PUBLIC

EXECUTIONS

NIGEL CAWTHORNE

This edition published in 2012 by Arcturus Publishing Limited

26/27 Bickels Yard,

151153 Bermondsey Street

London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2006 Arcturus Publishing Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN-13: 978-1-84858-512-6

Picture Credits

Art Archive/Picture Desk, Corbis, Getty Images, Mary Evans, Topham Picturepoint. For more information contact info@arcturuspublishing.com

Contents

Chapter 1

The Roman Way of Death

Chapter 2

Beheading

Chapter 3

Death By The Sword

Chapter 4

The Road to Tyburn

Chapter 5

Hanging, Drawing, and Quartering

Chapter 6

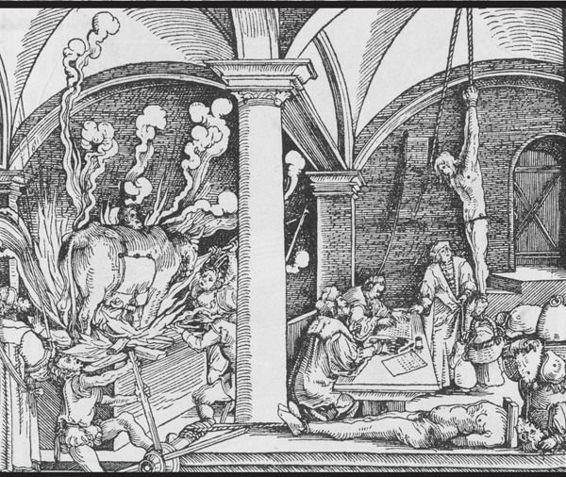

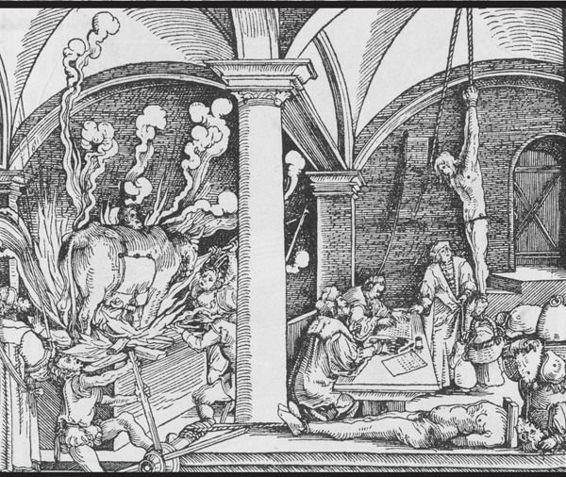

Burning

Chapter 7

The Reign of Terror

Chapter 8

Exotic Executions

Chapter 9

Military Methods

Chapter 10

Modern Methods

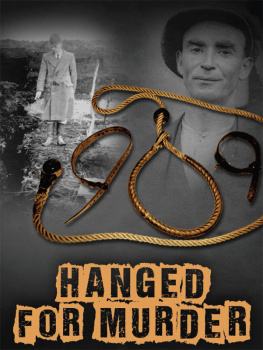

In Britain and the United States, public execution was outlawed in 1868 and in 1936 respectively. However, it is still practised in many countries around the world. These include Iran, Saudi Arabia, China and, some would argue, the United States, where large numbers of witnesses are invited to view the demise of condemned criminals. Most civilized countries, however, view public execution with distaste.

This is, however, a very modern view. In earlier times, an execution behind closed doors was regarded as little more than murder. It robbed the victim of the opportunity to make his final speech from the scaffold and certainly deprived the State of the chance to parade its power before those who fell under its jurisdiction, be they criminals, enemies, or political opponents. Above all, the public missed out on what was considered a great spectacle Christians thrown to the lions in Rome's Colosseum, multiple hangings at Tyburn, guillotined aristocrats at the Place de la Concorde, heretics burned alive at the auto-da-f or the still-pulsating hearts ripped from the chests of war prisoners by Aztec priests at the summit of their temple pyramids.

The theatre of public execution offered further political gains. When Charles I was beheaded, the block was only ten inches high rather than the conventional two feet. This meant he could not kneel for his execution but was forced to lie face down, a position considered by his executioners to be more humiliating.

Beheading was one of the most common methods used in public execution, and it did at least have the virtue from the victim's point of view of being quick. There was also death by beating, boiling, breaking on a wheel, burning, crucifixion, drowning, hanging, keel-hauling, necklacing (officially sanctioned in Haiti), starvation in a cage, stoning, strangulation or a thousand cuts; by being buried alive, devoured by animals, exposed on a gibbet, fried on a gridiron, garrotted, guillotined, hammered to death, hanged, drawn and quartered, impaled on a stake, rent asunder between two trees, roasted alive, sat on the 'Spanish donkey', sawn in half, sealed up in a barrel, sewn inside an animal's stomach, shot at with arrows, stung to death by insects, tied to a mill wheel or a sack filled with animals, tied over the muzzle of a cannon and blown apart, thrown from a height, torn apart between two boats; by having gunpowder ignited through bodily orifices, your heart torn out or your throat slit.

