The right of Wendy Appleton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

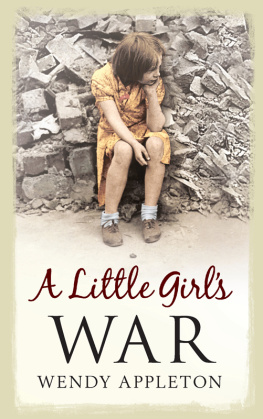

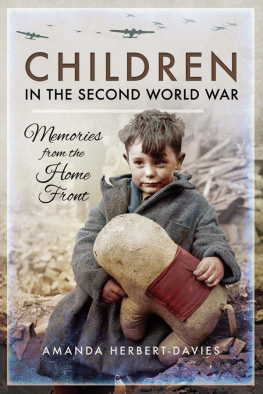

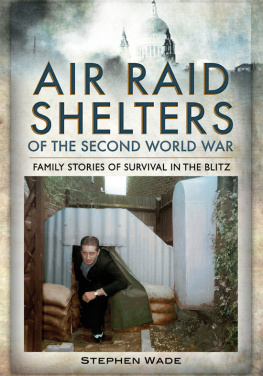

Brian and Wendy outside the shelter in the early years of the war.

I can remember as if it were yesterday. That spring day back in 1944. In a small infant school in Kent, the Garden of England they called it, where, in orchard upon orchard, apples, pears, plums and cherries grew in abundance. (We would drape the twin ruby-coloured cherries over our ears as earrings.)

The sheep grazed peacefully among the awakened fruit trees, now clothed in blossom, happy to feel at last the warming rays of the sun after the chill of a long grey winter. Soft, creamy newborn lambs, long tails shaking with delight, guzzled their mothers milk, or chased and gambolled together, then suddenly leaping into the air with the sheer joy of being alive. Pink and white blossoms blown by the wind sent petals falling and drifting like confetti to the fresh, damp emerald grass beneath. Blackbirds perched in the branches of the fruit trees singing, their shining black feathered breasts puffed out towards the clear blue sky above, hoping to attract their dull brown mate sitting in the next tree.

Huge grey-white cumulous clouds gathered, bringing the promise of another short sharp shower to wet the grass yet again, and to bring fresh life to the once winter-dormant trees and flowers.

The bees buzzing amongst the apple blossoms paused to gather nectar from each small clump of pale yellow primroses, growing around the trunks of the trees, looking just like blobs of cream among the fresh, quilted leaves. The whole countryside, now full of life, was shaking off the dull days of winter. Ah, spring is here at last!

In the kindergarten class, my teacher Miss Fisher, who wore glasses and had her hair in a tight bun, looking every inch the typical teacher, was just getting into her stride with the simple addition maths lesson. There were posters on the walls of our classroom with numbers one to ten beside domino dots in the same amount. We found it very helpful to count on our fingers. Four neat rows of six small tables and chairs faced the front of the class and the blackboard.

We did our sums, writing them in our exercise books, and then we formed a line, one behind the other, to get our work marked by our teacher, who sat at her desk trying to drum into our heads the theory, and just where we had gone wrong. I stood behind a blonde tousle-headed boy, Roger Edgington; he was wearing a Fair Isle sleeveless pullover and was making rude noises, blowing raspberries and making us laugh, so much so that one little girl wet her pants and made a puddle on the floor. Just as we were about to tell our teacher, the loud wailing of the air-raid siren warned us of an imminent bombing attack. (Jenny Markham was going to have to stay in her wet pants.)

Miss Fisher grabbed her brown leather bag and boxed gas mask from her desk as we all began to hurry for the door, following the drill for the imminent air raid, at the same time grabbing our gas masks off their hooks by the door.

Quick, all of you, one at a time now, down to the shelter; no, not you Wendy, she added, as I passed her. You might as well just run home, you havent got far to go and it will soon be home time anyway.

My teacher was tired, after yet another sleepless night, with an almost non-stop bombardment of enemy bombs the night before. If she had stopped to think, she would have realised that it was not a good idea to send a five-year-old child home during an air raid, but her thoughts were on other things as she shepherded the rest of her pupils towards the door.

The other children, as they had been taught to do, carrying their gas masks, ran quickly across the small playground, to the wide stone steps on the field, near the entrance gate to the school. The steps led down to the underground shelter. Then, pushing and stumbling down the concrete steps, the children found themselves inside the cold, stark grey walls of the air-raid shelter, where the bare light bulbs hung dimly, casting weird shadows on the concrete block walls. With anxious faces, they sat down on the row of wooden benches lining the walls. Quickly, the rest of the school children joined them. The dirty walls were hung with cobwebs and the whole place smelt of pee. But they were used to it and so it went unnoticed. A blackboard and easel, complete with chalk, stood at one end ready for their underground lessons.

I grabbed my coat and gas mask, happy not to have to go down to that smelly shelter again where we seemed to spend hours singing:

Ten green bottles hanging on the wall,

Ten green bottles hanging on the wall,

And if one green bottle should accidentally fall,

Thered be nine green bottles hanging on the wall.

On and on we would sing the song until, at the end when,

Thered be nothing but the sme-ell, a-hanging on the wall!

We sang at the tops of our young voices, trying to drown the noise of the guns and bombs outside, and to keep our spirits up. For us it was all we had ever known. From the year after we were born. Since 1939, England and many other countries had been at war with Germany.

But for now, I ran across the playground and, turning the corner of the one-storey school building, I scampered down the narrow shrub-lined alley beside the school that led to Pelham Road, the road where I lived. Long rows of terraced houses stretched on either side of the road before me. Side by side in groups of four, the small three-bedroom homes looked all alike with their square pocket-handkerchief front gardens, bay windows and small tiled porch roofs above the front door.

The wailing of the undulating warning siren frightened me. I had learned to be scared of that sound and all that it meant. Ominous grey clouds gathered overhead and it started to rain. I paused and looked up. High in the sky above me, I could see three tiny planes, two British Spitfires and a German Messerschmitt, battling it out, their guns blazing.