T HE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN the various currencies that appear in Ippolitos account books is enormously complex. Most states in sixteenth-century Europe had their own silver-based coinage. France, which had long been a centralized monarchy, had a single system based on the livre (1 livre = 20 sous = 240 deniers). In Italy, where the peninsula was fragmented into numerous different states, each city had its own local currency: Ferrara, for example, used the lira march-esana (1 lira = 20 soldi = 240 denari), while Rome preferred a decimal system based on the scudo di moneta (1 scudo di moneta = 10 giulii = 100 baiocchi). There were also internationally recognized gold coins, such as the Venetian ducat, the Florentine florin and the gold scudo. The latter appears frequently in Ippolitos account books and could clearly be used across Europe. Wealth was assessed in gold, the currency of inter-national trade, while silver coinage was used for everyday transactions, such as buying food or paying wages. These currencies, gold and silver, fluctuated against each other in response to market forces: during the years 153440, the period covered by this book, the gold scudo was worth 45 sous in France, 70 soldi in Ferrara and 105 baiocchi in Rome.

To simplify the bewildering number of currencies that appear as a result of Ippolitos extensive travels, I have translated all prices into gold scudi, only occasionally using the local currency to clarify exchange rates.

Introduction

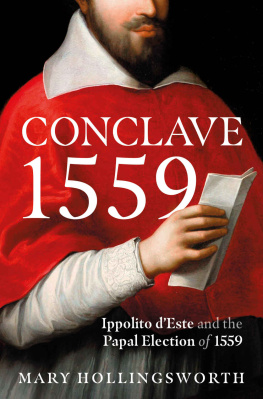

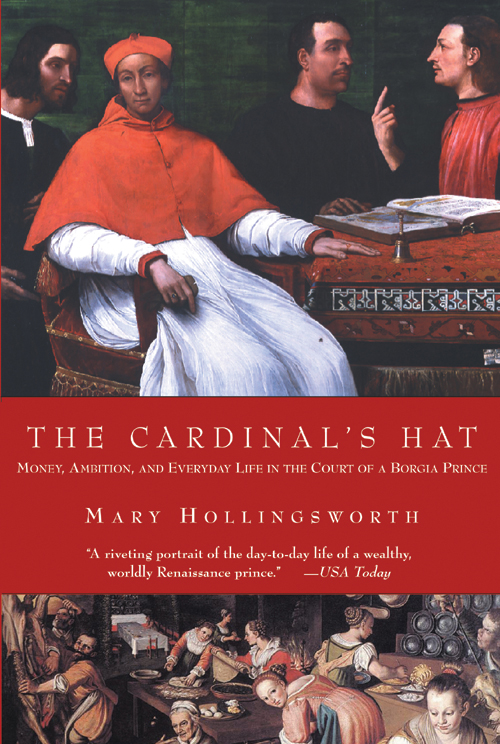

The Archives at Modena

I PPOLITO DESTE WAS the second son of Alfonso dEste and Lucretia Borgia. His grandparents on his fathers side were Ercole dEste, the Duke of Ferrara, and Eleonora of Aragon, daughter of the King of Naples. Lucretias parents were Rodrigo Borgia, better known as Pope Alexander VI, and his beautiful Roman mistress, Vanozza de Cataneis. Ippolitos lineage was impressive, and so was his career. One of the leading cardinals of the sixteenth century, and a serious contender for papal election on several occasions, he was also one of the most important patrons of the arts in Rome, the builder of the magnificent Villa dEste at Tivoli and the benefactor of the musician Palestrina. His artistic achievements have been thoroughly researched by scholars but his life and career have so far largely been ignored. This is surprising considering the astonishing quantity of his papers that have survived. The state archives at Modena contain over 2,000 of his letters, as well as many written to him, and over 200 of his account books. As one particular friend, Julian Kliemann, pointed out to me, Ippolito would be a fascinating subject for research.

Even so, I kept putting off my visit to the archives in Modena until I was finally forced there by accident. One freezing morning in January 1999 I was negotiating the fog-bound autostrada north of Turin, on my way back to Florence where I was living at the time, when my landlady rang to say that my central heating had broken down. The weather was far too cold to consider going home and the Modena exit was only two hours away. The next day I went to the archives. They are housed in what had been a very grand palace. There was a car parked between the columns of the entrance hall, and what had once been an elegant courtyard was now a kitchen garden.

Once the staff realized that I wanted to look at all Ippolitos papers, they could not have been more helpful. The Director sent me down into the stores, the cavernous reception rooms of the old palace, now musty and cold, and lined with shelves filled with leather-bound volumes, acres and acres of the Este familys past, dating back to the fourteenth century. For a historian, this was heaven. I found Ippolitos account books stacked high up in a corner under one of the ceilings, accessible only by a narrow metal ladder. For the following three months I sat in the little reading room upstairs and immersed myself in the minutiae of Ippolitos life as I read through the volumes of accounts and box upon box of papers.

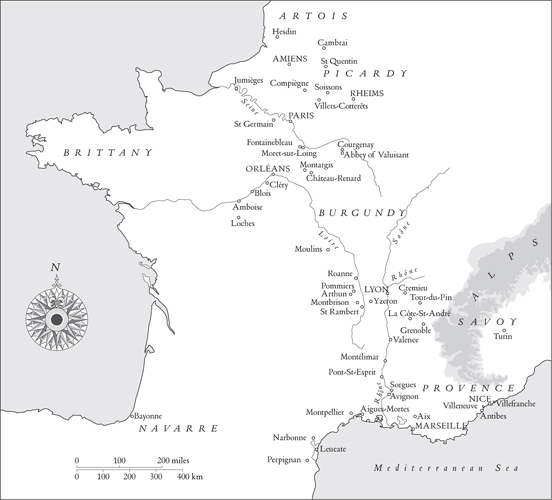

Floodwater had damaged many of the letters some crumbled in my hands, while others were legible only under the ultra-violet light of the lamp by the photocopying room. But a surprising quantity were as clear as the day on which they had been written, 450 years ago. Neither the language nor the handwriting were as hard to decipher as I had feared. Unlike English, Italian has changed little since the sixteenth century, though it took some time to get used to the local dialect, and to the bewildering variety of currencies Ippolito encountered as he travelled across Italy and France. Some hands were impossibly cramped, but others wrote in a perfectly formed italic script. Much harder were the coded letters, several of which I have still not managed to decipher.

As the days progressed I gradually discovered Ippolito himself, his habits, his tastes and his personality, embodied in the large, open and exuberant signature which he penned at the bottom of each of his letters. However, it was not just Ippolito who began to emerge across the centuries, but also the bookkeepers who meticulously filled in his ledgers, the men who belonged to his household and were listed year after year in the registers of salaried employees, the shopkeepers who supplied the velvets, silks and taffetas for his clothes, the painters who decorated his palaces, the butchers who provided the meat for his kitchens, and the blacksmiths who supplied his horses with shoes.

What I had stumbled upon was a unique account of life in sixteenth-century Europe, a detailed record of how a Renaissance prince lived. Here were not only the gold and silver, the silks and velvets, the fripperies and baubles that we associate with pomp and prestige, but also the soap, the candles, the shoelaces, the cooking pots and the drains, the stuff of everyday life. Above all, these ledgers bore witness to one of the major preoccupations of the period, and something much loved by Ippolito money.