Table of Contents

Also by Doyle Greene

Mexploitation Cinema: A Critical History of Mexican Vampire, Wrestler, Ape-Man and Similar Films, 19571977 (McFarland, 2005)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Greene, Doyle, 1962

The Mexican cinema of darkness : a critical study of six landmark horror and exploitation films, 19691988 / Doyle Greene.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-2999-8

1. Horror filmsHistory and criticism. 2. Exploitation filmsMexicoHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1995.9.H6G74 2007

791.43'61640972dc22 2007012664

British Library cataloguing data are available

2007 Doyle Greene. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

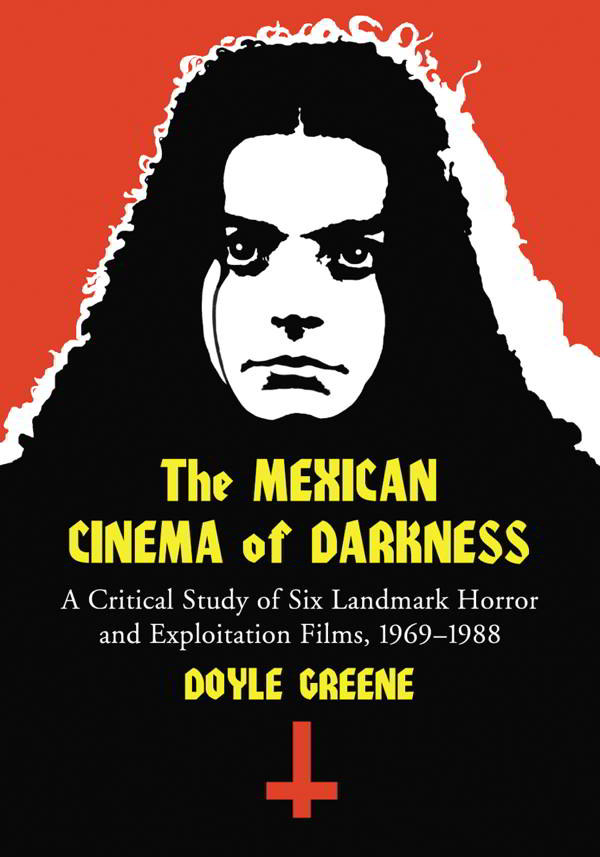

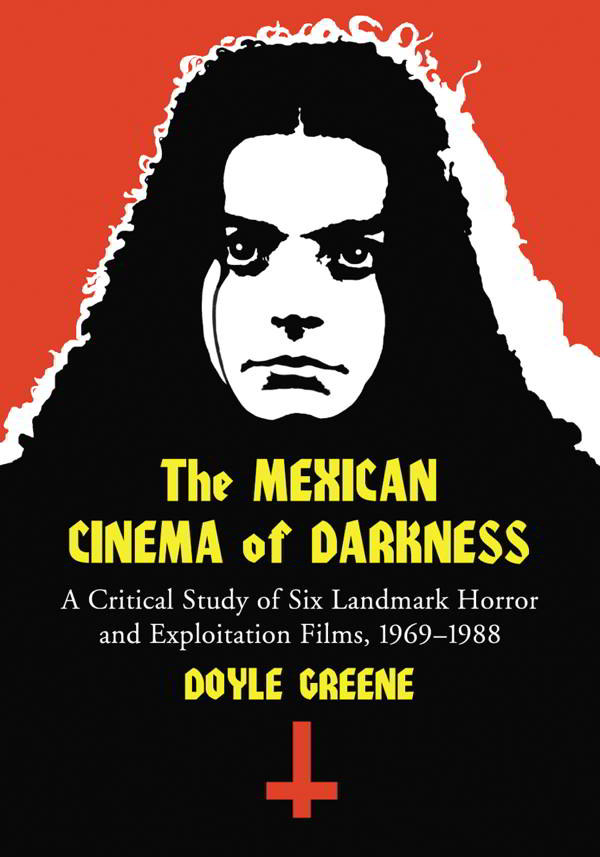

On the cover: Promotional artwork for the 1978 film Alucarda, la hija de las tinieblas

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Richard Leppert:

in gratitude for the many years

of invaluable insight

Acknowledgments

My thanks first to the following people: Rob Craig, for his always welcome correspondence, comments, and his generous gift of the El Topo lobby cards; David Wilt, for his knowledge of Mexican cinema and graciously supplying the illustrated material for the chapters on Juan Lpez Moctezuma.

An immense debt of gratitude is owed to my former instructors and colleagues in the following academic departments: the Liberal Studies Program, and the Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota; the Film Studies Program, the Department of Cinema and Comparative Literature, and the Department of Rhetoric at the University of Iowa. Without the learning experiences in these programs and the possibility to pursue trash cinema in a critical context, this project would not have been possible. A special thanks to Keya Ganguly for her advice and comments on this project, and to Tom Conley for his seminal influence.

