Alexander Werth (19011969) was a Russian-born British writer and war journalist. He was the BBCs correspondent in the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1945, and the Guardian s correspondent in Moscow from 1946 to 1949. He was one of the first outsiders to be allowed into Stalingrad after the battle and wrote several books describing his experiences.

Alexander Werth was one of the greatest war correspondents of World War II and his descriptions of Leningrad under siege are as powerful today as when they were first published.

Antony Beevor

Werth was the best outside observer of wartime Russia. Astute, independent-minded, a superb writer and not least a native Russian-speaker, he saw through the propaganda to the heart of the country like no other.

Anna Reid

LENINGRAD 1943

INSIDE A CITY UNDER SIEGE

ALEXANDER WERTH

Introduction by Nicolas Werth

Published in 2015 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2010 Tallandier

Copyright English translation of introduction 2015 I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

The right of Alexander Werth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the Estate in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

ISBN: 9781780768724

eISBN: 9780857735027

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

This book was originally intended to be merely a chapter in a much longer book on the war in Russia but many months may elapse before this longer book is completed and I felt, even before Leningrad was finally liberated in January, that the story of that city should be told by itself.

Leningrad holds a peculiar place in the Russian war. Its story can scarcely be regarded as a cross section of the war as a whole. It had during those 29 months of the blockade and semi-blockade a mass of military, organisational and human problems peculiar to itself. On the other hand, there were numerous aspects of the war in Russia not to be found in Leningrad. It is not without significance that during the blockade, and even after the blockade was partly broken, people in Leningrad should have continued to distinguish between Leningrad and the mainland.

When I was in Leningrad in September 1943, many people foretold that Leningrad would be liberated by a drive of the Red Army to the Baltic from Nevel or Vitebsk. They said so with a touch of regret and apology. One understood their feelings. And today one feels that there is a great poetic justice in the fact that Leningrad should have been liberated not from outside but by its own troops, the troops of the Leningrad front.

Leningrad has a large share in Russias glory, but it has also a human greatness peculiarly its own. In Leningrad soldiers and civilians and by civilians I mean men, women and children were more completely united in their struggle and their fate than anywhere else, with the possible exception of Sebastopol.

Two things encouraged me to write this book. I am the only British correspondent to have been in Leningrad during the blockade, and the greater part of this book is a record of all I saw and heard in Leningrad during my visit last autumn. That visit will remain to me one of my three or four most memorable wartime experiences. A few pages are added on my more recent visit in February 1944. Secondly, Leningrad (though it was then called St. Petersburg) is my native city. I lived there till the age of sixteen those early days are described in the preface to my book Moscow 41 but even now, after an absence of more than 25 years, I knew every street corner, and the stones of Leningrad had more meaning to me than those of any other town except perhaps London and Paris.

In this book I have recorded in detail what I saw and heard, but refrained from drawing too many conclusions. Let the details in their cumulative effect speak for themselves.

In conclusion I would like to record my gratitude to Mr. Molotov for having authorised my September visit to Leningrad, to Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, H.M. Ambassador in Moscow, for his encouragement and help, to the Press Department of the Foreign Affairs Commissariat for having arranged the visit, to my friend Dangulov and Lieutenant-Colonel Studyonov for their hard work and their good company during those days, and finally to all the people in Leningrad who in difficult conditions gave me so generously their time and their hospitality. The names of most of them will be found in the narrative that follows.

Outside Russia I wish to thank the Editor of the Sunday Times for kind permission to reproduce here some of the material previously published in that journal, and my warmest thanks go to my friend Leonard Russell for having agreed in my absence to see the book through the press.

