Conclusion: No Excuses

O N NOVEMBER 5, 2014, all of Newark seemed to stand still and stricken as word spread of the untimely death of its civic steward, Professor Clement Price, at age sixty-nine from a massive stroke. In a stirring eulogy at Prices funeral, Mayor Ras Baraka said the city already missed the sound of his distinct, calming voice... forcing all of us to deal with each other, to see each other in one collective narrativeour storyour Newark.

Newark needed that voice more than ever amid the polarizing rancor over education. In an interview shortly before he died, the usually optimistic Price had delivered a grim summation of the reform effort. At the outset, he said, this was an opportunity, I thought, to put public education at long last at the center of Newarks civic agenda. I think that opportunity was lost. There was a huge consensus here that schools needed dramatic reform. Now the space for that conversation has almost disappeared.

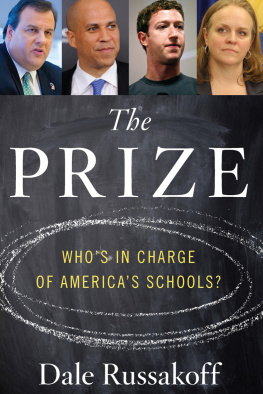

For four years, the reformers never really tried to have a conversation with the people of Newark. Their target audience was always somewhere else, beyond the people whose children and grandchildren desperately needed to learn and compete for a future. Booker, Christie, and Zuckerberg set out to create a national proof point in Newark. There was less focus on Newark as its own complex ecosystem that reformers needed to understand before trying to save it. Two hundred million dollars and almost five years later, there was at least as much rancor as reform.

Newark illustrated that improving education for the nations poorest children is as much a political as a pedagogical challenge. Redirecting large district bureaucraciesfor decades, the employers of last resort in distressed citiesin the service of children in classrooms is a treacherous process, activating well-organized public workers, political organizations, and unions invested in the status quo. Voter backlashes against education reformers in mayoral elections in New York City in 2013, in Newark in 2014, and in Chicago in 2015 revealed the tenuous nature of disruptive changes made without buy-in from those who have to live them.

Howard Fuller, the former Milwaukee superintendent and the first African American to become prominent in the education reform movement, happened to pass through the city in the fall of 2014 on a promotional tour for his memoir, No Struggle, No Progress. He literally cringed at the political spectacle that reform had fostered. I think a lot of us education reformersand I include myselfhave been too arrogant, he said. Its not even what you do sometimes, its the way you treat people in the process of doing it. If your approach is to get a lot of smart people in the room and figure out what these people need and then we implement it, the first issue is who decided that you were smart? And why do you think you can just get in a room and make decisions for a community of people? You dont think theyll respond the way they responded? Im not saying you can ever create this level of change without resistance, but I dont see how this is politically sustainable over time.

Even in the aftermath of the uprising against One Newark, Chris Cerf, the states chief architect of the Newark effort, said he had no regrets about imposing changes unilaterally. A more inclusive process, he said, would not have yielded as much progressin particular, more schools run by high-achieving charter networks. You have no chance of giving these kids the lives they deserve if you dont essentially override the local political infrastructureno chance at all, he said. I honestly dont think theres a logic-based counterargument to that... Theres no chance this political culture would have been able to rise above the question of who gets what. They had their chance.

But a year later, in the summer of 2015, the state announced a sudden and stunning change of strategy. Despite his plummeting popularity, Christie was making a run for the White House. Opposition to Anderson and her agenda was drawing national attentionwith more than one thousand students marching out of class and into downtown traffic, teachers refusing to carry out her latest reforms, and Baraka taking his fight for local control to the New York Times op-ed page. In early June, Christie covertly invited Baraka to Trenton to discuss education. Days before his formal campaign launch, the Republican governor and the Democratic mayor issued a joint announcement that they had reached an agreement to begin the process of returning to Newark long-lost control over its public school district. Anderson was not the person to lead in this new era, the governor said. She was given three hours to decide whether to resign or be fired. She resigned. I dont blame Cami at all for coming to the decision that we did that it was time for her to move on, Christie told reporters. Andersons former patrons moved quickly to write her out of the narrative of school reform in Newark. She came here, she gave service, and shes now moved on, Booker said.

There was a sense of dj vu all over againthe white Republican governor and Newarks black Democratic mayor coming together to fix the public schools, declaring in a joint statement, The future of our children deserves no less. And to complete the tableau, Christie announced the new superintendent would be the founding leader of the reform effortChris Cerf, who just had left his job at the education technology firm headed by Joel Klein.

But this Newark mayor was certain to be a very different partner for the state than Booker. And now Baraka was tantalizingly close to reclaiming Newarks prize. Still, there were legislative and regulatory hurdles to be cleared, which meant Cerf would remain in charge for at least a year, probably longer. A committee with five members appointed by Christie and four by Baraka would oversee the process. Cerf sent signals immediately that he was committed in the interim to pushing ahead with the agenda of charter school expansion, citywide school choice, and increased teacher responsibility, but he also made clear he was ready to compromise on at least some grassroots concerns about One Newark. There were suggestions that Baraka would get some of his own brand of reformslike community schools, with social services for families and neighborhoods as well as studentsfinanced with some of the Zuckerberg bounty that Anderson hadnt spent. Indeed, since Barakas election, some of Zuckerbergs remaining dollars had begun flowing to community-based initiativesthe mayors summer youth-employment program, a citywide campaign to increase the college graduation rateinstead of systems reforms, a shift long sought by the staff of the Foundation for Newarks Future but only recently embraced by its board. The voices of Newark, it appeared, were beginning to be heard.

While praising the new direction of FNF, Baraka declared himself unmoved by Cerfs newly conciliatory demeanor, calling his appointment a clear indicator that Governor Christie is still Governor Christie, and we should not expect anything to the contrary of him. He added, We are in this fight to govern and be in charge of our lives. The Governor should expect nothing less from Newark.

Cerf appeared to be following the lessons of Washington, D.C., where Michelle Rhees autocratic leadership gave way in 2010 to a far more collaborative chancellor in Kaya Henderson. She pursued an agenda similar to Rhees and closed fifteen schools in 2013, but only after a yearlong vetting process with affected families, making multiple changes in response to their input. She also presided over slow, but steady, achievement gains. While the backlash against Rhee fueled the ouster of Washingtons mayor in 2010, the city elected a new mayor in 2014 who promised to keep Henderson in office. Movements that dont include beneficiaries are doomed to fail, Henderson said.