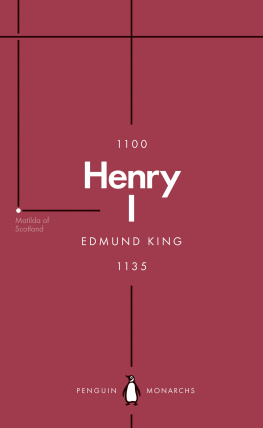

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

James Ross

Henry VI

A Good, Simple and Innocent Man

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2016

Copyright James Ross, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design by Pentagram

ISBN: 978-0-141-97935-9

Introduction

The Enigma of Henry VI

Few would disagree that Henry VI, son of Henry V and last king of the house of Lancaster, was one of the least able and least successful kings ever to rule England, although people continue to disagree, as they did during Henry VIs reign itself, about how and why this should have been so. Shakespeare, writing his history plays 150 years later, described Henrys England as a state of which so many had the managing, / That they lost France and made his England bleed. The great playwright thus neatly encapsulated the disasters of the loss of Henry Vs French conquest and the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses in the last few years of Henry VIs reign, while emphasizing the common perception that Henry was dominated by the personalities around him. Shakespeare was not incorrect, but both the king and his reign were considerably more complex.

Within a few years of Henry VIs final deposition from the English throne in 1471, two writers were confronting his legacy. Sir John Fortescue, one of Englands chief justices, the Lancastrian loyalist who disavowed his writings when he made his peace with Henrys Yorkist successor, King Edward IV, wrote a tract suggesting reforms to the In other words, Fortescue argued that, in restricting the kings power to impoverish himself, the king would become more powerful. Fortescues advice, cogent though it was, did not noticeably change Edwards style of kingship, though some of his ideas perhaps influenced Henry VIs nephew, Henry Tudor, when he took the throne in 1485.

Another contemporary of Henry VI, John Blacman, a fellow of Eton and Henrys former chaplain, wrote a detailed description of the king around a decade after his death. Blacman passed over the practical and conceptual problems of kingship that Henrys reign had thrown up, instead focusing on the kings personality and explaining his failings as an earthly monarch by implying that he led an exemplary religious life that was more in keeping with sainthood than kingship a picture that historians through the ages have been wary of accepting, given later, official, attempts to have Henry canonized as a saint. As these rather different attempts to understand him Blacmans positive spin on his failings, Fortescues suggested remedies for his errors show, Henry VI was and remains an enigma.

There is of course a further issue. It is difficult enough for biographers to grasp the personality and character of great figures of the twentieth or twenty-first centuries, despite the comparative abundance of private letters, diaries, public speeches, broadcasts or written works, and contemporary comments. It is far more difficult for medieval historians to grasp the personality and character of those living five hundred years before, even that of a king. Private records revealing innermost thoughts are very rare, governmental records noted acts carried out in the kings name as a matter of course without necessarily revealing the agency behind them, contemporary comments were likely to be after the event and with an axe to grind, and an individuals acts, though providing hints as to his or her motivations, are subject to interpretation.

Even in this context, Henry VIs character and personality are particularly elusive. Not only was he, in the eyes of many contemporaries and historians, a passive, introverted figure, but even the surviving documentary evidence on Henry is peculiarly open to question. For few other kings would we question so closely, and with some justification, whether the words written in his name were his own, whether the documents he signed or the acts he made as king were his or were inspired, manipulated or dictated by those around him, his wife, his leading ministers or his courtiers and household servants. For almost no other medieval figure is the evidence so lacking in authority.

The nature of the evidence explains why there has been such a variety of views among modern historians on Henrys character. The most devastating view was that of one of the greatest of late-medieval historians, K. B. McFarlane, writing in the 1930s, for whom in Henry, second childhood succeeded first without the usual interval.