CRITICAL STUDIES IN NATIVE HISTORY

Jarvis Brownlie, Series Editor

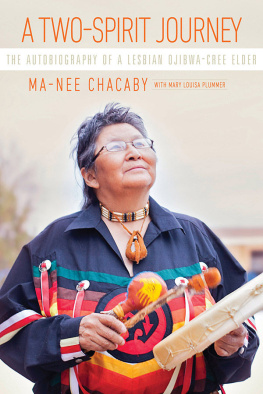

A TWO-SPIRIT JOURNEY

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A LESBIAN OJIBWA-CREE ELDER

MA-NEE CHACABY

WITH MARY LOUISA PLUMMER

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

Ma-Nee Chacaby and Mary Louisa Plummer 2016

Printed in Canada

20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

Cover and interior design: Jess Koroscil

Cover photo: by Ruth Kivilahti, www.ruthlessimages.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Chacaby, Ma-Nee, 1950, author

A two-spirit journey : the autobiography of a lesbian Ojibwa-Cree elder / Ma-Nee Chacaby with Mary Louisa Plummer.

(Critical studies in Native history ; 18)

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-88755-812-2 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88755-505-3 (pdf )

ISBN 978-0-88755-503-9 (epub)

1. Chacaby, Ma-Nee, 1950. 2. LesbiansOntarioThunder Bay Biography. 3. Elders (Native peoples)OntarioThunder BayBiography. 4. Ojibwa IndiansOntarioThunder BayBiography. 5. Cree Indians OntarioThunder BayBiography. 6. Thunder Bay (Ont.)Biography. I. Plummer, Mary Louisa, author II. Title. III. Series: Critical studies in Native history ; 18

HQ75.4.C53A3 2016 306.7663092 C2015-908010-X

C2015-908011-8

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

Ma-Nee Chacaby uses the terms Anishinaabe to refer to an Indigenous person and Anishinaabeg to refer to all Indigenous Peoples. In the text, Anishinaabe is also used as an adjective (Indigenous) to describe other nouns, e.g., Anishinaabe medicine, Anishinaabe family, or Anishinaabe history. The Anishinaabe words she uses in this book are Ojibwe. The spellings of Anishinaabe terms were generally standardized with existing dictionaries, except in cases where they did not reflect Ma-Nees pronunciation or knowledge of them.

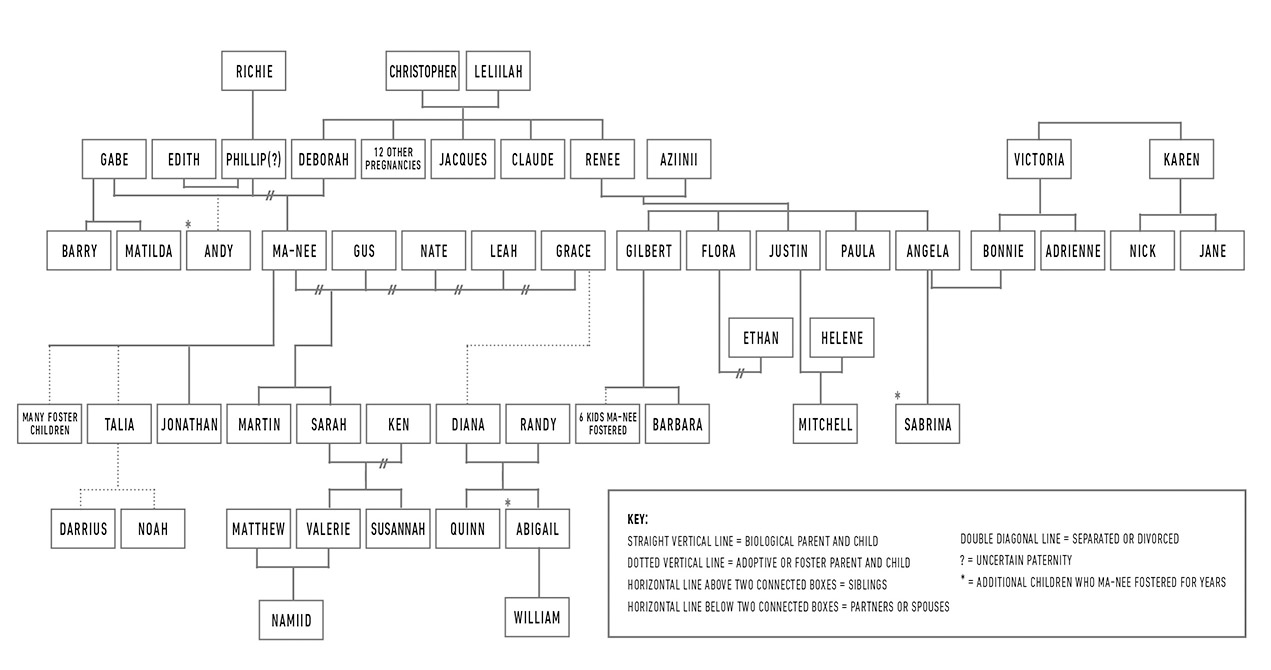

FIGURE 1. PARTIAL FAMILY TREE.

