The Ojibwa Dance Drum

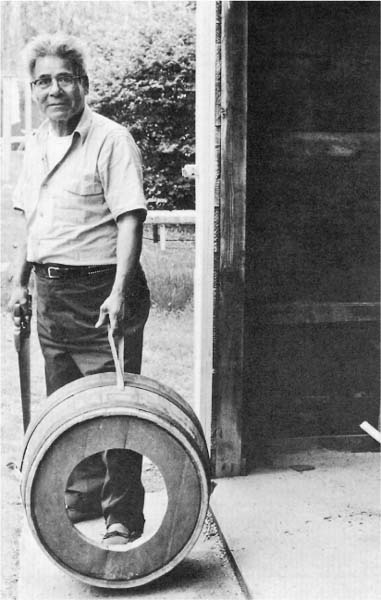

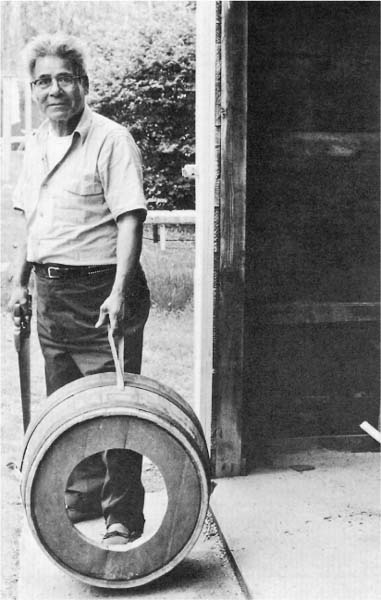

William Bineshi Baker, Sr., Ojibwa drummaker from Lac Court Oreilles Reservation, Wisconsin, with completed drum frame ready to receive its rawhide drumheads. (Photo by N. T. Wheelwright, 1970.)

The Ojibwa Dance Drum

Its History and Construction

Thomas Vennum

With a new afterword by Rick St. Germaine

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

New material 2009 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

Originally Published in the United States by the Smithsonian Institution Press in 1982.

www.mhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-87351-642-6 (paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87351-642-7 (paper)

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vennum, Thomas.

The Ojibwa dance drum : its history and construction / Thomas Vennum ; with a new afterword by Rick St. Germaine.

p. cm.

Originally published: Washington, D.C.

: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87351-642-6

(pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87351-642-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-87351-763-8

(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Drum.

2. Indians of North AmericaMusicHistory and criticism.

3. Ojibwa IndiansMusicHistory and criticism.

I. Title.

ML1035.V46 2009

786.921908997333dc22

2008046158

Contents

Editors Preface

In 1978 the Smithsonian Office of Folklife Programs established Smithsonian Folklife Studies to document, through monographs and films, folkways still practiced (or re-created through memory) in a variety of traditional cultures. Drawing on more than a decade of research accruing from fieldwork conducted for the Programs annual Festival of American Foklife, the studies are unique in that each consists of a monograph and a film, conceived to complement each other. The monographs present detailed histories and descriptions of folk technologies, customs, or events and include information about the background and character of the participants and processes through photographs (historical and contemporary), illustrations, and bibliographies. The films add a living dimension to the monographs by showing events in progress and traditions in practice, the narrative being provided mostly by the tradition bearers themselves. Thus, while each monograph is planned to permit its use independent of the film (and vice versa), their combined study should enhance the educational and documentary value of each.

Smithsonian Folklife Studies grew out of discussions begun as early as January 1967, when the Institution began plans to convene a group of cultural geographers, architectural historians, and European and American folklore scholars in July of that year. One recommendation of the conference stressed the need for new directions in documentation to keep pace with the ever-broadening scope of the discipline, as it extends from the once limited area of pure folklore research to encompass all aspects of folklife. It was proposed at the time that the Smithsonian establish model folklife studies, although no specific forms were prescribed. (The Festival was one form developed to meet this challenge.) The new publication program, therefore, makes available studies that approach earlier research from new perspectives or investigate areas of folklife previously unexplored.

The topics selected for the publications range widely from such traditional folklore interests as ballad singing to newer areas of concern such as occupational folklore. Included are studies of old ways in music, crafts, and food preparation still practiced in ethnic communities of the New World, centuries-old technologies still remembered by American Indians, and homemade utilitarian items still preferred to their store-bought counterparts.

Nearly all these traditions have been transmitted orally or absorbed through repeated observations. Several generations of Meaders family sons, for instance, began to learn pottery-making while at play around their fathers shops. Because words cannot always communicate, apprentices must be shown the technique.

Many of the activities documented in the Smithsonian Folklife Studies, however, are practiced in a world apart from that of the factory; therefore, by modern standards of mass production, the technologies shown may seem inefficient and imprecise. In some of them, the proportions used, arrived at through years of trial and error, are often inexact (viz., Cheevers recipe for ash glaze, roughly two churns of settlins to three of ashes or his recipe for lime glaze, which differs from his wifes recipe) or measured by using the human hand as does Paiute craftswoman Wuzzie George when she spaces the bindings on her duck decoys. It is also a world in which the craftsman eschews technical terminology, preferring instead to attach names to his products that relate them to resemblances elsewhere, where a southern folk potter describes his kiln as a railroad tunnel or ground hog, or an Ojibwa Indian refers to the cloth tabs decorating the sides of his traditional drum as earflaps.

Many traditions presented in the Studies date to times when the pace of work and passage of time were relatively unimportant. It was an age when Cheever could spend hours grinding his clay with a mule-drawn pug mill (I just like it that way) and William Baker could take pride in stitching by hand every inch of the several layers of cloth decorating his drum (I could use a sewing machine, but Id rather use my own handpower. You wont see anything on my drum made by machine.) Deliberateness is often commensurate with accomplishment, and, for the folk potter and Indian drummaker, quality in their products results from the care and time devoted to their manufacture.

The decline of many folklife traditions has paralleled the general social breakdown of communities, in many instances the result of advances in technology. Concurrent with this social dissolution has been the disappearance of many utilitarian items that the maker traditionally created for himself or his family. When commercially produced glassware appeared for home canning, it doomed to eventual extinction the churns and jugs that Cheever Meaders, the farmer/potter, had turned and fired for use by his wife and neighbors in making butter or pickling meat and vegetables. The closing of Nevada marshlands to Paiute Indians forced them to depend on food supplies from white trading stores. This precluded the need for Wuzzie George to weave from tule reeds small bags in which to collect duck eggs, a staple of generations before her. Or, as drummaker Bill Baker laments, todays Ojibwa singers find it expedient to purchase marching-band drums from music stores for their dances, thus marking the passing of the former practice of his people to construct a dance drum as a communal activity in which all took pride.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.