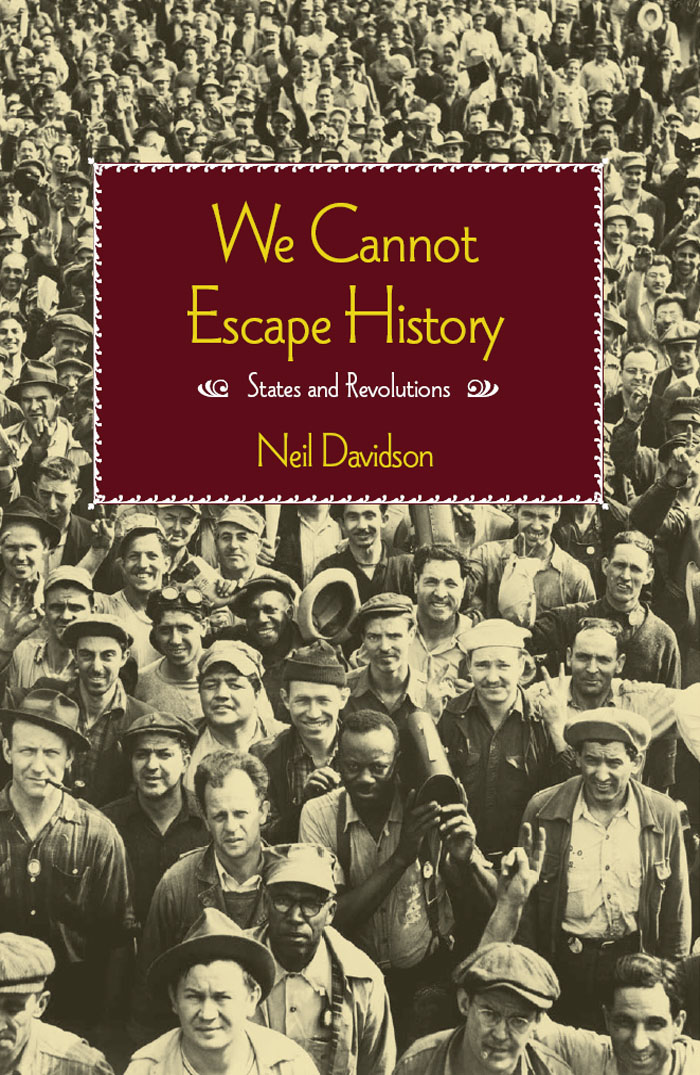

WE CANNOT ESCAPE HISTORY

2015 Neil Davidson

Published by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-506-4

Trade distribution:

In the US through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

All other countries, Publishers Group Worldwide, www.pgw.com

This book was published with the generous support of the Wallace Action Fund and Lannan Foundation.

Cover design by Eric Kerl. Cover image of a large group of workers gathered outside a factory during World War II. Copyright Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images.

Library of Congress CIP Data is available.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Michelle Campbell: some of your questions answered (at last)

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

T he preface to Holding Fast to an Image of the Past (2014) announced that a second volume of essays, called We Cannot Escape History, would appear in 2015. The book of this title that you are now reading is, however, slightly different from the one advertised. Originally subtitled Nations, States, and Revolutions, it now focuses solely on the latter two terms, and to an extent on the overarching modal transitions within which social revolutions occur. There are both practical and political reasons for this. The practical one is that, since I recently subjected the world to one 370,000-word epic (How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?), my editors at Haymarket quite reasonably felt that another book of similar size might test the endurance of all but the most dedicated readers. The political reason was that, in a way quite unexpected by me or indeed anyone else, the Scottish referendum of 2014 saw the emergence of a powerful social movement for independence, particularly in the six months leading up to the ballot of September 18. The vote was ultimately for remaining in the United Kingdom. That result is unlikely to be permanent, but in any event the extraordinary nature of the Yes campaign, the panic it produced among the British ruling class, and the transformed political landscape it left behind meant that any reflections on nation-states and nationalism must take account of these developments. A collection dedicated solely to these issues, with material on recent events in Scotland and the UK, will therefore appear later this year under the title Nation-States: Consciousness and Competition.

As in the preceding volume, the pieces included here have been reproduced with only minor alterations, such as the correction of factual errors, the rewording of ambiguous passages, the addition of material previously omitted for reasons of length, and the elimination of repetition. As with most essay collections, the contents of this one were written for a number of different outlets and occasions, but since I believe that political writing should be as rigorous as the best academic work, and that academic work should be as comprehensible as the best political writing, the chapters do not greatly vary in terms of style, although they do vary in length. The chapters are reproduced in broadly chronological order, with the exception of the section comprising chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7, which discuss individual revolutions and follow the order of their occurrence rather than when I happened to write about them. The opening and closing chapters were, however, respectively, the earliest of my writings to be delivered as a lecture and latest to be written as an article, and are directly related to each other. Chapter 1 is based on my 2004 Deutscher Memorial Prize Lecture and formed the basis of what, eight years later, would become How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? Chapter 12 is my response to criticisms of that book from comrades within the British Socialist Workers Party (SWP). The book therefore opens with one major theoretical disagreement and closes with another. The former is a debate between two traditions, those of Political Marxism and International Socialism (IS); the second is a debate within the latter tradition. The remainder of this preface explains the different contexts in which the chapters were written and concludes with my reasons for republishing them. Inevitably, then, it has some of the characteristics of a memoir.

The first section consists of a single (admittedly very long) chapter, which, as noted above, was originally a lecture given in 2004. At the time I was not employed as an academic but as a full-time civil servant for what was then the Scottish Executive (now the Scottish Government) in Edinburgh, while maintaining a marginal presence in the world of higher education as a part-time tutor/counselor for the UKs main adult distance-learning institution, the Open University. In addition to my day and evening jobs I was also a member of the SWP and an activist in my trade union, the Public and Commercial Services Union. As can be imagined, these commitments did not leave me with a great deal of spare time. Nevertheless, I managed to write and have published two books: The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (2000), which advanced the deeply unpopular thesis (at least among Scottish nationalists) that Scottish national identity only emerged after the union with England in 1707; and Discovering the Scottish Revolution (2003), which tried to establish that Scotland had undergone a bourgeois revolution between the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the suppression of the last Jacobite Rising in 1746. Both were products of a larger research project on the transition to capitalism in Scotland, which I had been conducting on free evenings and weekends for around eight years, but whichbecause of my then-publisher Plutos concerns about word count (readers may detect a theme here)was unpublishable as a single work.

I had however amassed a large amount of additional material, most of it dealing with the transformation of Scottish agriculture after 1746, that I naturally wanted to publish in some form. Early in 2003, I duly submitted it to what seemed the most suitable academic publication, the Journal of Agrarian Change. In the cover letter I mentioned that Discovering the Scottish Revolution was about to appear in print, and the editor, Terry Byres, emailed back asking if I could send him a copy of the manuscript. It turned out that, in addition to being a fellow-Aberdonian, Byres was on the jury that awarded the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize, and after reading the manuscript, he nominated it for that years award. Shortly before the 2003 lecture, at which the prize winner was to be announced, he rang me to say that it had been won jointly by me and Benno Teschke for his book The Myth of 1648the first and so far only time the jury has been unable to agree on a single winner.

Until 1996 the published version of the Memorial Prize Lecture had appeared only in