Public executions not only despatched the victims but also brutalized executioners and spectators alike. The Romans, who purposefully pitted inadequate criminals or defenceless Christians against mighty gladiators, saw an advantage in this. They believed public execution taught onlookers to confront death.

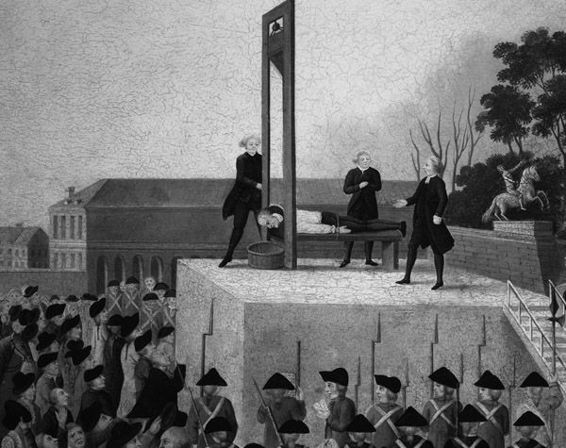

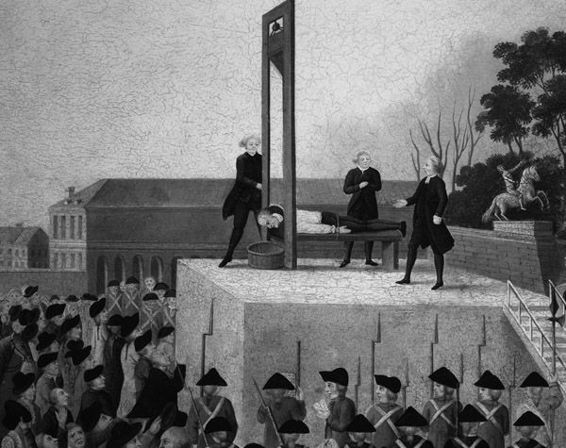

Painting by Alfredo Dagli Orti of the execution of the French king Louis XVI, 1793

No such noble excuse could be made for the huge crowds that gathered along Oxford Road (London's Oxford Street) to see condemned prisoners being taken from Newgate Prison to Tyburn. Popular offenders were showered with flowers and unpopular ones pelted with rotten vegetables or stones. Around the gallows at Tyburn were wooden stands where spectators paid two shillings 10p for a good view. The largest and most desirable stand was Old Mother Proctor's Pews, named after their owner. The whole affair had a carnival feel about it with crowds singing and chanting, and street vendors selling gingerbread, gin, and oranges. There was certainly nothing noble about dying in these places.

CHAPTER 1

The Roman Way of Death

In ancient Rome, death was dictated by social class. At one end, the patricians and the equestrians were allowed to poison themselves in private. At the other, slaves were publicly crucified. Although this form of public execution is now associated with the death of Jesus Christ, it was a common form of capital punishment when the Roman Empire was at its height. Crucifixion was not invented by the Romans there are mentions of it in earlier Greek literature although they seem to have perfected the practice.

Herodotus, the father of ancient history, who lived in the fifth century BC, recorded that the Persian King Darius I ordered the crucifixion of 3,000 Babylonians in about 519 BC.

Crucifixion

When Alexander the Great attacked the Persian Empire in the fourth century BC, he crucified 2,000 men from the Phoenician city of Tyre (modern-day Sur in southern Lebanon) along the beach after the city refused him worship in their temple and forced him into a costly siege. The Romans learned about crucifixion from the Greeks, although they noted that many of the 'barbarian' races (Indians, Assyrians, Scythians, and Celts) also used it. The Carthaginians employed crucifixion until Carthage was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC.

Some Romans regarded crucifixion as uncivilized. In the first century BC, the statesman Cicero called it 'the most cruel and disgusting penalty' and considered it the worst of deaths. The Jewish historian Joseph Ben Matthias (aka Flavius Josephus), who witnessed numerous crucifixions during the Jewish revolt in AD 6670, called it 'the most wretched of deaths'.

The first-century Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca asked: 'Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain dying limb-by-limb, or letting out his life drop-by-drop, rather than expiring once [and] for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree, long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly wounds on shoulders and chest, and drawing the breath of life amid long, drawn-out agony? He would have many excuses for dying even before mounting the cross.'

Next page