CONCLAVE

1559

CONCLAVE

1559

Ippolito dEste and the

Papal Election of 1559

MARY

HOLLINGSWORTH

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

First published in 2021 by Head of Zeus Ltd

An Apollo book

2021 Mary Hollingsworth

The moral right of Mary Hollingsworth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders for permission to reproduce material in this book, both visual and textual. In the case of any inadvertent oversight, the publishers will include an appropriate acknowledgement in future editions of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN [ HB ] 9781800244733

ISBN [ E ] 9781800244726

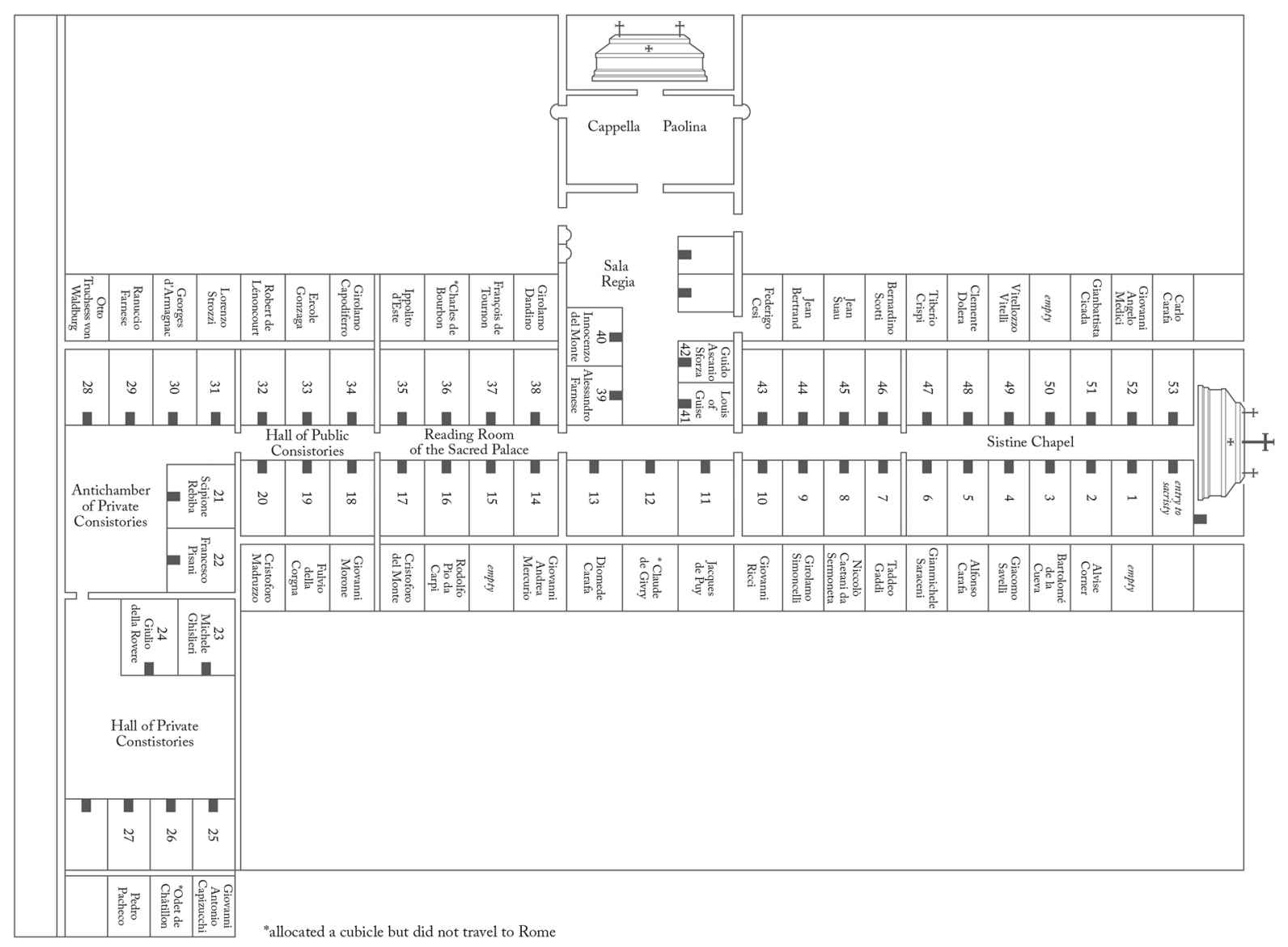

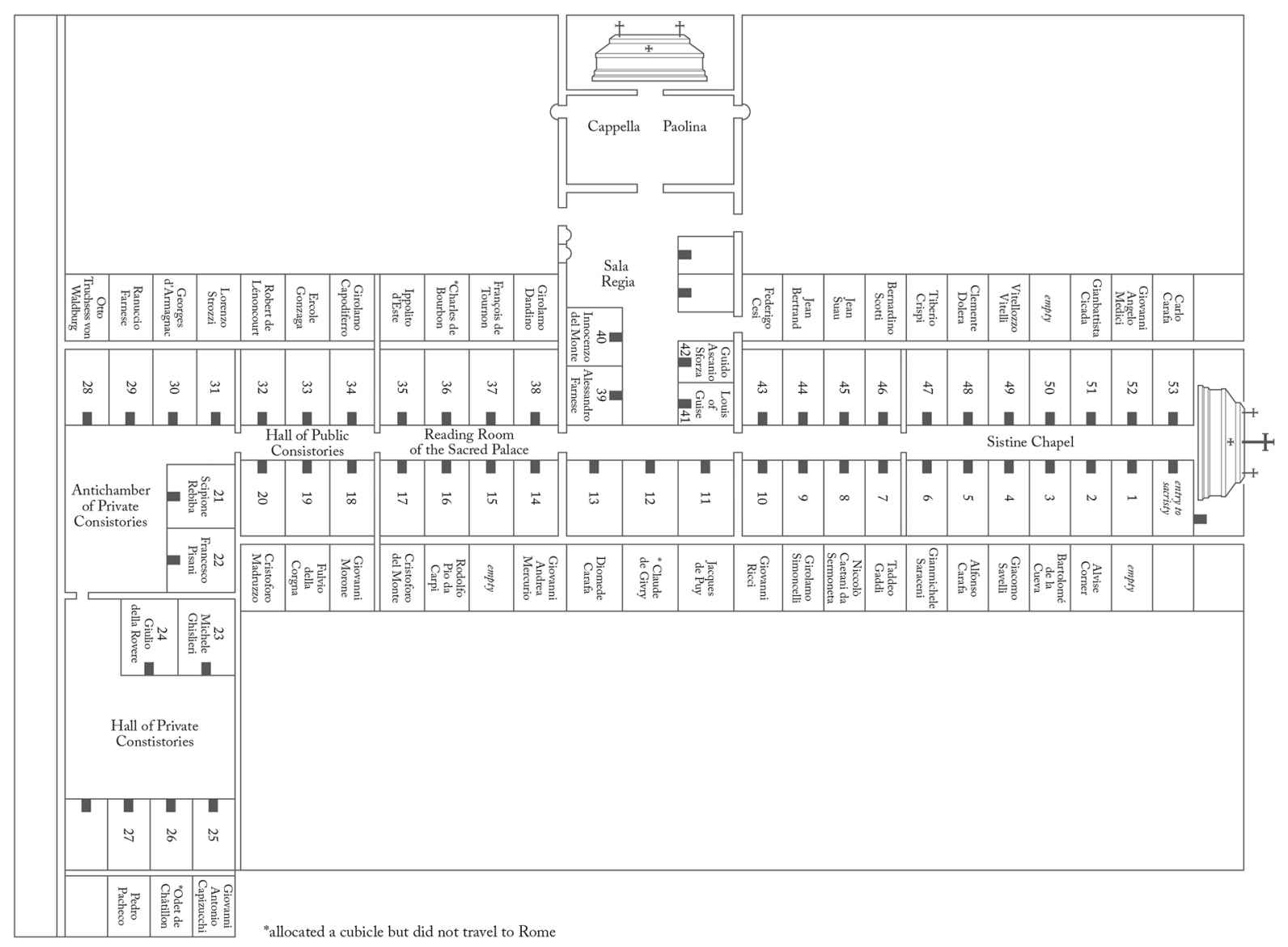

Conclave illustration by Jeff Edwards

Head of Zeus Ltd

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

To Flora Mary Saywell

CONTENTS

See also

The relationship between the various currencies that appear in Ippolitos account books is complex. First of all, most states in sixteenth-century Europe had their own silver-based currency. In France, a centralized monarchy, there was a single system based on the livre (1 livre = 20 sous = 240 deniers ). In Italy each of the peninsulas many independent states had their own local currency. Ferrara, for instance, used the lira marchesana (1 lira = 20 soldi = 240 denari ); Rome by contrast preferred a decimal system based on the scudo di moneta (1 scudo di moneta = 10 giulii = 100 baiocchi ). There were also internationally recognized gold currencies, notably the Venetian ducat, the Florentine florin or the gold scudo. The latter appears frequently in Ippolitos ledgers and was evidently used across Europe. These currencies, both gold and silver, fluctuated against each other in response to market forces. The period covered by this book, 155965, was one of significant inflation in Ferrara, where the price of a gold scudo rose from 73 to 78 soldi ; by contrast, in Rome its value remained steady at 110 baiocchi over the same period. In France, despite the economic hardship caused by the religious wars, its value rose only slightly from 48 to 49 sous over the two years Ippolito spent there, from 15613. To simplify this I have translated most of the prices in this book into gold scudi, although I have needed to use the Roman baiocchi to clarify relative details about the cost of food.