Finally, my heartfelt thanks for their continuous support to: John Ray Link and Sophia Green, Mr. and Mrs. Link, Matt Potts, Donn Wingate, and Steve Nacho Fier. A special thanks to Rodney and Jeni Lynch, and especially to Jim Hoyer.

Preface

The Mexican Cinema of Darkness came about through my interest and research on Mexican horror and lucha libre films that eventually resulted in Mexploitation Cinema (2005). This project is a continuation of that work, in that my principal argument remains Mexican trash cinema is more than a collection of camp oddities, but films which addressed social and cultural issues greatly affecting Mexican society: above all, the question of modernity. However, Mexican Cinema of Darkness explores a far different set of films and directors: Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo and Santa sangre), Juan Lpez Moctezuma (Mansion of Madness and Alucarda) and Ren Cardona, Jr. (Guyana, Crime of the Century and Birds of Prey).

While about Mexican cinema, this project was ultimately approached from a perspective of global cinema and politics as well as national cinema and politics. These films were made with international audiences in mind, particularly the film markets in the United States and Europe. In part, this owed to the restraints the Mexican film industry and government placed on content at the time; however, this was also due to the formal ambitions of the films themselves. Jodorowsky and Lpez Moctezuma (perhaps less so Cardona) were consciously informed by international avant-garde cinema and the arts: Expressionism, Surrealism, Postmodernism, and experimental theater ranging from Antonin Artauds Theater of Cruelty to various strains of Theater of the Absurd. Filmmakers such as Luis Buuel, Federico Fellini, and Pier Paolo Pasolini can be seen as key influences along with Eurotrash exploitation filmmakers such as Mario Bava, Jess Franco, and Jean Rollinnot to mention American counterparts such as Roger Corman or Russ Meyer. (This is not to imply Bava, Rollin, or Meyer were necessarily inferior, or even less avant-garde in their own way, in comparison to Buuel, Fellini, or Pasolini). This improbable nexus of the avant-garde and exploitationwhat I have termed avant-exploitationbecame a defining formal characteristic of these films.

The second issue became historical context. These films reflected awareness that the political upheaval occurring in Mexicohorribly manifest in the Tlatelolco Square massacre in Mexico City on October 2, 1968was part of an international wave of political unrest and change: Third World politics in the post-colonial era, the rise and fall of the 1960s counterculture, the political frustration of the 1970s, and the rise of neo-conservatism in the 1980s. My readings consider this context along with the texts themselves. For this reason, this project is interdisciplinary in nature; it draws from film studies, cultural studies, art history, literary theory, world history, philosophy, political science, and especially critical theory ranging from Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Michel Foucault, Herbert Marcuse, and Giles Deleuze and Flix Guattari. Moreover, the interpretations ultimately stem from my own position as a reader engaging these films from a different historical, national, and perhaps even political perspective than the authors of these films.

Admittedly, these readings are not concerned with proving intentionality; ascertaining what a filmmaker intended to say is probably best served by simply consulting a DVD commentary track. In other words, I do not claim that my interpretation of El Topo as an epic allegory of the counterculture is the definitive analysis of an eminently dense and complex film: yet alone the only valid one. Nor do I claim that Birds of Prey was Ren Cardona Jr.s conscious effort to make the low-budget film version of Deleuze and Guattaris A Thousand Plateausbut that a comparative reading can indeed be pursued. My interest in these films, and what I believe is their ultimate importance, are as cultural documents that unabashedly chronicle the chaos, desperation, and uncertainties of the modern world after 1968.

Introduction

Nineteen sixty-eight was a year of worldwide political upheaval. In the United States of America, assassinations and riots seemingly became the preferred methods of political practice. Vietnam became synonymous with the status of international relations. In France, the May 1968 movement of student demonstrations and worker strikes paralyzed and nearly toppled the government of Charles de Gaulle. Keeping the Stalinist program alive, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in August, crushing a popular uprising.

On October 2, 1968, Mexico experienced its own national tragedy. Between 5,000 and 10,000 students in Mexico City staged a demonstration in Tlatelolco Square (the Plaza of Three Cultures). At 6:00 pm, orders were given to open fire on the protestors: a massacre by police, army, and paramilitary forces resulted. Students were bayoneted and shot, some in execution fashion; government forces also raided nearby apartments searching for fleeing students and murdered numerous residents of the neighborhood. Desperate to maintain its public image in world politics, largely due to the 1968 Olympics set to begin in Mexico City on October 12, the Mexican government claimed less than a dozen people were killed; the official figure was eventually adjusted to 32. However, independent news reports and subsequent historical accounts place the number of dead at 325,

Next page