Copyright 2017 by Damion Searls

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Hogrefe Verlag Bern for permission to translate the essay Leben und Wesensart by Olga Rorschach, from Gesammelte Aufstze, Verlag Hans Huber, Bern, 1965. All rights reserved. Used with kind permission of the Hogrefe Verlag Bern.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Searls, Damion, author.

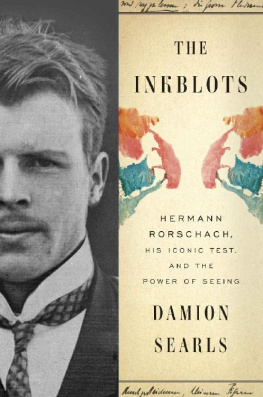

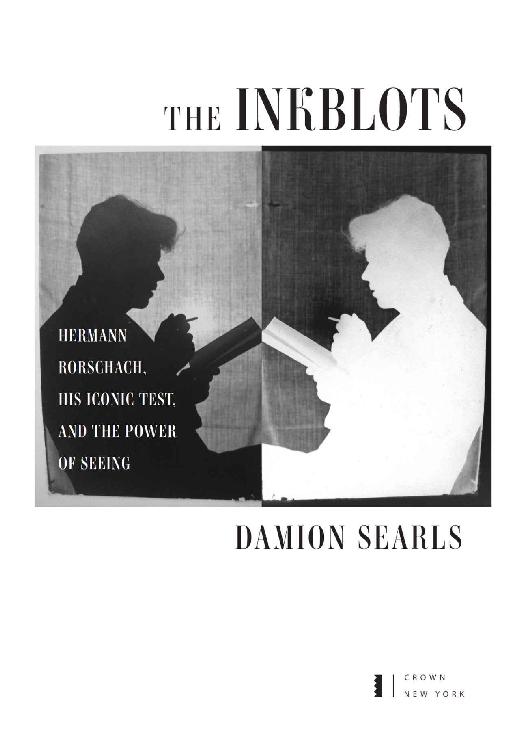

Title: The inkblots : Hermann Rorschach, his iconic test, and the power of seeing / Damion Searls.

Description: New York : Crown Publishing, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028995 (print) | LCCN 2016042118 (ebook) | ISBN 9780804136549 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780804136563 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780804136556 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Rorschach, Hermann, 18841922. | PsychiatristsSwitzerland. | Rorschach Test.

Classification: LCC RC438.6.R667 S43 2017 (print) | LCC RC438.6.R667 (ebook) | DDC 616.890092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028995

ISBN9780804136549

Ebook ISBN9780804136556

Cover design: Elena Giavaldi

Cover photographs: (inkblot) Spencer Grant/Science Source/Getty Images; (Rorschach and handwriting) Archiv und Sammlung Hermann Rorschach, University Library of Bern, Switzerland

v4.1_r1

a

The soul of the mind requires marvelously little to make it produce all that it envisages and employ all its reserve forces in order to be itself.A few drops of ink and a sheet of paper, as material allowing for the accumulation and co-ordination of moments and acts, are enough.

P AUL V ALRY , Degas Dance Drawing

In Eternity All is Vision.

W ILLIAM B LAKE

T he Rorschach test uses ten and only ten inkblots, originally created by Hermann Rorschach and reproduced on cardboard cards. Whatever else they are, they are probably the ten most interpreted and analyzed paintings of the twentieth century. Millions of people have been shown the real cards; most of the rest of us have seen versions of the inkblots in advertising, fashion, or art. The blots are everywhereand at the same time a closely guarded secret.

The Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association requires that psychologists keep test materials secure. Many psychologists who use the Rorschach feel that revealing the images ruins the test, even harms the general public by depriving it of a valuable diagnostic technique. Most of the Rorschach blots we see in everyday life are imitations or remakes, in deference to the psychology community. Even in academic articles or museum exhibitions, the blots are usually reproduced in outline, blurred, or modified to reveal something about the images but not everything.

The publisher of this book and I had to decide whether or not to reproduce the real inkblots: which choice would be most respectful to clinical psychologists, potential patients, and readers. There is no clear consensus among Rorschach researchersabout almost anything to do with the testbut the manual for the most state-of-the-art Rorschach testing system in use today states that simply having previous exposure to the inkblots does not compromise an assessment. In any case, the question is largely moot now that the images are out of copyright and up on the internet. They are easily available alreadya fact that many of the psychologists opposed to publicizing the images seem to want to ignore. We eventually chose to include some of the inkblots in this book, but not all.

It has to be emphasized, though, that seeing the images reproduced onlineor hereis not the same as taking the actual test. The size of the cards matters (about 9.5 6.5), the white space, the horizontal format, the fact that you can hold them in your hand and turn them around. The situation matters: the experience of taking a test with real stakes, having to say your answers out loud to someone you either trust or dont trust. And the test is too subtle and technical to score without extensive training. There is no Do-It-Yourself Rorschach, and you cant try it out on a friend, even apart from the ethical problem of possibly discovering sides of their personality that they may not want to reveal.

It has always been tempting to use the inkblots as a parlor game. But every expert on the test since Rorschach himself has insisted it isnt one. Theyre right. The reverse is true, too: the parlor game, online or elsewhere, is not the test. You can see for yourself how the inkblots look, but you cant, on your own, feel how they work.

had reached the final round of applying for a job working with young children, but, this being America at the turn of the twenty-first century, he still had to undergo a psychological evaluation. Over two long November afternoons, he spent eight hours at the office of Caroline Hill, an assessment psychologist working in Chicago.

Norris had seemed an ideal candidate in interviews, charming and friendly with a suitable rsum and unimpeachable references. Hill liked him. His scores were normal to high on the cognitive tests she gave him, including an IQ well above average. On the most common personality test in America, a series of 567 yes-or-no questions called the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI, he was cooperative and in good spirits. Those results, too, came back normal.

When Hill showed him a series of pictures with no captions and asked him to tell her a story about what was happening in each oneanother standard assessment called the Thematic Apperception Test, or TATNorris gave answers that were a bit obvious, but harmless enough. The stories were pleasant, with no inappropriate ideas, and he had no anxiety or other signs of discomfort in the telling.

As early Chicago darkness set in at the end of the second afternoon, Hill asked Norris to move from the desk to a low chair near the couch in her office. She pulled her chair in front of his, took out a yellow legal pad and a thick folder, and handed him, one by one, a series of ten cardboard cards from the folder, each with a symmetrical blot on it. As she handed him each card, she said: What might this be? or What do you see?