Ferrara

S UMMER 1559

The summer of 1559 had been unusually hot in Ferrara. By the middle of July the broad waters of the Po had sunk to little more than a sluggish stream, barely capable of bearing the barges bringing the newly harvested crops of wheat, barley and spelt down to the granaries in the city. Cardinal Ippolito dEste sought relief from the sweltering heat in his country villas, entertaining his friends and family at small dinner parties, the tables laden with delicate dishes prepared by his chefs, and plenty of salads and fresh fruit peaches, figs and melons were all in season, and Ippolito was particularly partial to melons. Their leisurely dining was accompanied by the music of his singers, lute players and flautists, though without Jacques, his sensational castrato who had returned home in May. It was too hot to do anything energetic and Ippolito passed the time gambling at cards, gossiping and making plans with his brother Ercole, Duke of Ferrara, for the autumn hunting season. An enviable life of luxury and ease, you might think, but this idleness was not of Ippolitos choice. Since acquiring his red hat back in 1539, he had worked hard to establish himself as one of the most powerful figures at the papal court. For the last four years his glittering career had been at a standstill after he was abruptly exiled by Pope Paul IV and forced to retire to the provincial backwater of his family estates in Ferrara.

Ercole and Ippolito belonged to Italys old aristocracy. The eldest sons of Duke Alfonso I and his infamous duchess, Lucrezia Borgia, they had a sister, Eleonora (who was abbess of the convent of Corpus Domini in Ferrara where she had care of the parental tombs), a younger brother, Francesco, and two half-brothers born to their fathers mistress whom he married after Lucrezia died. Ercole had been a young man when he inherited the title in 1534; now a staid fifty-one-year-old, he had proved a good, if somewhat cautious, ruler. His father had secured him a prestigious bride: in 1528, hed married Rene of France, the daughter of Louis XIII and aunt to the present king, Henri II. She had given birth to five healthy children, two sons and three daughters. The