Table of Contents

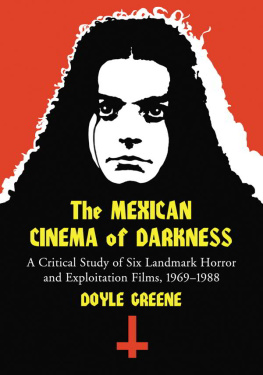

Mexploitation Cinema

A Critical History of Mexican

Vampire, Wrestler, Ape-Man

and Similar Films, 19571977

Doyle Greene

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Greene, Doyle, 1962

Mexploitation cinema : a critical history of Mexican vampire, wrestler, ape-man and similar films, 19571977 / Doyle Greene.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7864-2201-7

1. Exploitation filmsMexicoHistory and criticism.

2. Sensationalism in motion pictures. I. Title

PN1995.9.S284G74 2005 791.43'653dc22 2005011057

British Library cataloguing data are available

2005 Doyle Greene. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Promotional artwork from the 1957 film El Tesoro de Pancho Villa

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Kathleen Newman,

whose enthusiasm for a paper on El Santoin

a course on Mexican cinema at the

University of Iowa made this project possible

Acknowledgments

I owe an enormous debt of thanks to Rob Craig, whose Wonder World of K. Gordon Murray website provided invaluable historical material regarding Murrays illustrious career and Mexican horror cinema. Additionally, Rob contributed numerous insightful comments throughout the course of this project and generously provided several illustrations. Another substantial debt is owed to David Wilt, as my numerous citations to his work indicate. His Films of El Santo website and myriad other sources pertaining to Mexican cinema supplied an indispensable wealth of material, and he also generously provided many illuminating comments and suggestions. Simply put, without the efforts, research, and contributions of Rob Craig and David Wilt, I shudder to speculate to what extent, or even if, my own work on Mexican horror cinema could have developed. Thanks also to Brian Moran at the Santo Street website for his assistance in compiling my own collection of Mexican cinema and Azteca Studios lobby cards.

Thanks to the following academic programs: The Master of Liberal Studies Program and the Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota, and the Film Studies Program and Department of Cinema and Comparative Literature at the University of Iowa. My work in these settings provided both the intellectual inspiration and the opportunity to explore trash cinema in a serious context. Finally, thanks to my family and friends for their support, above all to my late parents, Earl and Laura Greene.

Introduction:

Why Mexploitation?

From approximately 1957 to 1977, one of the more popular genres in Mexican cinema consisted of horror films featuring an array of vampires, Aztec mummies, mad scientists, ape-men, and various other macabre menaces. However, the most striking and famous aspect of these horror films was their incorporation of lucha libre (Mexican professional wrestling), resulting in numerous movies that starred not only fiendish monsters but a variety of popular luchadores (wrestlers), including one of the most important figures in Mexican popular culture: El Santo, el Enmascarado de Plata (The Saint, the Silver-Masked Man)universally known simply as Santo. It is this collection of horror and horror-wrestling movies that have been termed mexploitation by both cult-film fans and, more recently, Latin American film scholars.

Certainly, much of mexploitations notoriety in America has so far centered on its cult-film credentials: the limited budgets born out of the conditions of the Mexican film industry; the surreal qualities generated by their eclectic merging of disparate film genres and other elements of Mexican popular culture; and the enigmatic dubbing of the films provided by exploitation entrepreneur K. Gordon Murray, who single-handedly introduced mexploitation cinema to America via late-night television and drive-ins during the 1960s. Unfortunately, in the United States mexploitation films have been widely ridiculed; at best they are granted a so bad theyre good status.

My own intention in exploring mexploitation cinema is to move beyond the debate of whether, or to what degree, these films have any sort of artistic integrity or legitimacy. Rather, this project will focus on how mexploitation films, as products of a specific time and place, are entertaining, insightful, and, yes, important cultural documents that address the conditions, contradictions, and visions of contemporary Mexican society, politics, and culture. It is my contention that any discussion of the historical and cultural importance of Mexican national cinema could, and should, include the mexploitation era as well as the Golden Age of Mexican cinema or the films of Luis Buuel.

In pursuing this critical history, I have adopted an interdisciplinary approach, combining research in cultural theory, film studies, and Mexican history and popular culture. I pay specific attention to the historical and cultural context in which these films were produced; close textual analysis of specific films; and, perhaps most importantly, the consistent ideological messages these films offer. In keeping with these areas of emphasis, this book is roughly divided into three sections, each focusing on a crucial facet of mexploitation.

The first section, composed of the first three chapters, might be said to spotlight early mexploitation. Chapter One provides an historical overview of Mexicos political situation and the economic conditions of the Mexican film industry in the late 1950s, which laid the foundation for the development of mexploitation; a brief overview of some of the key films and figures in mexploitation cinema; and the subsequent introduction of these films to America. Chapter Two argues that mexploitation can be viewed as far more than camp oddities, but instead forms a strange counter-cinema that addresses key issues in Mexican society: the valorization of mexicanidad (Mexican national identity), the cultural conflict between modernity and tradition, and issues of gender politics. Chapter Three employs what is probably Murrays most famous mexploitation import, The Brainiac, as a specific case study the issues outlined in the previous chapters.

Chapter Four constitutes the second section of this project and is devoted to a historical and critical discussion of the lucha libre films (focusing, perhaps inevitably, on the legendary El Santo). A short history of the lucha libre genre, an analysis of the cultural significance of lucha libre in Mexican society, and an overview of the iconic status of Santo in Mexico provides the contextual framework for a discussion of three seminal Santo films (all of which also address the issues of mexicanidad, modernity, and gender): the Murray import Santo vs. the Vampire Women (retitled Samson vs. the Vampire Women in America), Santo, el Enmascarado de Plata vs. la invasin de los marcianos (Santo, the Silver-Masked Man vs. the Invasion of the Martians), and Santo y Blue Demon contra Drcula y el Hombre Lobo