OTHER BOOKS BY CAROL POLSGROVE

Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause

Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement

I t W as n t P r ett y , F olks, B ut Did n t W e Have Fun? Esquire in the Sixties

When W e W e r e Y oung in Africa: 1948-1960

by Carol Claxon Polsgrove

Culicidae Press

Culicidae Press, LL C 5th Street

Ames, IA 50010 USA

www.culicidaepress.com

WHEN WE WERE YOUNG IN AFRICA: 1948-1960. Copyright 2015 by Carol

Claxon P olsgrov e. All rights reserved.

For the authors website, go to www.carolpolsgrove.com

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanized means (including photocopying, recording, or information stor age and retrieval) without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For more information, please visit www.culicidaepress.com

Cover design and interior layout 2015 by polytekton.com Author photo by Carol Stangler

For Cora

Imagine

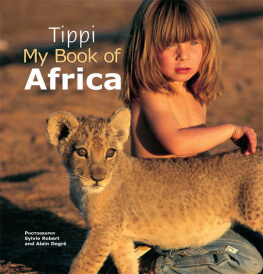

Imagine you are watching a movie and suddenly the action stops and the credits begin to roll. Leaving Africa was like that. I had been going along in my African story, full of its sights and sounds and smellschildren balancing kerosene tins on their heads, drums rumbling at night, air scented by smoke from charcoal and wood fir es. . . And then: Cut. It was over.

After twelve years of growing up mostly in West Africa, I was back in the United States, where people thought growing up in Africa was strange and growing up the daughter of missionaries was even stranger. I learned to avoid mentioning that part of my life at all, because if I did, I would feel the stereotypes close round me. I did my best to pass as American without ever quite succeeding. When my mother asked me in her last days, Do you appreciate your African childhood? I replied with cruel honesty, Yes, but now I dont belong in America.

Just weeks after her death at the age of ninety-six, I sat myself down in a state of survivors freedom to explore the childhood I had tried to put behind me. I poured out memories across a yellow notepad and began reading the letters Mother had passed on to meintimate letters she and Daddy had written back to family in Kentucky, letters I myself had written from my boarding school in Nigeria. As a historian I already understood the richness of life told in letters: the way secrets spring from their pages. Thus innocently (if any historian can be said to be innocent) I beganand found myself tangled up in a story I had not just forgotten but had never known.

That Is What the Matter Is

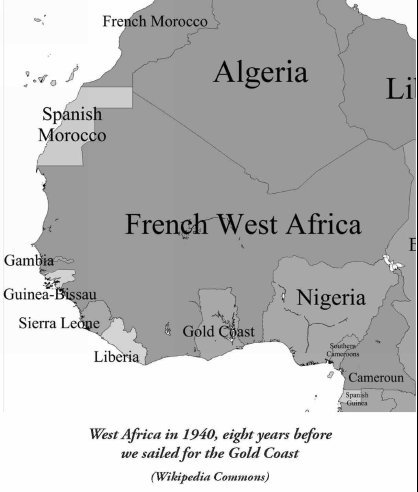

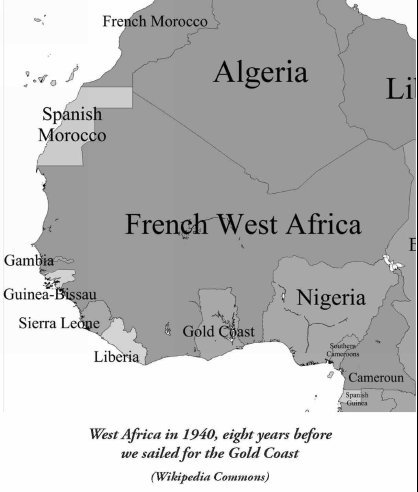

Hardly any travellers now realize what I learned at the age of three: how vast is the expanse of water that separates the worlds continents. My daughter and her friends have flown from one continent to another. None has yet taken a ship from the United States to Europe, much less from the United States to Africadays on the blue sea with its distant horizon and the ship itself nearly always alone.

I can scare myself now just thinking about that little ship by itself on the great Atlantic and little me on that little ship, though at the time, to judge from the letters Mother and Daddy wrote home, I did not seem worried at all. I was the only child on board; everyone watched over me. Mother made a harness for me so I would not fall overboard. The first mate hung up a swing for me. The chief engineer gave me a doll. The chief steward gave me cookies and fruit. The nurse gave me candy. Daddy made a hypodermic needle out of modeling clay and Iremembering all the shots wed had before we started outgave him a shot.

