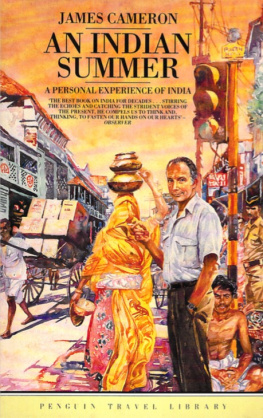

An Indian Summer

James Cameron started his lifelong career in journalism in Dundee in 1928. After leaving Scotland he travelled widely as a foreign correspondent in almost every part of the world, working for Picture Post and the ill-fated News Chronicle before becoming a freelance.

He won the Granada Journalist of the Year Award and Foreign Correspondent of the Decade A ward for his journalism, and he moved on to television journalism in the 1970s.

James Cameron, who wrote several other books, including Point of Departure, died in 1985. The Observer said of his work: There are very few journalists capable of the precise combination of topicality, experience and controlled indignation which make up his best pieces. The Times, writing about An Indian Summer, described it as The diary of a year in the life of a sharp and sensitive man spent in various Indian settings Delightful pages that evoke everything of the odd pattern of human behaviour under the Indian sun. The Times of India was equally complimentary: Few foreigners are so well qualified to write a book on India It is no exaggeration to say that he is in love with this vast, complex, confusing and often tormenting country.

From the fourth cover

Both a stunning evocation of India and a personal memoir at once entertaining, enlightening and affecting - The New York Times

In 1972 James Cameron , newly married to an Indian, returned to India. a country he had known since before the end of the Raj. It was a land with which he was already deeply in love - at once exasperating, generous beautiful and corrupt.

When he describes the sounds and smells and characters and inevitable encounters of India he is unparalleled It is his ability to come to term with India seething confusion which makes the descriptive passage required reading for a newcomer to the country - The Times Literary Supplement

An Indian Summer will take its place among the classics of Anglo-Indian literature, and will be returned to again and again by those whom it has captivated or enraged and finally overwhelmed with such a flood of human compassion, and tragic sense, and comic inspiration -Standard

Extraordinarily rich, packed with treasures of description, of reflection, of introspection -a book which will teach outsiders a lot about India (which is difficult) and Indian something about themselves (which is even more difficult).The writing is superb - Dervla Murphy

To me this book is pure joy India is a country of great dignity and human frailty and this is the best book on the country and its people that I have read for 20 years -Spectator

By the same author

TOUCH OF THE SUN

MANDARIN RED

1916, WITNESS

1914, THE AFRICAN REVOLUTION

POINT OF DEPARTURE

WHAT A WAY TO RUN THE TRIBE (Selected journalism)

JAMES CAMERON

An Indian Summer

This was originally conceived more than three years ago as a book about India, which I have known and perversely loved for a long time. I had a feeling even then that there had been more than enough books about India.

By the time I began, however, I was married to an Indian; it produced a wholly new dimension to the job and dispelled my doubts. It is in the book that if I were to seek pride in India now it would in a tiny way be part of my pride; if there were to be disappointment and regret I must now share that regret, and in some oblique way accept its responsibility.

In this book I have said things which may sound critical, wounding. even angry. In expiation I can say that I have been as bitter about many societies, including my own. I do not mean to be hurtful to a warm and generous people who have never been other than kind to me; wherein I have seen things cruel and hostile it is because they are cruel and hostile to India itself. Only now, after twentyfive years of knowing India, can I make the presumption of claiming a small share both in its rare joys and its frequent sorrows.

But of course that last Indian Summer was not allowed to be enough. The Bangladesh episode intervened. Foolishly, perhaps, I went up to pry; I was badly injured on the Border. I spent a long time in hospitals in London, where a pretty full and exacting life at last caught up with me and sent me into the strange realms of profound heart-surgery, and the strangely changed world that follows it.

There are after all two meanings to An Indian Summer, and by and by for me they merged into one.

This is why I dedicate this book to an Indian.

TO MONI

who gave me her hearts blood, and my lifes hope

1

I had seen the collision coming, but when it happened the impact was so abrupt and stunning that it shocked the sense out of me, and for a while I sat quietly among the broken glass of the jeep as though I had been sitting there forever. In any case I found I could not move because of the dead weight of the soldiers on either side of me. We had hit the bus head-on. The front of the jeep was embedded under its bonnet, and the crash must have somehow distorted the wiring apparatus because the first thing I became aware of was a continuous metallic howl from the horn that nobody tried to stop. It seemed as though the machinery itself was screaming in pain, while all the people involved were spellbound and silent.

The first rains of the monsoon were streaking vertically out of the low grey sky like a curtain, and through the cataract along the roadside came the procession of refugees: gaunt, drenched, wordless, totally abstracted, driving their fatigue and apathy along in an interminable caravan through the soggy mud of the road into India. The rain was almost opaque. The Bengalis glanced without expression or wonder at the mangled wreckage of the jeep and the bus, but they did not pause nor question it; why should they ? They had been four or five days on the road from East Pakistan, hiding from the Punjabi soldiers from the West; they were now quite drained of emotion or response. We offered no threat; they offered no help. In my inertia it all seemed very reasonable. I felt I had been watching just such a frieze of refugees for the last twenty years, and I was just bewildered enough to have a momentary difficulty in recalling where I was - Germany, Palestine, Vietnam, even India itself, so long ago? Refugees are the last International.

This multitude was pouring out from what was not quite yet Bangladesh. Already some four or five million had crossed over, and still they were coming at the rate of about sixty thousand a day, ragged and silent, carrying on their backs their very young and very old, anaesthetised by exhaustion and despair. There was no noise, no complaint, no kind of tumult. Now, on their last lap to the camps, the rains were overwhelming them. Ten minutes earlier we had passed three babies drowned and abandoned in the few inches of rushing rainwater by the road.

Our small personal disaster was of no consequence to the Pakistanis now. I wondered how I was ever going to move again.

Some of the passengers from the stranded bus had climbed out and now stood grouped around . the wreck with the mute incurious Indian stare, doing nothing.

Suddenly the braying horn stopped, and then there was nothing to hear but the thudding rain.

Sitting there wedged in the front of the jeep I found at first that I could hardly stir. The driver to my left was apparently dead; the Colonel on my right seemed nearly so; they were both big and corpulent men and they lolled against me, jamming me between their khaki tunics and spilling blood into my lap. The Colonels face was a makeup of fantasy; he had been scalped, and as fast as the wound soaked him scarlet the rains washed away the blood and diluted it; the broken jeep stood in a red pool that turned pink and drained away into the mud.

After a while I dragged myself out from between the Colonel and the subhadar, but I found that I could not stand at all, and was obliged to sit against the back wheel in the sludge. The refugees walked slowly around me, patiently plodding west.

Next page