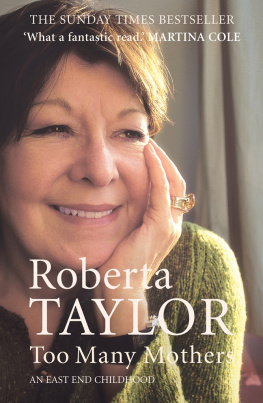

Too Many Mothers

Roberta Taylor is one of Britains most respected actresses. A member of the Glasgow Citizens Company, Roberta has worked for years in theatre. In 1997 she became a household name when she played Irene Raymond in the BBC soap EastEnders. She now stars in ITVs The Bill. She lives in London.

A marvellous book! I couldnt put it down. Roberta Taylor brings that era and that part of London zinging to life with such an authentic voice. Its so rare to find East Enders given their real voice. Helen Mirren

A gut-wrenching memoir that still has you gasping with laughter. I dont know of any other book that captures the stink of poverty like this and still celebrates. A hell of a book. Give it to your prosperous friends who wonder what its all about. Frank McCourt

The Taylor familys mid-20th century version of East End life is discomfortingly close to Dickenss depictions of survival in the slums a century earlier. All the same there is a tremendous generosity and a good deal of dark humour in Taylors telling of her familys story Reading Taylors prose is like listening to a fascinating and feisty friend. Melanie McGrath, Evening Standard

As mordantly funny as it is affecting. Paul Bailey, Independent

Engrossing Michael Moorcock, Guardian

Compelling Mark Sanderson, Sunday Telegraph

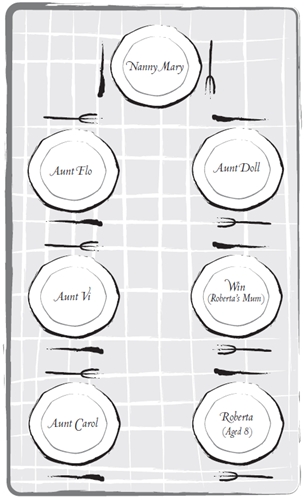

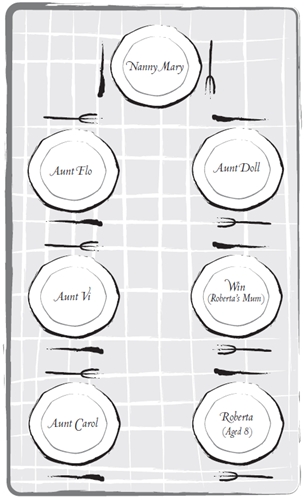

The actress familiar to fans of EastEnders and The Bill with a gob-smacking memoir of her early life and the extended family who brought her up. This included the wily matriarch Nanny Mary and a host of aunts: Doll, Flo, Violet and Carol. Like the most far-fetched of soap operas, except you couldnt make this up. It would be a brilliant Radio 4 Book of the Week. The Bookseller

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Atlantic Books.

This ebook edition published by Atlantic Books in 2012.

Copyright Roberta Taylor 2005.

The moral right of Roberta Taylor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Some of the names in this book have been changed.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781848872561

Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26/27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

For Elliot, Jo and Ellis

The Boxing Day Table

Boxing Day 1956

M ary eased her heavy legs out of bed and sat up. The room was like an icebox. Her feet fumbled around in the dark and found the torch. It was five oclock in the morning and she had a hectic day ahead of her. The corpse that had been lying next to her gave off a fart which blew Bob into a more comfortable position. His gaping, gummy mouth closed with a damp smack. She shone the torch over the bed and grabbed one of the overcoats that masqueraded as blankets, shivered herself into it, and stared at him in the brutal pencil of light.

His face has eaten him, she thought, and remembered the different face and body she had married all those years ago.

CHAPTER ONE

Mary

M ary Roberts, ne Burke, started smoking when she was nine years old, had her arms tattooed by the age of fifteen, and married my grandfather, Robert Victor Roberts, at eighteen. She shuffled the facts of her life to suit her intentions. She swore that she was born on 8 August 1900 to an Irish tinker family. Her birthday was always celebrated on the eighth of August, even though her birth certificate insists that she poked her nose into the world on 13 May 1900. Like a brass band on a Sunday morning the speed and energy of the cockney accent cooked very nicely thank you with the southern Irish tones and vernacular of her parents. The scenic route of her life would not have much to do with geography; she lived and died in the East End of London.

Mary sauntered away from her family home, away from the slums of Poplar, without so much as a by-your-leave, in February 1918, and walked four grim miles east to Bob Robertss mothers house in West Ham. She was pregnant. How and where Mary met Bob had never cropped up. He came from a better class of cockney, apparently. Perhaps they washed more often, had antimacassars, books, and sat at the table to eat. Marys children were in no doubt that it was the Roberts side that was the civilized side.

Would he marry her? Of course he would. She was gorgeous. Pale skin, green eyes, a mass of complicated red hair, and a cheeky little figure with a temperament to match. A Shetland pony in human form.

They whispered their dilemma in the privacy of Clara Robertss front parlour.

He couldnt marry her right at that moment, he had to return to sea in two days time. She hadnt reckoned on his going away so soon, and neither had he, but there was a war on and the Merchant Navy had an important job to do.

If Bob and his brother William managed to survive, they would be away until Christmas at least.

In this situation, its all hands on deck, he tried to explain to her.

All she owned she stood up in. She didnt look that much different from most poor girls of the time, but for her hair, her swagger, and the minx-eyed look shed give instead of a straight answer. Leaving her, Bob braced himself and walked to the scullery.

His mother and brother took the news better than they might have done in peacetime. Clara had bigger things to fret about now. Her boys were going away and she couldnt guarantee she would ever see them again.

Today was Marys first meeting with Clara and William, and her first meeting with the inside of their house. She had sidled past a couple of times last year, out of curiosity, when she had been waiting to meet Bob at the street corner.

Her own living arrangements had consisted of a bug-infested tenement, surrounded by thieves and vagabonds. The daffy of fourteen Burkes shared one and a half rooms, one cold tap and a black cauldron on the open fire stewing lumpish, watery broth. An iron double bed catered for her mum, dad, and the three youngest toddlers. Two large mattresses on the floor slept the nine other Burkes: girls in one, boys in the other. She had slept with somebody elses feet in her face all her life.

Here, she was in a real house. Mary sniffed her future in the beeswax of the parlour. On the mantelshelf were two postcards with camels on them, a wooden-framed photograph of Bob and William in matching dark overcoats, a pair of pewter candlesticks, and a small metal candle-snuffer. The shelves on the wall to the left of the fireplace were home to a pink flowery tea set, the six cups, face down in their saucers to keep out the dust, separated by the round fat teapot. On the top shelf, taking pride of place, she eyed up an ancient-looking carved ornament of a withered old man.

She ran her fingers over the highly polished sideboard against the opposite wall and looked at the squat wooden clock sitting on a lace runner.

Three oclock in the afternoon.

Thursday, 28 February 1918, she reminded herself.

Stealthily she opened the sideboard drawers. In the left-hand drawer, packed to the gunwales, lived pieces of yellowing lace and neatly folded gentlemens handkerchiefs. The right-hand drawer contained a pile of formal-looking documents, a pair of scissors, some buff envelopes, and half a dozen collar studs. Right at the back of the drawer she spotted something else. A roll of large white five-pound notes gripped by a rubber band.

Next page