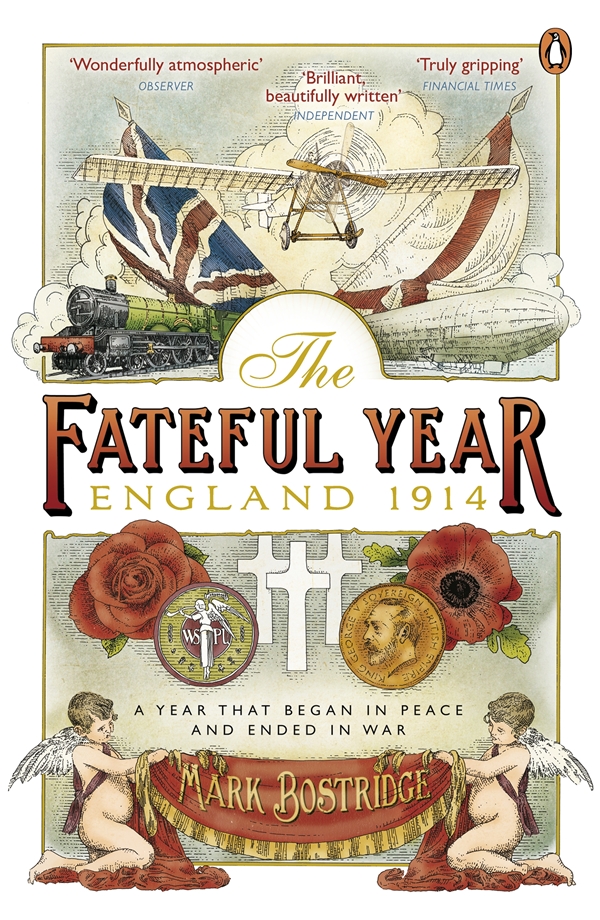

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2014

Copyright Mark Bostridge, 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration: Jonathan Chadwick

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-141-96223-8

Contents

By the same author

Vera Brittain

Letters from a Lost Generation

Lives for Sale

Florence Nightingale

Because You Died

For My Mother

and in Memory of My Mothers Mother

N. W. C. (18891989)

We are like a steamship running at full speed,

through a fog, towards an unknown shore.

Leslie Stephen, War (1878)

So true it is according to my favourite axiom

that the Expected does not Happen.

H. H. Asquith to Venetia Stanley, 25 March 1914

Hows the weather, Jeeves?

Exceptionally clement, sir.

Anything in the papers?

Some slight friction threatening in the

Balkans, sir. Otherwise, nothing.

P. G. Wodehouse, Jeeves in the Springtime (1921)

List of Illustrations

Text Images

(George and Margaret Chapman)

(Imperial War Museum)

Plates

- (Donald McGill Archive and Museum, Ryde)

- (Trustees of the Tate Gallery)

- (Getty Images)

- (Getty Images)

- (Museum of London)

- (Getty Images)

- (Imperial War Museum)

- (Imperial War Museum)

- (Imperial War Museum)

- (Imperial War Museum)

- (Bodleian Library)

- (Imperial War Museum)

