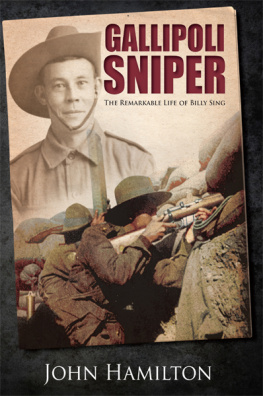

GALLIPOLI SNIPER

The Remarkable Life of Billy Sing

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright John Hamilton, 2008

The right of John Hamilton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-901-1

eISBN 9781473847613

First published as Gallipoli Sniper: The Life of Billy Sing

by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd., 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please email: info@frontline-books.com,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Those heroes that shed their blood

and lost their lives

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

here in this country of ours

You, the mothers,

who sent their sons from far away countries

wipe away your tears;

your sons are now lying in our bosom

and are in peace.

After having lost their lives on this land they have

become our sons as well.

Mustafa Kemal Atatrks 1934 tribute to the Anzacs at Gallipoli ,

now inscribed in Turkish and English on the memorial at

Ari Burnu on Anzac Cove

Despatch from Gallipoli

Ryries Post

Gallipoli

8 September 1915

There is a champion sniper in the 5th Regiment called Sing. He is a half-bred Chinaman and has shot 119 Turks since we have been here. He spends all day and every day in a sniping position with a telescope and rifle and if they show their heads at all, he has them. He says the silly fellows will put their heads up.

Brigadier-General Granville Bull Ryrie, Commanding Officer,

2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade, letter home to his wife,

My Darling Mick

Contents

Snipers Moon

I t is stand-to time here on Gallipoli. Three-thirty in the morning. An icy wind sweeps down from the north from somewhere far beyond Turkey, far beyond the Black Sea. The pilgrims huddle in their sleeping bags, blankets and doonas for warmth, stamp their feet, thump their arms, clap their gloved hands, pull their beanies down over brows and ears. It is always cold here, just before dawn. It always has been so; Gallipoli is a timeless place of cold dawns and harsh days and blue-black nights.

Nature is already stirring. In the thorny thickets up in the gullies and along the sharp ridges, tiny birds are beginning to flit and twitter. Man, the hunter, if he had to lie still here for hours at a time; man, if he were a sniper nearly 100 years ago, would have time to identify them. The bobbing of the Black-headed Bunting, the flash of the Red-rumped Swallow, the cooing of the Turtle Dove, the purposeful darting flutter of the Bee-eater, out hunting too, in pursuit of the heavy black hornets that drone up the valleys and build their nests in the cliff holes here on Gallipoli. The Turks have a special name for these hornets. They are called the eekarilari, and when the eekarilari are out feeding among the spring wildflowers that sprinkle the hills they are to be avoided. These hornets operate like an army and even post sentries among the purple blossoms of the Judas trees in the war cemeteries to noisily sound the alarm and angrily repel invaders from their country.

Through his folding brass telescope, man the hunter, with time on his hands, could probably see across to the big salt lake in the north, and if the morning dawned clear and the firing was not too heavy he might see hundreds of White Storks wading and feeding near the edges.

Yesterday and today, nature crosses time on Gallipoli. Todays pilgrims have crossed the straits of the Dardanelles, from anakkale on the Asian shore to Eceabat on the peninsula, to be here for the dawn.

As the ferries cross the Dardanelles they head towards a landmark, a huge white sign carved into the eastern slopes of the Kilitbahir Plateau on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Below a ridge etched with pine trees a Turkish soldier stands, rifle in one hand, the other arm flung imploringly, defiantly, upwards towards the words:

Dur Yolcu!

Bilmeden gelip bastiin,

Bu toprak, bir devrin battii yerdir

The opening words of the patriotic poem are by a national figure, Necmettin Halil Onan. In full, they translate as:

Stop passer-by!

The ground you tread on, unawares,

Once witnessed the end of a generation.

Listen, in this quiet earth

Beats the heart of a nation.

