Table of Contents

For Jakob Glen Thornton

Incipe parve puer risu cognoscere matrem

Acknowledgments

The idea for this book arose from many conversations with Victor Davis Hanson, from whose expertise and friendship I have long benefited. Roger Kimball once more has been generous with his encouragement. The bulk of this book was written with the financial support of the Hoover Institution, where I was a 2009-2010 Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National Fellow and the Susan Louise Dyer Peace Fellowship National Fellow. As always, I am grateful for the love and patience of my wife, Jacalyn.

Introduction

The Temptation of Hector

But waitwhat if I put down my studded shield

And heavy helmet, prop my spear on the rampart

And go forth, just as I am, to meet Achilles,

Noble Prince Achilles...

Why, I could promise to give back Helen, yes,

And all her treasures with her...

Why debate, my friend? Why thrash things out?

I must not go and implore him. Hell show no mercy,

No respect for me, my rightshell cut me down

Straight offstripped of defenses like a woman

Once I have loosed the armor off my body.

No way to parley with that mannot now

Not from behind some oak or rock to whisper,

Like a boy and a young girl, lovers secrets

A boy and girl might whisper to each other...

Better to clash now in battle, now, at once

See which fighter Zeus awards the glory!

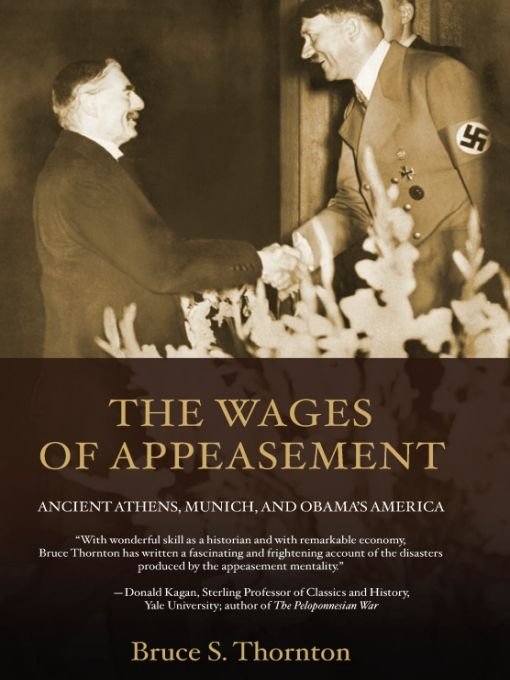

In May of 2008, President Bush ignited a political firestorm when in a speech to the Israeli parliament he compared some Democratic politicians to Englands Neville Chamberlain and his disastrous policy of appeasing Hitler: Some seem to believe we should negotiate with terrorists and radicals, as if some ingenious argument will persuade them they have been wrong all along. We have heard this foolish delusion before. As Nazi tanks crossed into Poland in 1939, an American senator declared: Lord, if only I could have talked to Hitler, all of this might have been avoided. We have an obligation to call this what it isthe false comfort of appeasement, which has been repeatedly discredited by history.

The Presidents speech and the heated reaction from the Democrats and the liberal media illustrate both how toxic the charge of appeasement can be and the iconic status of English foreign policy in the Thirties.

Likewise, the association of appeasement with Chamberlain and his policies obscures how constant in history has been the shortsighted temptation to buy off, whether with words or treasure, an enemy intent on ones destruction. But as Hectors soliloquy reveals, such temptation is as old as conflict itself and reflects the permanent truths of human nature. Appeasement, then, did not happen just once, in the England of the Thirties. It is an eternal temptation for all peoples who for various reasons lose their nerve in the face of an enemy who wants to destroy them.

As such, appeasement can be anatomized through the study of three historical examples: Athens and the other Greek city-states threatened by the ambitions of Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century B.C.; England faced with Hitlers aggression in the 1930s; and the West, particularly the United States, confronting a renascent Islamic jihad and its most powerful state sponsor, Iran. These three states share a fundamental similarity that makes comparison illuminating: they are all constitutional democracies challenged by autocratic, illiberal regimes, and some of the reasons for appeasement can be found in the very structures of democracy, as well as in the weaknesses of democratic states, that give scope to the flaws of human nature. The processes of public deliberation and decision-making, for example, are crucial for consensual governments ruled by law and procedure rather than by force. Yet these processes mean that talk is more easily substituted for action, and transient public opinion, factional interests, and irrational passions can have a warping influence on policy. Civilian control over the military can have the same effect, as the costs of conflict and impatience with setbacks can compromise policy as well.

These similarities of political culture, however, are not as important as the permanent truths of human nature expressed through social and political mechanisms. As long as the same passions and interests subsist among mankind, Edward Gibbon wrote, the questions of war and peace, of justice and policy, which were debated in the councils of antiquity, will frequently present themselves as the subject of modern deliberation. The anatomy of appeasement will take as its starting point the passions and interests rooted in human nature.

The examples of Athens and England, then, provide what the Roman historian Livy defined as historys important function : to offer from the past models of base things, rotten through and through, to avoid. Such reminders are necessary in these times, for our fight is not just against the jihadists who are using terrorist violence in pursuit of their dreams of renewed Islamic hegemony. We must also battle those in the West who, like President Obama, see appeasement disguised as diplomatic outreach as the way to neutralize the enemy. And when that enemy is the theocratic regime in Iran, for 30 years a state sponsor of terrorism with American blood on its hands, and today in the pursuit of nuclear weapons that will magnify exponentially its capability for destruction, such appeasement is indeed futile and fatal.

An anatomy of appeasement that starts with the permanent verities of the human experience, such as fear, will find no better guide to these than the Greek historian Thucydides. In his recreation of a speech delivered to the Spartans by an Athenian envoy on the brink of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides identified the three causes of conflict: fear, honor, and interest. These three motives are useful as well in identifying the causes of appeasement.

Hectors temptation to appease the Greek champion Achilles points to a one fundamental cause of appeasement. Raw fear of an enemy, whether justified or not, must be the first and most obvious factor in understanding a peoples capitulation to an aggressor, their understandable horror at the carnage of war, which he who has experienced it, the Greek poet Pindar wrote, fears in his heart its approach. The fear of death and violence inherent in human nature is a constant across time and space, as Homer shows us. Hectors fear, however, is justified, as he knows he can never defeat Achilles in battle and that his own death means the destruction of Troy. This sort of rational fear is not at issue in discussing appeasement. Suicidal resistance in the face of a more powerful enemy may be admirable, but most peoples are unlikely to choose that path. When in 846 the Pope promised the Muslim jihadists, who had already looted St. Peters and St. Pauls churches, 25,000 silver coins a year to go away, his actions werent appeasement born of irrational fear or weakness. He simply had no choice. Or when, starting in 1795, the fledgling United States paid a million dollars a year in tribute to the Barbary nations of Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis to protect American shipping and ransom hostages, the absence of a Navy made this unpleasant capitulation necessary, until the construction of a fleet allowed the U.S to end those depredations in 1815.