Witchfinders

A Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy

MALCOLM GASKILL

www.johnmurray.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK Company

Malcolm Gaskill 2005

The right of Malcolm Gaskill to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN: 9781444726923

Book ISBN: 9780719561213

John Murray (Publishers)

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.johnmurray.co.uk

Contents

In memory of Stephen Williams

19671993

who understood well the strangeness of the past

Also by Malcolm Gaskill

Crime and Mentalities in Early Modern England (2000)

Hellish Nell: Last of Britains Witches (2001)

Bear in mind that man is but a devil weakly fettered by some generous beliefs and impositions.

Robert Louis Stevenson

Every tragedy falls into two parts: complication and unravelling By the complication I mean all that extends from the beginning of the action to the part which marks the turning-point to good or bad fortune. The unravelling is that which extends from the beginning of the change to the end.

Aristotle

Illustrations

For full details of sources and permissions information, see

Preface

In seventeenth-century England people inhabited a magical universe, a cosmos full of spiritual and occult forces with the power to shape earthly events. Not everyone adhered to exactly the same beliefs, nor was there consensus about meaning. And yet a time-traveller would be astonished by the vigorous currents of supernatural thought common to men and women at every social level, from the hub of the metropolis to the darkest corners of the land. Barely fifteen generations ago, England was a God-fearing but by modern standards superstitious nation, where rivers of Christianity and pagan folklore flowed into one another. The past is always a foreign country, but at times it can feel like an alien world.

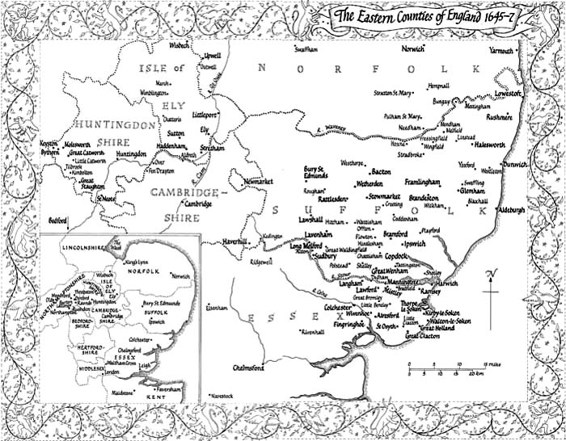

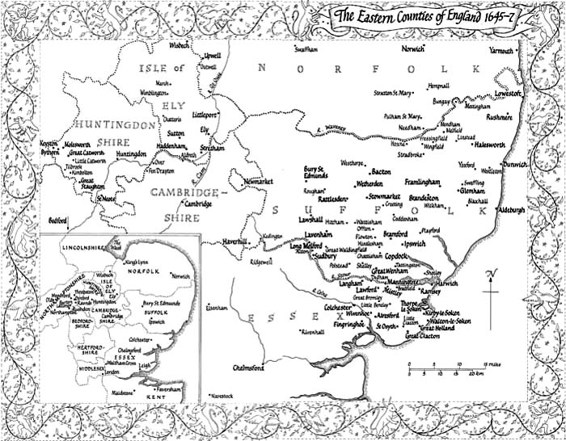

In this world, one of the strangest and most pervasive beliefs was that in witchcraft: unseen power, thought by many to be diabolical, harnessed for good and evil ends. Since this idea surely predates written records, and in New Age religion endures today, its historical significance mainly depends on the fact that between 1563 and 1736 witchcraft was a statutory offence punishable by death. Cases varied in character and cause; prosecution levels fluctuated over time and affected different regions in different ways. But England experienced only one witch-hunt worthy of the name a sustained persecution over a wide area, orchestrated by people calling themselves witchfinders. It happened in the counties of East Anglia during the civil war of the mid 1640s.

At the centre of this tragedy stand a pair of minor gentlemen, Matthew Hopkins and John Stearne. How many suspects they interrogated is unknown; there were perhaps three hundred, of whom a third were hanged. Although much of Hopkins life and the witch-hunt he inspired remain obscure, his notoriety has generated many myths. The orthodox version is a fable of wickedness, madness and perversion that banishes ambiguity and passes over unsightly gaps in the record. Yet however distorted this image, the fact remains that two men really did scour eastern England for witches a story that deserves to be told without recourse to fantasy or fiction. Our seventeenth-century ancestors were mostly decent and intelligent people who could sink to the worst cruelty and credulity at times of intense anxiety. This is a book that reaches beyond monstrous stereotypes to a constituency of unremarkable people, who, through their eager cooperation with Hopkins and Stearne, themselves became witchfinders. In this they resemble the provincial nobodies of the twentieth century who engaged in genocide, demonstrating to the world the banality of evil.

Hopkins the witchfinder immortalized. He may have been responsible for the hanging of sixty witches in one year, as this eighteenth-century caption suggests, but it was not in the reign of fames I, nor is there any evidence that he himself was hanged as a wizard

This story had been in my mind for years, but it took film-maker Jonathan Hacker to make me see a book in it. I am grateful to him and to many besides. My agent Felicity Bryan has supported me throughout, and at John Murray Roland Philipps and Rowan Yapp have been enthusiastic and efficient. My diligent copy editor Liz Robinson made many valuable improvements to the text, as did Adam Lively, Ros Roughton and Sheena Peirse. Sheena arranged a stay in the haunted Witchfinder Suite at the Thorn Hotel in Mistley an unforgettable experience. Patrick Goodbody kindly invited me to his house at Great Wenham, once home to the Hopkins family. Acknowledgement is also due to the staff of the Public Record Office, House of Lords Record Office, British Library, Cambridge University Library, Bodleian Library, Dr Williamss Library, Thomas Plumes Library, the Pepysian Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, and the county record offices at Bedford, Bury St Edmunds, Cambridge, Chelmsford, Colchester, Hertford, Huntingdon, Ipswich, Kings Lynn, Northampton and Norwich. Harwich Town Council also generously granted me access to their archives.

Historians who have shared their time and research include Frank Bremer, Peter Elmer, Carolyn Fox, Ronald Hutton, Mark Lawrence, Diarmaid MacCulloch, John Morrill, Keith Parry, Jim Sharpe, Alex Shepard and Heide Towers. I am most indebted to Robin Briggs, Ivan Bunn and John Walter for commenting on an early draft. I would also like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Board for funding sabbatical leave, likewise the Master and Fellows of Churchill College, Cambridge for their indulgence.

If Robert Louis Stevenson was right, and man really is but a devil weakly fettered, I can only say that the generous beliefs and impositions of all those mentioned here have mattered more.

Authors Note

Seventeenth-century England had yet to convert from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. This meant that the New Year began on 25 March. To avoid confusion, I have rendered all Old Style dates as New Style, with the year starting on 1 January.

Original spelling has been kept for quotations, although punctuation has been modified to improve the sense of certain passages. As even within the same document the spelling of names tended to be erratic, these have been standardized for the sake of consistency.

Prologue

T HE CHRISTMAS OF 1644 was a joyless time in the Essex town of Manningtree. Easterly gales funnelled down the Stour estuary, the river froze an iron grey, and snow drifted high against the warehouses. In the lanes leading up from the harbour the poor fretted over dwindling stocks of food and fuel, and at the waning of each pale sun huddled round fires, relishing their pottage and bread. At least in previous winters there had been festive cheer and revels. But now, throughout England, not only had the puritan authorities denounced celebrations as superstitious, but Christmas Day coincided with a compulsory public fast. Unthanked in church for the Saviours birth, God heard only the usual prayers that the old and frail, the young and the sick, and soldiers still fighting the war between king and Parliament, should be spared their lives until the blessed release of spring.