Preface

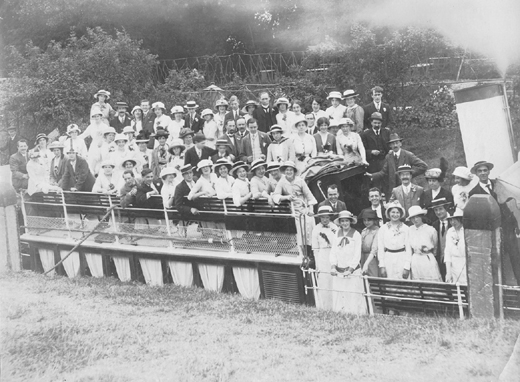

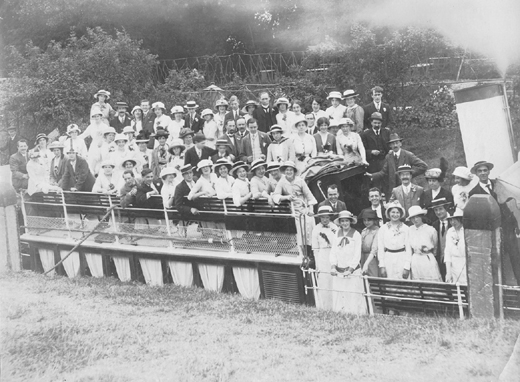

The photograph (overleaf) captures a moment in what was in many ways a typical August Bank Holiday Monday. The staff of the Curzon Laundry, from Acton, the laundry capital of West London, were on their annual outing, a trip on a steam-powered boat up the Thames to Windsor. The weather, as so often in England, had been difficult to forecast. In many parts of the country over the past couple of weeks, there had been a mixture of heavy showers and high winds. But on the afternoon of this river excursion the sun came out and the skies were as blue and cloudless as they ought to have been.

No doubt there were high spirits among the laundry workers, washers, ironers and delivery men, encouraged by the good weather and the consumption of alcohol. The young women wear their prettiest white summer dresses, with miniature floral bouquets pinned to their waists. Many of the young men sport straw-boaters, once the prerogative of gentlemen, but now ubiquitous across the classes. The taking of this photograph whether it was on the outward or return trip isnt known, but one guesses that it was probably on the latter completed their sense of occasion.

Only this was a holiday with a difference. The date was Bank Holiday Monday, 3 August 1914, and it was destined to be a day of final, irrevocable and fateful decision. Even as the camera shutter fell, preserving this carefree scene, the larger issues of peace and war continued to hang in the balance. The imminent threat to Belgium by Germanys army weighed heavily on the nations consciousness. That afternoon, the British Parliament would move decisively closer to entering a European war to defend Belgian neutrality. Nearly thirty-six hours later, Britain would declare war on Germany. Life for many of the men and women on this river excursion would never be the same again, as the country was overwhelmed by a conflict that was to become the first total war in modern history.

Staff from the Curzon Laundry in Acton, West London, enjoying a Bank Holiday outing, 3 August 1914

It seems only natural for us, a hundred years on, to scrutinize the faces in this group for some trace of foreboding, or presentiment about the tornado of change and destruction that was about to hit them. Yet, even if we were able to discern such thoughts or emotions, we would be unlikely to find any sign of them here. War with Germany, frequently imagined and predicted, had none the less managed to creep up on the British people, catching them unawares. It has all come as by the leap of some awful monster out of his lair, the novelist Henry James wrote on the eve of war, he is upon us, he is upon all of us here, before we have had time to turn round.

That shocking transition from peace to war has always been one of the terrible attractions for anyone writing about the English experience of 1914. Philip Larkins popular and much anthologized poem MCMXIV, with its famous lines Never such innocence, / Never before or since, ingeniously dramatizes the way in which the year took an unexpected turn by employing one long sentence without a main verb. Larkins use of multiple present participles evokes the onward flow of time, but the poets voice in the final stanza hints at the violent break that is about to occur, unsuspected by the men and women of 1914. (Larkin used Roman numerals for the title of his 1914, rather than Arabic ones, both in order to suggest the inscription on a war memorial and because he felt that the emotional impact of 1914 was too great for anything I could possibly write myself.)

Larkins poem also mythologizes a vanished English way of life, destroyed by the war, and suggests a world of prelapsarian innocence. In the most obvious sense, of course, England in 1914 was no more or less innocent than any other time or place. Moreover, the first half of the year had seen violent challenges to the established order from three broad areas.

The labour movements acceptance of class-war doctrines had contributed to a wave of strikes, and there were widespread predictions that the country would soon find itself paralysed by continuous outbreaks of industrial action. Secondly, the publicity-seeking stunts of the suffragettes, demanding Votes for Women, had turned increasingly from symbolic gestures of protest to actions which posed serious threats to life as well as property. Finally, the direst portents of all were reserved for the situation in Ireland, where the prospect of a new Home Rule Bill was provoking resistance in Ulster, increasing fears that Ireland would soon be on the brink of a civil war.