A River Runs Again

Copyright 2015 by Meera Subramanian

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Illustrations provided by the author

Book design by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Subramanian, Meera.

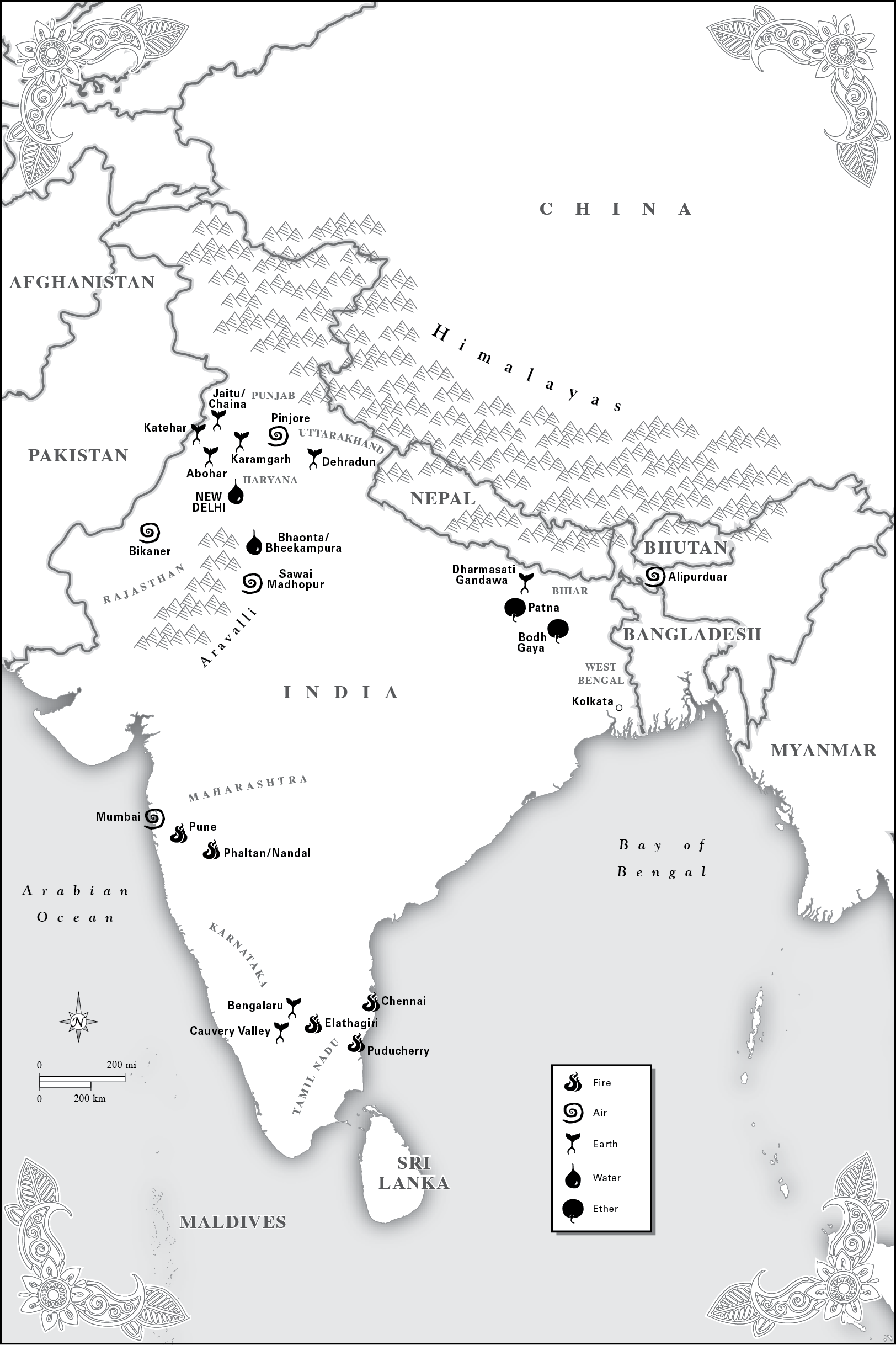

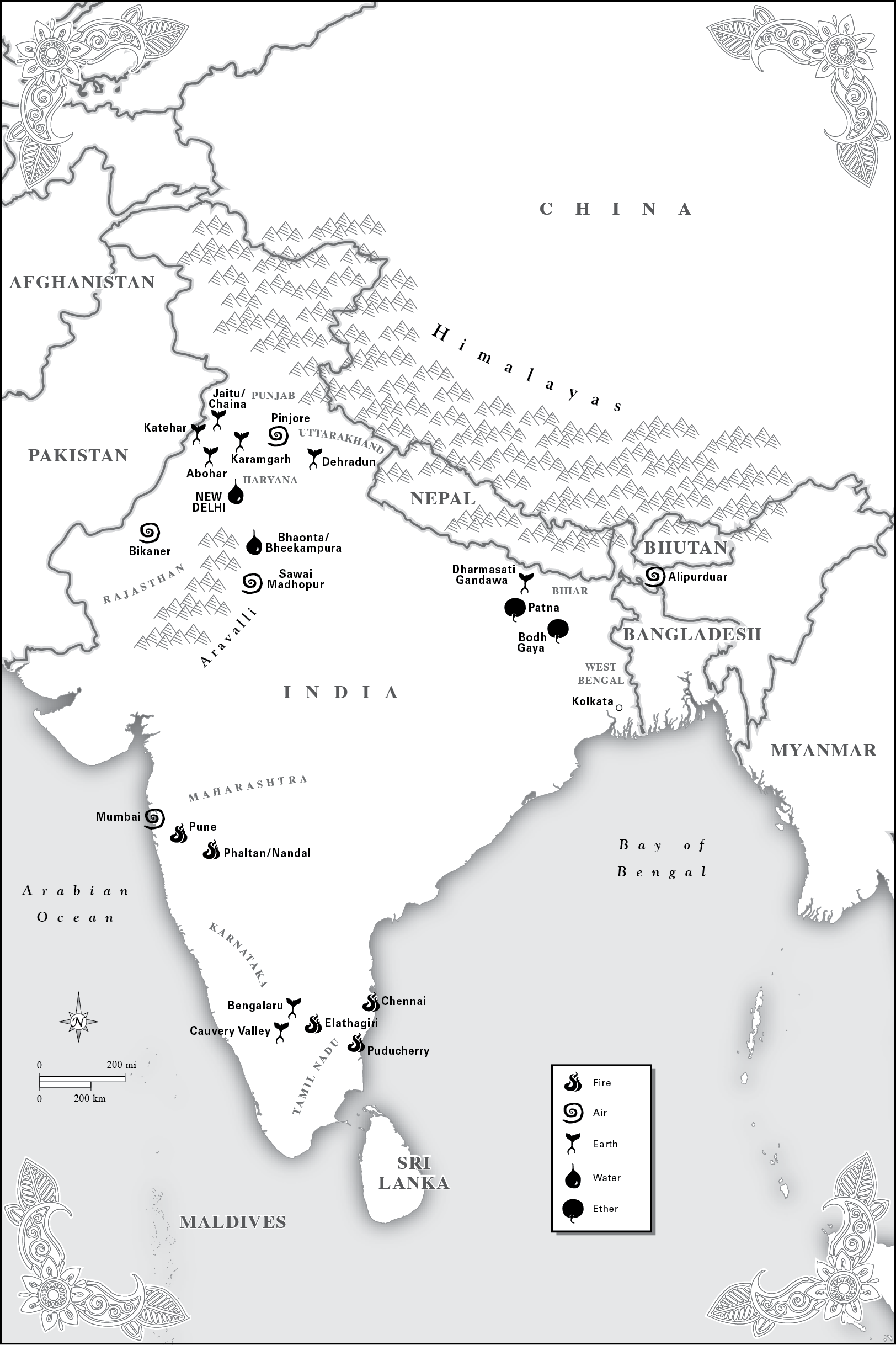

A river runs again : Indias natural world in crisis, from the barren cliffs of Rajasthan to the farmlands of Karnataka / Meera Subramanian.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61039-530-4 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-61039-531-1 (e-book) 1. Environmentalism--India.

2. Environmental protection--India--Citizen participation. 3. Small business--Environmental aspects-

India. 4. Small business--Social aspects--India. 5. India--Environmental conditions. 6. Environmental

policy--India. I. Title.

GE199.I4S83 2015

363.700954--dc23

2015014343

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to my parents, Mani and Ruth Subramanian

Life,

When elements become ordered, thats all.