A. W.

Moscow, February 1944

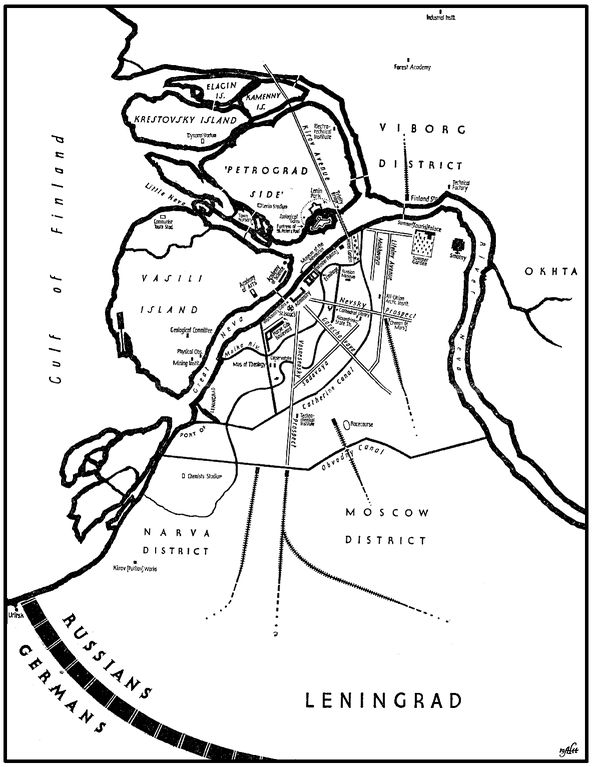

Map of Leningrad and surrounding region, 1943

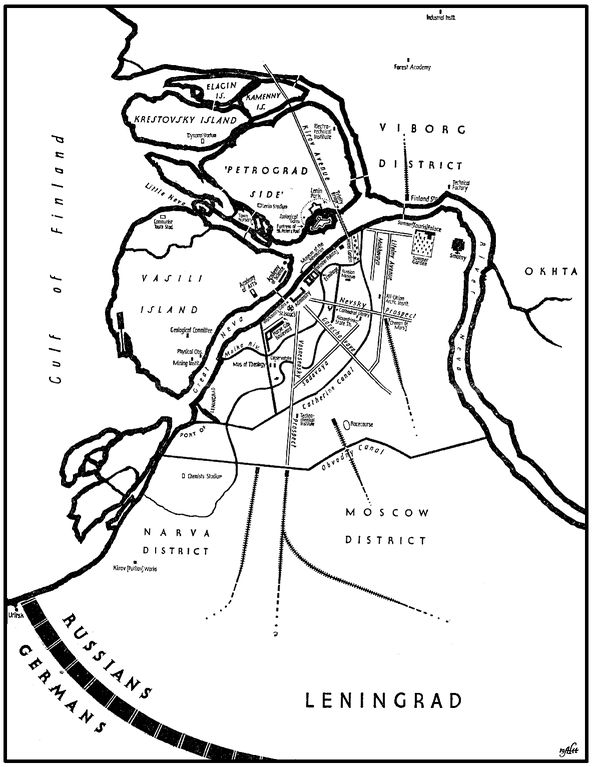

Map of Leningrad, 1943

Introduction

by Nicolas Werth

On 24 November 1942, His Britannic Majestys Ambassador, Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, put the following request to Vyacheslav Molotov, the Peoples Commissar for Foreign Affairs: authorise the British war correspondent Alexander Werth to come to Leningrad to compose a piece on the city and its heroic defenders, which would be of global significance. A few days later, Molotov replied in the negative: At present, we cannot authorise Alexander Werth to visit Leningrad. We are trying to keep the sufferings endured by the inhabitants of Leningrad from becoming too widely known. Until now, these sufferings have only been portrayed in a very biased fashion in the press and in newsreels.

Alexander Werth was thus obliged to wait almost a year before, in September 1943, he finally received authorisation to come to Leningrad. Beginning in January 1943, a successful Red Army counter-offensive had finally broken the stranglehold the Wehrmacht had had on the city since September 1941. Nevertheless, when Werth arrived in Leningrad the German lines were still only 3 kilometres from the Kirov factories in the suburbs south of the city. The devastating aerial bombardments had ceased, but Leningrad remained a city on the front line, regularly pounded by the German artillery. The worst was over, however, for starvation was by and large no longer killing the inhabitants of the besieged city. Werth was the first foreign correspondent (and the first Westerner) to record what remains one of the great urban tragedies of World War II: the longest siege ever endured by a modern city, during which nearly 700,000 civilians starved to death.