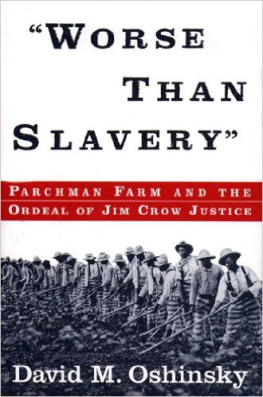

Worse Than Slavery

PARCHMAN FARM AND THE ORDEAL OF JIM CROW JUSTICE

DAVID M. OSHINSKY

FREE PRESS PAPERBACKS

Published by Simon & Schuster

New York

FREE PRESS PAPERBACKS

A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 1996 by David Oshinsky

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

First Free Press Paperbacks Edition 1997

FREE PRESS PAPERBACKS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Designed by Carla Bolte

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oshinsky, David M., 1944

Worse than slavery: Parchman farm and the ordeal of Jim Crow justice/ David M. Oshinsky.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Mississippi State PenitentiaryHistory. 2. Criminal justice, Administration ofMississippiHistory. 3. PrisonersMississippiHistory. I. Title.

HV9476.M72M576 1996

365.9762dc20 95-52880

CIP

ISBN-13: 9780684830957

eISBN-13: 978-1-439-10774-4

ISBN-10: 9781439107744

ISBN-13: 978-0-684-83095-7 (Pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-684-83095-7 (Pbk.)

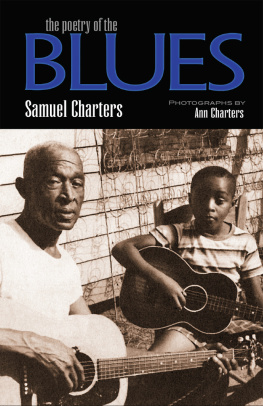

Grateful acknowledgment is made of permission to reproduce illustrations from the following sources: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, pages 2, 7-9, 10(top), 11-13, and 15; Library of Congress (Documentary Portrait of Mississippi: The Thirties, edited by Patti Carr Black, 1982), pages, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (top); archives of Parchman Penitentiary, pages 1, 10 (bottom), and 16; Samuel Charters, The Blues Makers, 1991, page 14.

www.SimonandSchuster.com

FOR MY SON MATTHEW, a fathers jewel

The abuses of [our criminal justice] system have often been dwelt upon. It had the worst aspects of slavery without any of its redeeming features. The innocent, the guilty, and the depraved were herded together, children and adults, men and women, given into complete control of practically irresponsible men, whose sole object was to make the most money possible.

Frank Sanborn, keynote address, in Ninth Atlanta Conference on Negro Crime (edited by W. E. B. Du Bois), 1904

The convicts condition [following the Civil War] was much worse than slavery. The life of the slave was valuable to his master, but there was no financial loss if a convict died.

L. G. Shivers, A History of the Mississippi Penitentiary, 1930

The most profitable prison farming on record thus far is in the State of Mississippi which received in 1918 a net revenue of $825,000. Given its total of 1,200 prisonersand subtracting invalids, cripples, or incompetentsit made a profit over $800 for each working prisoner.

Proceedings of the Annual Congress of the American Prison Association, 1919

I have visited Parchman repeatedly and I have found that their cotton was very profitable but that profit was secured by reducing the men to a condition of abject slavery.

Hastings Hart, reporting to the Russell Sage Foundation, 1929

On the whole, the conditions under which prisoners live in [Parchman], their occupation and routine of living, are closer by far to the methods of the large antebellum plantation worked by numbers of slaves than to those of the typical prison.

David Cohn, Where I Was Born and Raised, 1935

One hes a gitten de leather,

Two he dont know no better,

Three cry niggah, stick yo finger in yo eye,

Four niggah thought he had a knife,

Five got hit offn his visitin wife,

Six now hell git time for life,

Seven lay it on trusty man!

Eight wham! wham! he gotta wuk tomorra,

Nine he gotta chop cotton in de sun,

Ten dats all, trusty men, yous done.

The cadence of Black Annie, the strap used at Parchman Farm

Self-supporting prison systems must, in the end, become slave camps. Slavery is the partner of the lash. The wielder of the lash is brutalized along with the victim, and brutes will sometimes kill.

Southern Regional Council, The Delta Prisons: Punishment for Profit, 1968

Contents

Acknowledgments

This project began in the reading room of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jacksona wonderfully supportive environment. I would like to thank Hank Holmes, Nancy Bounds, and the reference staff for making a northerner feel very much at home. I am especially grateful to Anne Lipscomb Webster for her skill, her interest, and her boundless energy. I am indebted as well to archivists at the University of Mississippi Library; the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; the Library of Congress; and the Barker History Center at the University of Texas, Austin.

A number of Mississippians provided support along the way. Jan Hillegas generously shared her research on lynchings and executions. Attorney Ron Welch took me to Parchman, tutored me about prison issues, and showed me the finer side of Southern life and banjo-picking. Vera Richardson helped me gather research material. Jim Young and Ed King filled in crucial gaps about Parchman and civil rights. Parchman officials Dwight Presley and Gene Meally supplied valuable information about the prison; Lieutenant Tony Champion was a superb guide; and longtime inmates James Louis, Robert Phillips, Horace Carter, Delbert Driskill, and Matthew Winter offered remarkable first-hand testimony about convict life.

I would also like to acknowledge Rutgers University for supplying research and travel funds during the life of this project, and the National Endowment for the Humanities for its generous senior fellowship. At Rutgers, my close friends and generous colleagues, Willam ONeill and Maurice Lee, were a source of strength for me in difficult times, and Chris Stacey did superb work as a research assistant.

At The Free Press, I have had the rare pleasure of working with a fine copy supervisor, Loretta Denner, as well as with two superb editors and good friends. Joyce Seltzer played the major role in getting this book off the ground. Her enthusiasm was contagious; her patience more than I deserved. When Joyce left for Harvard University Press, Bruce Nichols stepped in and brought the book to conclusion. I owe Bruce, in particular, a debt of gratitude that he alone understands.

My agent, Gerry McCauley, provided encouragement, support, and friendship in expert doses. He has the overwhelming respect of the authors he represents because of the personal and professional interest he takes in their lives.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my parents for their love and endless generosity; my children, Matthew, Efrem, and Ari, for the joy they provide and the patience they have shown; and Jane Rudes, for making my daily life brighter in more ways than I can possibly listor repay.

Prologue

Northerners, provincials that they are, regard the South as one large Mississippi. Southerners, with their eye for distinction, place Mississippi in a class by itself.

V. O. Key, Jr.

I

Throughout the American South, Parchman Farm is synonymous with punishment and brutality, as well it should be. Parchman is the state penitentiary of Mississippi, a sprawling 20,000-acre plantation in the rich cotton land of the Yazoo Delta. Its legend has come down from many sources: the work chants and field hollers of the black prisoners who toiled there; the Delta blues of ex-convicts like Eddie Son House and Huddie Leadbelly Ledbetter; the novels of William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Shelby Foote, and, most recently, John Grisham, who seem almost mesmerized by the mystique of the huge Delta farm. One of Faulkners characters in