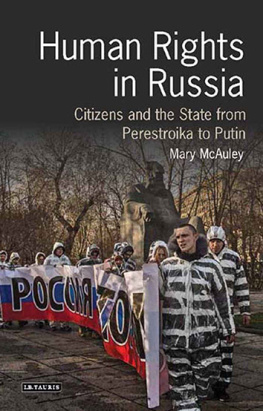

MARY MCAULEY has been engaged with the Russian human rights community for the past 20 years as a grant maker, consultant and analyst. She is the author of several books on Russian politics, including Russias Politics of Uncertainty and Soviet Politics 1917-1991, and, more recently, of Children in Custody: Anglo-Russian Perspectives. She taught politics at the universities of Oxford and Essex, before becoming the head of the Ford Foundations office in Moscow, with particular responsibility for human rights and legal reform.

This is a highly informative account of an important and interesting topic. It charts the development of human rights in Russia, from the disintegration of the USSR to recent times. Written by an internationally renowned specialist of Russia who has extensive first-hand experience of Russian domestic politics and the development of civil society after communism, it uses that experience and a large number of interviews with Russians engaged in the field to chronicle the rocky development of human rights organizations in Russia.

Margot Light, Professor Emeritus of International Relations,

London School of Economics and Political Science

HUMAN RIGHTS

IN RUSSIA

Citizens and the State from Perestroika

to Putin

M ARY M C A ULEY

This book is dedicated to the memory of Valery Abramkin, penal reformer,

to Liudmila Alekseeva, with affection, and in admiration for her

indomitable spirit, and to the activists of an undaunted and resourceful

younger generation.

Published in 2015 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2015 Mary McAuley

The right of Mary McAuley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part

thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book.

Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

Library of Modern Russian History 1

ISBN: 978 1 78453 125 6

eISBN: 978 0 85773 931 5

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

. Living chain around KGB headquarters, Lubyanka Square, on the first Political Prisoners Day, 30 October 1989. (Dmitry Borko)

Protester from Demsoiuz is led away from the 30 October 1989 demonstration. (Dmitry Borko)

Requiem for dead soldiers organized by Mothers Right, 1994. (Dmitry Borko)

Svetlana Gannushkina of Migration Rights meeting with Yezidis, refused citizenship, in Krasnodar in 2005. (Gannushkina archive)

Domestic violence poster of the early 2000s, used by ANNA.

Poster used by Mothers Right, 2010.

Liudmila Alekseeva and Nina Tagankina (Moscow Helsinki Group) debate their right to hold a public meeting in Pushkin Square with law enforcement officers in 2007. (Varvara Pakhomenko)

Court hearing of Bolotnoe demonstrators, Black Friday, Moscow, February 2014. (Aleksander Baroshin)

Demonstrators outside the court are removed by OMON (Special Services). (Aleksander Baroshin)

March in St Petersburg protesting against the new law prohibiting discussion of LGBT issues with minors, 2013. (Dmitry Musolin)

Putin meeting with activists, January 2014, to discuss appointment of a new ombudsman. On the right is Alekseeva, on the left, Babushkin and Gannushkina. Vladimir Lukin, the outgoing ombudsman, is far right, opposite Elena Topoleva of the Civic Chamber. (RIA Novosti)

Sergei Kovalev, International Memorial Society. (Irina Flige)

Liudmila Alekseeva, Moscow Helsinki Group. (RIA Novosti)

Arseny Roginsky, International Memorial Society. (Irina Flige)

Lev Ponomarev, For Human Rights and Liudmila Alekseeva. (Varvara Pakhomenko)

Oleg Orlov, Memorial Human Rights Centre (with poster of Natalya Estemirova, murdered in Grozny in 2009). (Mindaugas Kojelis, web-editor European Parliament)

Valery Abramkin, Moscow Centre for Prison Reform. (AFP, Telegraph 2 May 2013)

Svetlana Gannushkina, Civic Assistance Committee, Migration Rights. (Irina Flige)

Boris Pustintsev, Citizens Watch. (Vladislav Shinkunas)

Andrei Blinushov, Memorial Society, Ryazan. (Irina Flige)

Igor Kalyapin, Committee Against Torture. (World Organization Against Torture)

Igor Averkiev, Perm Civic Chamber. (Irina Flige)

Grigory Shvedov, Caucasian Knot. (Ford Foundation Archive)

Marina Pisklakova, ANNA. (Ford Foundation Archive)

Pavel Chikov, Agora. (Pavel Chikov)

Tanya Lokshina, Human Rights Watch. (Tanya Lokshina)

Maria Kanevskaya, Human Rights Resource Centre. (Maria Razumovskaya)

PREFACE AND

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book about activists, many of whom are defending unpopular causes, is a hazardous undertaking. And when the author is an outsider, albeit a sympathetic outsider, and the topic is defending rights in Russia today, the hazards increase. Some of the activists will feel I lack an understanding of their Russia, that my criticisms are misplaced; others, observers from the wider community, that I am too sympathetic towards them. Some Western scholars will argue that I overestimate the significance of the human rights community; others, including activists, will take issue with my view of human rights. Perhaps too I should have written one book for my Russian colleagues, another for the Western reader. All I can do here is to acknowledge my debt to all who have contributed, one way or another, to this book, a book that crosses disciplines, has elements of a personal memoir, is written not only for students and scholars but also for a wider readership of those with an interest in Russia or human rights.

A further acknowledgement is in order, and that is to the legacy left by a lifetime engagement with Russia. Whether that is for good or bad, is another matter. In generation terms I fall into the category known in Russia as the people of the sixties, those who were young adults when Khrushchev advanced his destalinization campaign in 1956, and that inescapably has a bearing on the way I viewed and view the changes since 1991. I first visited Russia in 1959, as a student, then spent 19613 as a visiting graduate student at the labour law department, in the law faculty at Leningrad (now St Petersburg) University. Neither politics nor sociology existed as a discipline then (nor, one might add, did sociology exist at Oxford University). This was the time of the New Left. I chose the settlement of labour disputes as my thesis topic. I spent time in the factories and in the district courts. Thereafter I studied and taught Soviet politics and history in the UK and in the USA, returning for research periods to Leningrad.

In 1990 Russia opened up, unbelievably, and for the first time I could travel where I pleased, stay where I pleased, talk to anyone and everyone. With British Academy support, and academic leave, I spent most of 19914 researching the changing political scene, travelling from Siberia to Tatarstan, from the Urals to Krasnodar in the south, Arkhangelsk in the north, and back to St Petersburg. I kept a diary. Sometimes my path crossed with individuals who would subsequently set up a human rights organization, but I do not remember participating in any discussions on human rights in Russia before 1995. But, then, I had never been particularly interested in the topic. I had never read the Universal Declaration, nor the conventions. Membership of Amnesty International did not include discussions of human rights, only those of political prisoners. As for so many in Russia at the beginning of the nineties, it was the democratic movement and its opponents, the new political parties, and the economic collapse that occupied all my attention.

Next page