THIS DIAGRAM DEPICTS A PORTION OF MA-NEE CHACABYS FAMILY TREE AS OF DECEMBER 2013. FOR THE SAKE OF SIMPLICITY, ONLY INDIVIDUALS WHO ARE NAMED IN THE BOOK ARE INCLUDED. MANY OTHER BRANCHES IN THE TREE (E.G., SIBLINGS, COUSINS) ARE NOT DEPICTED.

To protect the privacy and the identities of the individuals mentioned in this book, all names, excluding Ma-Nees, have been substituted with pseudonyms.

CHAPTER ONE

MY GRANDMOTHERS AND MY FAMILYS HISTORY IN MANITOBA AND ONTARIO (18631952)

My name is Ma-Nee Chacaby. I am an Ojibwa-Cree elder, and I have both a male and a female spirit inside of me. I have experienced a long, complicated, and sometimes challenging journey over the course of my life. My earliest memories are of gathering kindling, making snowshoes, and hunting and trapping in my isolated Canadian community, where alcoholism was widespread in the 1950s. In 2013, more than half a century later, I performed a healing ceremony and then helped lead the first gay pride parade in my city, Thunder Bay, Ontario. This book describes the extraordinary path that led me to this place.

I will begin with what I have been told about my family history (Figure 1). Almost everything I know about the period before I was born I learned from my kokum (grandmother), who raised me. She was a Cree woman named Leliilah. She had a very long life and was the oldest among the elders in my Ojibwa-Cree community. When my grandmother died in 1967, her doctors guessed that she was over 100 years old. They entered her age as 104 on her death certificate, which means she would have been born in 1863. Some of the elders in our community later discussed the events in my grandmothers lifetime, and they agreed that she probably was born in the 1860s.

When I was a child, my kokum was well known as a storyteller in our community. Some of the following stories she told to me alone. Many I heard at social events, when other adults and children also gathered around to hear her tales.

MY GRANDMOTHERS CHILDHOOD

My grandmother came from the prairies of Saskatchewan. She lost her parents when she was a small child, maybe four or five years old. She remembered living with them and other families in teepees on a hill or a cliff that overlooked a sandy, broad river. My kokum said her community was in conflict with another Native group in the area. She said the other group did not have enough young people to have babies, so they wanted to kidnap children from her community. Because of that dispute, she and other children had been warned that, if their homes were ever attacked, they must run and hide under a canoe at a certain spot, some distance away.

My kokum explained to me that one night her parents woke her in a rush and told her to hide. She and her brother and another child ran to the canoe and crawled under it. They heard yells and screams from their homes, but they stayed quiet for a very long time, until there was silence. Then they waited even longer, as long as they could. They came out from under the canoe in the morning. The air was filled with smoke, and the teepees had been burnt to the ground. Dead bodies lay everywhere. The children were terrified and hid under the canoe again. In the end, they were discovered by travelling Cree families that were canoeing by the area. My grandmother said that those adults buried the dead in a large mound, and then adopted her and the other two children into their own families.

My grandmothers adoptive parents were very good to her. She and her brother were raised in different households within the same extended family. Their new family had also been attacked by another Native group in their original home, so they were migrating across Canada, trying to reach relatives on the coast of James Bay, in northern Ontario. For many years my grandmother travelled with them by foot, horse, or canoe in summer, and dogsled and horse in winter. She said they moved faster on ice and snow, trapping and hunting animals as they travelled. My kokums strongest memories of those years were of bitterly cold winds that chilled her as she slept in a teepee at night. While they journeyed, she also saw a branch of the Hudsons Bay Company store when she was about ten or eleven years old. The store was on a boat that moved from place to place to sell its wares. In that store, my grandmother saw a mirror for the first time. She also tasted her first orange, which she remembered as being both sweet and sour.

My grandmother and her family must have travelled about 1,500 kilometres as they moved eastward along a northern route that crossed both Manitoba and Ontario. They only created a permanent home when they reached the Attawapiskat River on James Bay (Figure 2) in the early 1880s, when Leliilah was ten or eleven years old.

Next page