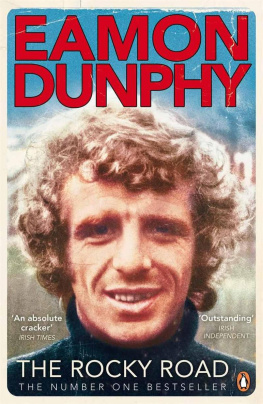

Eamon Dunphy

THE ROCKY ROAD

Contents

By the same author

Only a Game?: The Diary of a Professional Footballer

Unforgettable Fire: The Story of U2

A Strange Kind of Glory: Sir Matt Busby and Manchester United

Keane: The Autobiography ( with Roy Keane )

For my mother, Margaret, my father,

Paddy, and my brother, Kevin

While in the merry month of May from my home I started

Saluted father dear, kissed my darling mother

See the lassies smile, laughing all the while

At my curious style, twould set your heart a-bubblin.

Asked me was I hired, wages I required,

I was almost tired of the Rocky Road to Dublin.

From The Rocky Road, as sung by Luke Kelly

1. Whats in a Name?

On St Patricks Day 1943 amon de Valera addressed the Irish people on Radio ireann. He had been Taoiseach for eleven years. Dev was the most influential Irishman of his time. More than a mere politician, he was the nations spiritual and cultural icon. Often derided by Irish intellectuals in the decades that followed, his vision as expressed in 1943 resonated with a majority of the people he led, among them my mother, Margaret.

Two years after Devs famous speech, my mother would name me after him. If my father, Paddy, had been doing the naming, my given name might well have been Jim, after the charismatic labour leader Jim Larkin. Big Jim was someone my father deeply admired and frequently quoted. The difference between my parents political preferences was irrelevant when set against the deep love they felt for each other. Paddy would sometimes tease Peg, as he called her, about Dev; she might respond by reminding Dad that Larkins finest hour, his leadership of the workers during the 1913 Dublin Lockout, had ended in abject failure when, starved and humiliated, the strikers had shuffled back to work for the cruel merchants who had resisted their claims for a decent living wage.

When my brother was born two years after me, my mother named him Kevin after Kevin Barry, the eighteen-year-old medical student executed by the British in 1920. Barry was offered his freedom in return for the names of his fellow volunteers. He refused to give them and was hanged. Another martyr for old Ireland, as a line from a popular ballad about Barry put it.

My mothers background, like that of so many Irish people, was rural, devoutly Catholic and poor. It was at that constituency that Devs radio speech was aimed:

The ideal Ireland that we would have, the Ireland that we dreamed of, would be the home of a people who valued material wealth only as a basis for right living, of a people who, satisfied with frugal comfort, devoted their leisure to the things of the spirit a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youths and the laughter of happy maidens whose firesides would be forums for the wisdom of serene old age. The home, in short, of a people living the life that God desires that men should live.

Before returning to Devs homily about the virtues of frugal living (there is some guff about patriotic sacrifice to follow), we should note that he was a massive swindler, a con artist who had robbed thousands of Irish and American people of $250,000, which he had raised to set up the Irish Press , a newspaper for the people that he promised would be committed to telling the truth in news.

Founded in 1931, twelve years before the Ireland that we dreamed of speech, the Irish Press was primarily an organ of propaganda for Devs Fianna Fil (the Soldiers of Destiny) party, an organizational mix of the Moonies and the Mafia that was committed to one thing only: the retention of political power.

The well-meaning investors, most of them domiciled in the United States, which at the time was mired in the Great Depression, were gulled by a simple corporate manoeuvre. Instead of receiving shares in Irish Press Limited they received certificates from Irish Press Corporation, which was registered in the tax-haven state of Delaware. Once Dev had the $250,000, Irish Press Limited issued 60,000 A-class share certificates from Irish Press Corporation. Those pieces of paper were worthless. Control of the publishing company would rest with the owner of the 200 B-class shares, the God-fearing patriot amon de Valera. The scam that he dreamed of would not be fully exposed for decades.

Viewed in the context of the share shakedown, the evocative speech of St Patricks Day 1943 acquires an element of cruel, peculiarly Irish farce:

with the tidings that make such an Ireland possible, St Patrick came to our ancestors fifteen hundred years ago promising happiness here no less than happiness hereafter. It was the pursuit of such an Ireland that later made our country worthy to be called the Island of the Saints and Scholars. It was the idea of such an Ireland happy, vigorous, spiritual that fired the imagination of our poets, that made successive generations of patriotic men give their lives to win political and religious liberty and will urge men in our own and future generations to die, if need be, so that these liberties be preserved. One hundred years ago, the Young Irelanders, by holding up the vision of such an Ireland before the people, inspired and moved them spiritually as our people had hardly been moved since the Golden Age of Irish Civilization. Fifty years later, the founders of the Gaelic League similarly inspired the people of their day. So later, did the leaders of the Irish Volunteers. (The IRA!) We of this time, if we have the will and active enthusiasm, have the opportunity to inspire and move our generation in a like manner. We can do so by keeping this thought of a noble future for our country constantly before our eyes, ever seeking in action to bring that future into being and ever remembering that it is for our nation as a whole that future must be sought.

That last reference to our nation as a whole was a sly signal that he had not forgotten the core principle of the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War a united Ireland for which so many of his comrades had given their life. This cause, upon which his leadership and the initial legitimacy of the Fianna Fil Party were founded, had hardly been advanced during his period as Taoiseach.

The reference to religious liberty was similarly disingenuous: his God was Catholic; the Ireland that he dreamed of, ruled by Catholic dogma, was a place that would have been hostile to men like Robert Emmet, Wolfe Tone and Charles Stewart Parnell, all of whom were Protestants offering a truly republican vision profoundly at odds with de Valeras narrow Catholic nationalism.

I have often wondered what drew my mother to Mr de Valera. The answer may be that he wasnt W. T. Cosgrave, Devs main political rival in the 1920s and early 1930s. It is impossible to imagine Cosgrave, a Dubliner, articulating, as Dev did, the romantic vision of Ireland that so appealed to a countrywoman.

In the fiction that is Official Irish history, Cosgrave is a revered figure. He took the pro-Treaty side with Michael Collins and led the first Irish government when the Irish Free State was formed in 1922. Cosgrave was a publican before becoming a gunman, or freedom fighter, as these killers have come to be regarded with the passage of time. My mother wasnt mad about publicans.

But perhaps her affection for Dev, the pious romantic, was essentially a rejection of Cosgraves extreme right-wing politics, which are best summarized in a letter he wrote to a colleague in 1921, when he was minister for local government.

Next page