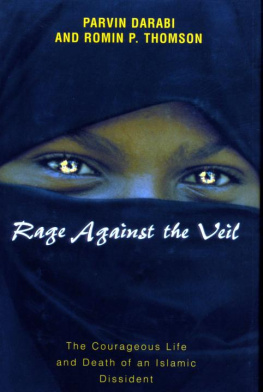

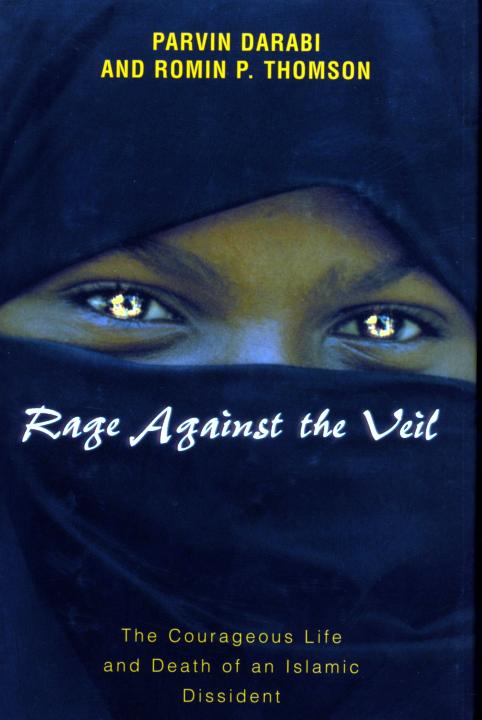

PARVIN DARABI AND ROMIN P. THOMSON

For Homa.

How happy is a bird who has never seen a cage? Even happier is the one who has fled the cage. They have broken our wings and opened the doors of the cage.

-Sadegh Sarmad

The authors wish to thank Helmut Feller for his contributions and expert advice. Likewise sincere thanks are extended to the late Gustav Luebbe, Anja Kleinlein and Peter Molden without their encouragement this project would not have been realized. Our gratitude includes Betty Mahmoody, our relatives and friends, as well as Reiner D. Meier and we thank them for their assistance and that we have been allowed to stir up their memories with our questions.

To our mother and grandmother we would like to show our sincere respect and assure her of our deep understanding of her ordeal and its circumstances. We share with her the grief of Homa's too early departure.

February 22, 1994

When my uncle Hossain called from Iran to tell me what had happened, my sister had already been buried. It was early and the phone woke me. Half asleep, I picked up the receiver and heard his voice tremble.

"Parvin?"

"Hossain, what is it?"

"Sweetheart, it's Homa, she-" He wheezed softly and paused.

"What do you mean?!" I sat up quickly. "What's happened to Homa?! Is she all right?" I had been worried about her for several months. "Is she dead?!" I was screaming. Over the static, I heard him crying. I also heard my mother in the background. She was hysterical. They were bawling over the phone and I didn't understand why.

I was bracing myself for awful news. I knew my sister was very depressed and disappointed with her life in Iran. I feared the worst and kept asking my uncle, but he wouldn't stop crying. I was terrified and my heart sank when I tried to imagine what it could have been. I just kept asking, "Is she dead?! Is she dead?!"

Finally he gained his composure long enough to say "Yes." And then he began crying again.

As my head turned toward my husband, I started to cry. I felt myself sliding off the edge of the bed and falling down on the floor. I sat there, hunched over, holding the phone against my ear and my hand over my mouth. Tears rolled down my face and I felt paralyzed.

My uncle's voice broke repeatedly as he told me how Homa and my mother had spent the day together before she died. He told me they'd had lunch together at Homa's house. He said my mother was napping when Homa quietly left. She walked to her car and drove to the northern part of Tehran, an area called Tajrish.

My uncle fought to keep his composure between every word. "She must have stopped somewhere to buy the gasoline," he said.

"I don't understand!" I wasn't thinking. I had no idea.

"Oh sweetheart! It's awful. I don't want to tell you. It's your sister; it shouldn't be this way!"

"What happened to her?!"

He didn't answer me for a while. He only wept. I could tell he was trying to explain, but each time he started to speak his voice would cripple and he would cry more. It was hard to listen to him. He sounded helpless.

"Just wait," I told him. "I'll wait for you. You can tell me when you're ready."

He cried a while longer and finally caught his breath long enough to explain. "Sweetheart, your sister drove to Tajrish. She went there with the gasoline and she burned herself. She burned in front of hundreds of people. She burned like that-with everyone watching."

I heard him, but I struggled to comprehend the things he was telling me. It was as though he was speaking too quickly for me to hear the words. As he spoke, what he was telling me would sink in, and then the horrible sadness I felt would overcome me and I wouldn't be able to hear him anymore. The realization of what he was telling me fell onto me in waves of immense pain.

I couldn't listen anymore. When he called, I only wanted to know if she was dead. That, to me, was the worst-case scenario. I thought there would be nothing that he could say to me about my sister that could be more awful. I was naive.

I asked to talk to my mother. She came on the line and her voice was hoarse. I could tell she'd been crying for a long time. She was devastated. She couldn't speak without sobbing and she only repeated the same phrases. All she could talk about was being with Homa in the morning, before she killed herself. She kept telling me about their lunch and how Homa seemed relaxed while they ate together. But when she woke from her nap, she worried because she couldn't find Homa in the house.

Then she cried and told me about all the places she had called to try and find her. She said Homa's husband called in the evening. As she continued, her voice grew louder and she continued to weep. She said she'd rushed quickly to get to the hospital, but by the time she arrived the doctors had already given up on Homa.

She told this story several times and I couldn't stop her. I only listened and waited for her to calm down. When she was too grieved to continue, she gave the phone to my grandmother, who seemed to be suffering even more. Grandma cried and told me about having been proud to reach the age of eighty-six without ever burying a child or a grandchild. I tried to comfort her, but there was little I could do from so far away.

I listened for a while longer and then I put the phone down. It was an awful moment. I felt a tremendous sadness within me. My husband was awakened by the conversation and he wanted to know what happened. I told him, and as I talked, the depth of the tragedy began to unfold. I started to realize that my sister was gone forever. The pain grew and I cried violently. He was also upset, but he didn't say anything. He looked after me for the rest of the morning.

The news of my sister's death was a tremendous shock. She had been one of the most prominent child psychiatrists in Iran. She was married and had brought two successful, ambitious daughters into the world. She was licensed to practice medicine in Iran, and in forty-nine states in the United States.

She was the first Iranian ever to be accepted to the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. She established the first clinic in Iran dedicated to treating children suffering from mental disorders that, until then, were thought to be incurable. She quickly established herself as a premier psychiatrist in Iran. She taught at the University of Tehran, worked at its hospital, and managed her own private practice.