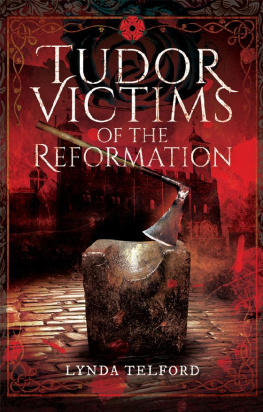

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. ( Bridgeman Images )

D uring the early 1470s, in the reign of King Edward IV, Robert and Joan Wolsey celebrated the birth of a son. We cannot be sure of the exact date on which this extraordinary child first saw the light of day, but that was common enough. Births often went unrecorded, or the records were subsequently lost. Historians vary slightly in their estimates of the appropriate date, ranging from the March of 1471 to the winter of 1472/3. The slightly earlier date was recommended to coincide with the feast date of St Thomas Aquinas on 7 March.

One of the many events considered to be prophetic was the appearance of a comet. At around the time of Wolseys birth a comet appeared in the sky over England. It was quite a large one, now known to have been a magnitude 4 (Halleys Comet is magnitude 7), so the event was easily seen and lasted for some time. It first appeared on 25 December 1471 and was clearly visible until 21 February 1472. For those readers with an interest in such phenomena, it is registered as C/1471-YI. Whether it was indeed to foretell unusual happenings ahead, or not, is open to interpretation.

The son born to Robert and Joan (ne Daundy) probably had no siblings, but it was obvious that, contrary to custom, this apparently gifted child could be spared from the family business. However, Robert aimed high for his son. The parents of this child were in a comfortable situation. The epithet often applied to Wolsey by detractors during his later life was son of an Ipswich butcher. However, the prosperous Robert Wolsey was actually rather more than that. The family had moved to Ipswich from Combe near Stowmarket. There was even at one time a suggestion that he had allowed his house to be used for immoral purposes, although no details are given.

However, despite a certain loss of good name, his machinations paid off. The family began to do very well, regardless of the difficulties still lingering from the effects of the catastrophic plague of the previous century. These were still evident in a lack of manpower, along with a new and disturbing line of thought among people who had realised that they finally had worth in the labour market. There were also echoes of remaining instability from the civil wars, which had taken King Edward IV to the throne. Great changes had come about since the Hundred Years War, which had also leeched England of manpower and prosperity. But change and upheaval was good for men such as Robert Wolsey. They were the very ones eager to grasp at any opportunity and were able to thrive on change which could bring them some advantage. Robert Wolsey was officially a grazier, making his living from sheep and cattle. By 1480 he was actually referred to as a squire by a monk of Ipswich, who spoke of the fat cattle he saw grazing on the lands of Maister Wolci.

Not only meat would be produced by such a livestock business, but also hides and other by-products, most particularly the all-important fleeces for the wool trade at Calais. Maister Wolci was obviously in a fair way to becoming comfortably well off.

Such people as these, rising in a world that opened new horizons, were the ones most likely to appreciate the benefits of good education. It must quickly have become obvious to the father of young Thomas that he had produced a boy of unusual intelligence, whose ability could be better used to further the familys good than merely to make another grazier out of him. Children were always considered a source of revenue in one way or another, but in this case there would be far more gained by sending him away to acquire a proper education.

By 1479 Robert Wolsey had purchased for 8 a certain amount of land, along with a house, near Rosemary Lane. It was a respectable address and close also to the Ipswich Grammar School, although by the age of 11 the young Thomas had already taken what he could from the educational facilities of Ipswich. He moved to Oxford, a good three years ahead of the usual time for finishing an education there. Peter Gwyn in The Kings Cardinal states that for a young man in Wolseys situation, given the new social and financial standing of his family, it would have been perfectly normal for him to expect to be sent to Oxford. He attended the new College of St Mary Magdalen. This was in the process of erection when he arrived, the foundation of Bishop William Waynflete. In the new colleges attempts were being made to compel the students to accept some form of discipline as well as regulate their otherwise very erratic learning patterns.

Thomas Wolsey was at Magdalen, moving towards his batchelors degree, in 1483 when King Edward IV died. This early and unexpected death was to lead to the further upheaval of the reign of King Richard III, after the marriage of the late king, his brother, had been declared bigamous and its offspring illegitimate. Richard III spent some of his first year of kingship moving around the country, culminating in a triumphant visit to York in August of 1483. However, we know that he also paid a visit to Oxford just prior to that, in July, using Magdalen College as his headquarters, and was honourably received there.

Wolsey would certainly have seen King Richard on that occasion. Did he have any premonition that he too was destined for great things? He was certainly a young man full of confidence, willing to take chances, proud of his achievements, so he may have been determined to make something of himself, quite apart from the expectations of business and modest prosperity.

Richard IIIs brief reign was to come to an untimely end due to the Tudor claimant and his ferocious mother Margaret Beaufort, but during his term of kingship Richard did make genuine attempts to bring order to the country. In many parts, including the north where he was known and respected, there was grief and resentment at his passing. This feeling was to make the throne uncomfortable for his successor in the years to come. Although these upheavals need not have concerned Thomas Wolsey, he would by that time have been casting his eyes towards his future prospects.

His own testimony tells us that he received his degree at the age of fifteen years, which was a rare thing, and seldom seen! (the usual age was 17). The ceremony during which the degree was actually attained was a difficult one and known as a determiner. This involved the student standing, for nine days, being obliged to defend his level of learning against all comers. This gave an opportunity to show off the oratorical skills of the student, his ability to work a crowd and sway opinions, in something akin to the old Roman tradition of rhetoric. It must have been stressful, but when successful also uplifting, and was accepted as being the high point of any young mans college career.

Wolsey remained at college and later became a Fellow of Magdalen. He also earned for himself the title of boy bachelor in reference to his scholastic achievements at such a young age.

While Thomas was advancing in his studies, his father was advancing also. He had bought another house in the south ward of the town. He was still often at odds with the authorities, due to his dubious methods of conducting business, but on the whole such problems were small and did him no real harm. He began to enjoy a different sort of reputation in the Parish of St Nicholas, one of respectability and social acceptance, no doubt greatly bolstered by his now substantial income. He had moved quite rapidly into the emergent merchant and business class. These people, though without any claims to gentle birth or good family connections, could still find themselves in a position to gather serious wealth, and even helped to finance the enterprises of their social superiors. Any merchant who had the shrewdness to see openings in the new markets would have realised the good sense in producing cloth at home, from the fleeces of his own flocks. Rather than sending bales of fleeces abroad, as was the custom formerly, it was by then increasingly effective to export the finished woollen cloth. By managing the whole process in this way, it showed not only an eye for the main chance, but also the ability to read the changes in the wind prevalent throughout Europe. It was this concern for market forces and the accompanying willingness to adapt that was to produce the great merchant princes of the future.