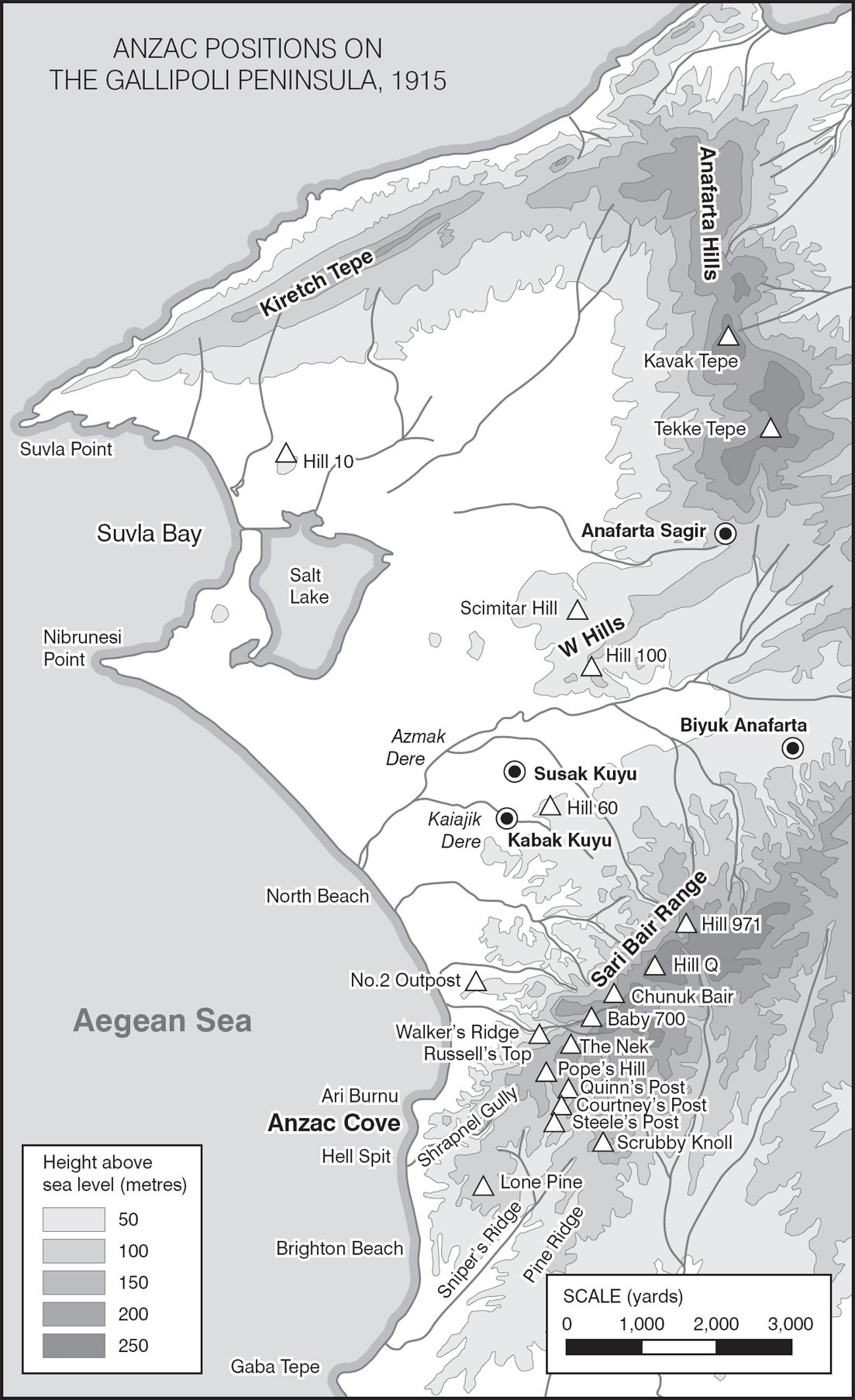

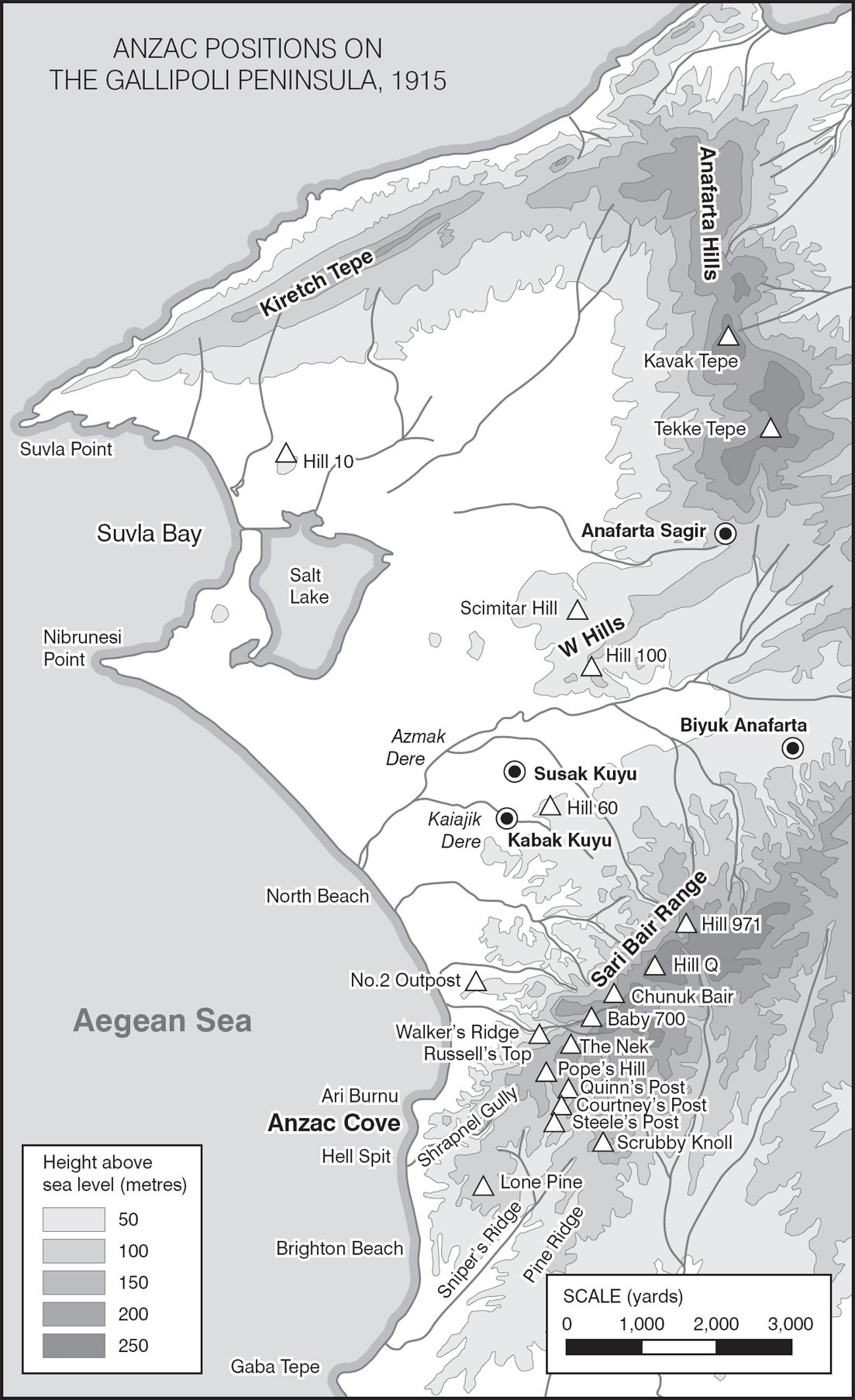

Todays pilgrims are waiting in the cold for the soft dawn on Anzac Day, here at the commemoration site at North Beach, just around the corner from Ari Burnu, the small northern point which marks the beginning of Anzac Cove. They have come both to remember and to try to understand.

Ari Burnu means the place of the bees, and on a warm spring day here the big black eekarilari drone their sentry patrol over a small cemetery, which has purple lilacs growing among the flat grave markers.

By the evening of 25 April 1915, some 16,000 troops had landed on this shingly, stony beach, only about 600 metres long and 20 metres wide, on a remote peninsula at the very end of the world. They charged upwards through chest-high scrub and thorny bushes into the ragged, rugged yellow gullies beyond. They found a strange and foreign place, so very far from Australia and home, a place now immortalised as part of Australias own solemn day of remembrance a day commemorating a victory of the spirit, a celebration of something we proudly call mateship, forged out of the reality of a bloody defeat. For there were already over 2,000 young men killed and wounded by the very first night of the landing; bodies crowded onto coarse sand and shingle and flat grey stones the nightmare beginning of a campaign that lasted for eight-and-a-half months.

Altogether, 60,000 Australians came here to fight against the Turks, who were defending their homeland, the soldiers hunting each other through the yellow flowering gorse and the delicate wildflowers of the hills and gullies.

It is country made for snipers. The Anzac and Turkish positions often overlooked each other. Each side sent out marksmen to hunt and stalk and snipe, to wait and shoot and kill, creeping with stealth through the green and brown shrubbery, along with the darting birds at home in the bush in a coastal area no bigger than a small hobby farm.

The size of the Gallipoli battlefields overall is tiny, easily covered by car in a day. But their quietness comes hand-in-hand with the brooding enormity of death, the realisation of the scale of human wastage that casts its long shadow over such a beautiful landscape.