Death,

But a moment when into chaos they fall.

Brij Narain Chakbast, Urdu poet

Contents

When he was little more than a boy in Madras, my father learned of the family astrologers prophesy that he would grow up and one day cross the Kala Pani, the demon-filled Black Waters that separate India from the rest of the world. Hindus, especially high-caste Brahmins, were forbidden to traverse such divides, yet the prediction came true. When he was twenty-five, my father became the first in his family to leave South Asia. He traveled by ship for three weeks and a day before arriving in New York Harbor. It was 1959, and he planned to stay for eighteen months in pursuit of a masters degree in engineering. Five years later, he had acquired a PhD, to his familys delight, and an American wife, to their distress. He was part of that first trickle of Indian immigrants that would grow into a flood, and his union with my mother was representative of what would become, a half century later, an intimate link between cultures. Then, Asian-Indian wasnt even a category on the US Census. By 2014, yoga had become a common American pastime and a visit from the Indian prime minister could pack Madison Square Garden in the heart of Manhattan.

After my brother and I were born, my father took all of us to Madras to meet his family. Though I was too young to remember that first visit, the arms of aunties and grandparents who cradled me surely imprinted, and I still remember exquisite details from later trips. My fathers vast clan in Indiato whom I was closer than to the small scattering of American relatives of European descent on my mothers sidesowed the seeds of my interest in Indias natural history and her people. Their faraway influence broke through the thick crust of my otherwise insular suburban upbringing in New Jersey (malls! rock concerts!), where my parents had settled to raise my brother and me.

On each trip to India, I gathered impressions. There were the seeds of the mehendi plant whose leaves an aunt ground into a paste to decorate my hands for a cousins wedding when I was ten. There were seeds that grew into the limes I plucked from an uncles front yard in Alwarpet to make fresh juice at his house when I was thirteen. And there were those from the neem tree whose upper branches my grandmother reached for from her balcony and used to craft me a toothbrush when I was nineteen. Maybe it was these seeds that planted in me a desire to leave the race of the upwardly mobile Northeast and landed me at the end of a dirt road in Oregon by the time I was twenty-six.

Aprovecho Research Center, the environmental nonprofit where I lived and worked for nearly a decade, was composed of an eclectic team of idealists, hungry for knowledge. Much of the forty-acre land trust was a forest where we collected the wood to build and warm our homes and to cook the food we grew organically. We harvested electricity from the sun with a solar array and built a small dam to trap water from a spring. Both a school and research center, Aprovecho drew people from around the world to teach and learn the skills of sustainability.

But just as I was turning my back on consumerism, living deliberately in developing-world style on the edge of my developed nation, Indians were getting their first real taste of material wealth and wanted more.

In the summer of 1991, India launched initiatives that opened its economy to the world. The result was a rapid blooming, as awkward and astounding as human adolescence. After nearly half a century as a borderline socialist nationwith one inept state airline and two types of cars to which you could affix a Be Indian Buy Indian bumper stickerthis still young country had vaulted into the global economic fray. The once wealthy Bird of Gold, as it was called before centuries of colonial rule plucked her bare, was again poised to soar. Analysts predicted that the worlds largest democracy would soon outpace China economically and become the fifth-largest consumer market by 2025with a middle class that would exceed the entire population of the United States. As the United States and European Union struggled to regain their economic footing after the 2008 economic crisis, the BRICSBrazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africacontinued to rise, with India leading the way. That Western power will remain intact, wrote Patrick French in India: A Portrait, in 2011, is an outdated and fantastic view.

But as India travels on this path of progress, masses of Indian citizens are being left behind, and the lands and waters that have sustained Indias people for millennia are beyond compromised. Since achieving independence in 1947, Indias population has tripled. While a rapidly growing middle class has gained unprecedented material comforts, only a tiny fraction of Indians can afford to shop at the glitzy air-conditioned malls springing up across the country. Today the vast majority of Indians still struggle to meet fundamental daily needs. Six out of ten citizens lack access to clean water, a third live beyond the glow of the electric grid, and less than half have access to a toilet. More than two-thirds of households cook over an open fire, and the food they prepare there is inadequate: nearly half of all children under five are stunted, and the rate of malnutrition currently exceeds that of sub-Saharan Africa.