brother ministers and lay teachers had come to baptize in the name of the Lord:

Their naked figures, and wild expression of countenance, their black hair streaming in the wind as they hurried the canoe over the water with all the eager action and muscular power of savages, their rapid and unintelligible exclamations, and whole exhibition of uncivilized character, gave to them the appearance of being half-man and half-beast.

A boat was sent ashore, and, when it returned, a ships officer sternly advised the missionaries to remain on board the Thames . If I never before saw brutes in the shape of men , I have seen them this morning. You can never live among such a people as this , we shall be obliged to take you back with us!

Stewart was alarmed. He wrote, Can they be mencan they be women?do they not form a link in creation, connecting man with the brute ? The missionaries did not heed the officers warninghow could they, after the great distance they had traveled and the avowals they had made?but instead disembarked, confused and alarmed. Stewart was to remain so for some time.

* * *

There is still dispute and controversy as to the identity and origin of the first human settlers in the Hawaiian Islands, although most scholars agree that the initial voyagers sailed from distant islands, known by Polynesians as Kahiki, in the South Pacific, most likely the Marquesas. Around 1200 B.C. , the farmers and fishermen who had migrated over centuries from Asia to Australia, Indonesia, and New Guinea began to move slowly across the Pacific, sailing to Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa, which lie only a few days sail from one another, where they became the ancestors of present-day Polynesians. After almost two thousand years, the islanders began to venture farther, eventually reaching Hawaii to the north, New Zealand to the southwest, and remote Easter Island to the east.

Historians once believed that many of the islands in the Pacific were discovered by fishermen who had been blown off course, although the fact that the first voyagers to Hawaii carried with them crops, seeds, and animals, as well as women and children, suggests that some of the journeys were deliberate and well-prepared. Abraham Fornander, a historian who was a circuit judge on the island of Maui in the late nineteenth century, believed that the first settlers arrived in the sixth century A.D. in what would become the Hawaiian Islands, and lived secluded and isolated for twelve to fourteen generations until the beginning of the eleventh century, when Polynesian folklore, legends, and chants attest a second migration of voyagers who made the journey north from Tahiti, a distance of 2,626 miles.