While Mother suffered seasickness for the first few days on board and Daddy thought about storms that would send us to our deaths were it not for God watching over us, the only thing that bothered me was the loud blast of the foghorn at a distant ship our first night. I remember the foghorn, and I remember the little dog on the ship that jumped into the sea and how the first mate stopped the ship so we could all look for the dog in the great sea of choppy water and how someone saw him and a sailor jumped in and brought him back to the ship and put him into a bucket lowered down from the deck and climbed up a rope ladder himself to safety.

And I remember the very day I came to shore in the Gold Coast.

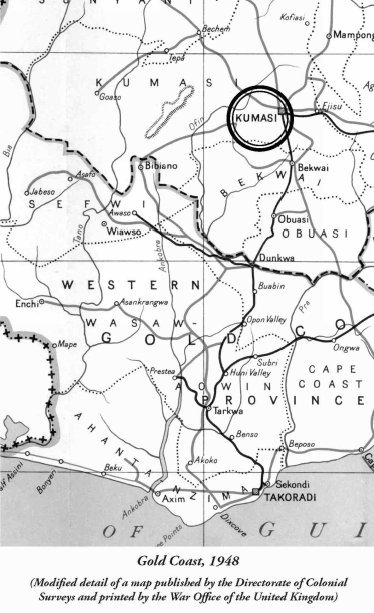

The ship had docked outside the po r t of T akoradi, where there was no room for us yet in the harbor. My parents went ashore on a launch to go through customs, leaving me behind with a fellow passenger for what they thought would be a few hours. When the captain discovered they were gone, he was furious. It would be the next day or longer before the ship could get into port and the sea had turned too rough for Mother and Daddy to get back to the ship.

And so he himself carried me down a swaying gangplank and with a great leap landed us both in a little boat rising and falling with each swell of the wave. I remember the leap, the little boat rising up and down on the dark water below us, how the captain jumped and nearly fellbut how safe I was in his arms.

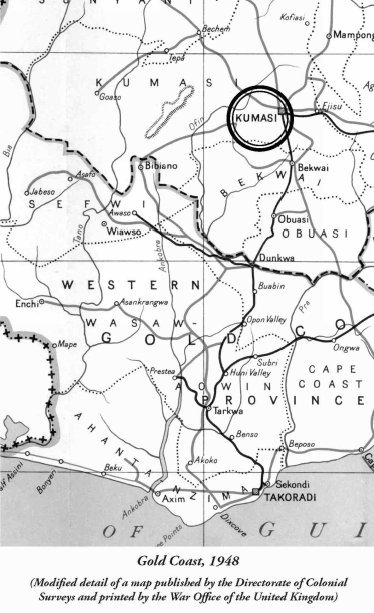

F r om T akoradi, the G old Coast po r t whe r e w e landed on June 9, 1948, we rode a train through a deep forest, accompanied by the Yoruba pastor of the Baptist church in Kumasi, our destination. In the three years of my life in segregated Kentucky, I had possibly never met a black person, though surely I had seen black people in Louisville, where wed lived at the Southern Baptist seminary. Now, everyone around us was black, even our fellow Baptists who met us at the train station in Kumasi, and I wanted to know why, and when Mother said God made them that way, I wanted to know why he made so many.

We saw no other white person the next day when we walked to church among the crowdsbarbers plying their trade, women wearing colorful headties and babies on their backs. At the Baptist Church, started by Yorubas from Nigeria, we were the only white people there, too, except for the albino man who walked around with a stick taking whacks at noisy children. I remember him well, how he looked like me, but nothis fuzzy hair murky yellow. He frightened me, and so did the big mean-looking vultures perched on the walls around the courtyard where we sat, their long necks raw pink, their bulging eyes peering down at the crowd looking for prey, ready to pounce, especially on the one small blonde girl wearing glassesme.

We went to church twice that day, once in the morning and again in the afternoon. Daddy prayed for the dedication of two babies and in the afternoon service, preached. An interpreter from Nigeria translated his English words into Yoruba, sentence by sentence. This has been a great day, Daddy wrote home. It was not as hard as a day at Long Lick, a country church he had pastored in Kentucky, and it was not uncomfortably hot. Already picking up the patois, he pronounced our new town a good city plenty native good. When Mother visited the homes of the local Baptist school teachers and the pastor in the afternoon, though, she confessed she was shocked at what she called the nativeness of itthe open fir e outside where everyone did their cooking, the plain rooms with one table, no chairs.

Next page