eldest, Anna, was married to Francis, Duke of Guise and one of Frances premier nobles, whose niece better known to us as Mary, Queen of Scots was married to the dauphin. Duke Ercoles heir Alfonso, now twenty-five years old, had recently married Lucrezia de Medici, the daughter of Cosimo I, Duke of Florence, but in the summer of 1559 he was abroad on an extended visit to the French court, leaving his young bride behind with her family. His younger brother, Luigi named for their royal grandfather Louis was destined for the Church. Thanks to the influence of their uncle Ippolito, Luigi had secured the position of Bishop of Ferrara in 1550 at the age of just twelve, but his career too was on hold while the cardinal remained in disgrace in Rome.

Despite the heir and the spare, Ercole and Renes marriage was not happy. Her royal blood may have cemented the ties between Ferrara and France, and linked her children to the French crown, but she had caused much embarrassment to her husband by converting to Protestantism. In 1554, under pressure from Paul IV and the Inquisition, the Duke had been forced to make her repudiate her heretical beliefs in public, and to insist on her attendance at mass in Ferrara Cathedral on important feast days. She did her duty reluctantly and continued to worship as a Protestant in the privacy of her own apartments; the Duke, worried about her influence on their two young daughters, sent the girls to the care of his sister Eleonora at Corpus Domini. Remarkably, despite his position in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, Ippolito was far less fazed by his sister-in-laws choice of faith and the two of them, who had been friends for a long time, continued to remain close.

Ippolito himself was a year younger than his brother (his fiftieth birthday, on 25 August 1559, was imminent) and he too was a grandfather. His mistress had borne him a daughter in 1536 and he had named her Renea after his sister-in-law. In 1553 Renea married the lord of Mirandola, a local landowner, and had recently given birth to a daughter whom she affectionately named Ippolita. Among Ippolitos account books is one detailing the expenses incurred in buying Reneas trousseau, which came to the huge sum of 3,000 scudi, more than six months salary for his household.