WHO LOST RUSSIA?

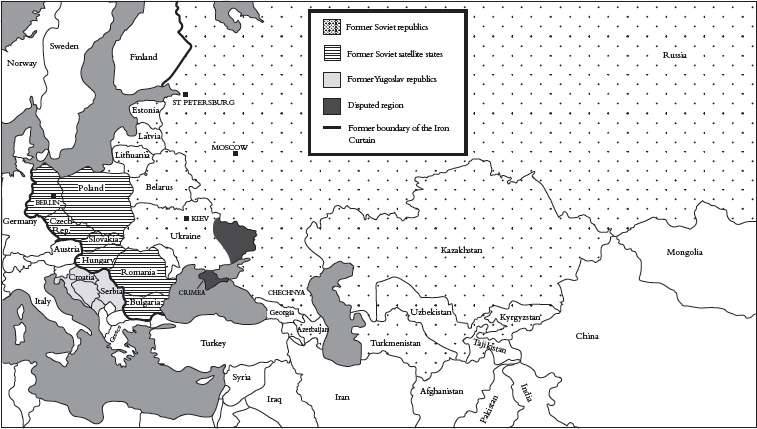

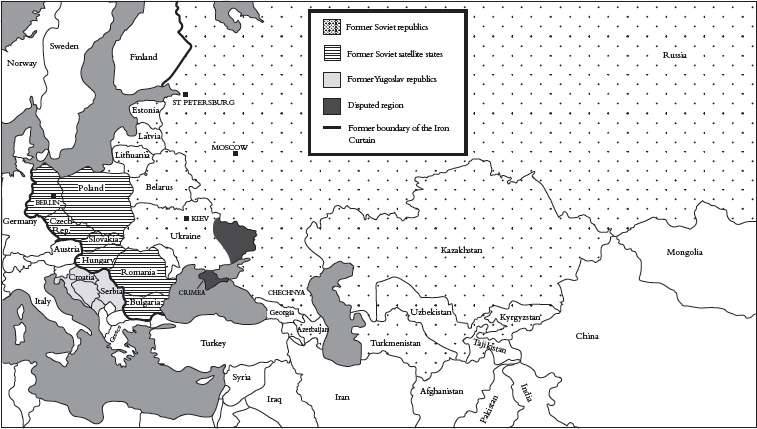

The collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 appeared to usher in a remarkable new era of peace and co-operation with the West. This, we were told, was the end of history: now the entire world would embrace enlightenment values and liberal democracy.

However, the reality was that Russia emerged from the 1990s battered and humiliated, a latter day Weimar Germany, its protests ignored as NATO expanded eastwards to take in ex-Soviet republics. Now, determined to restore his countrys bruised pride, President Vladimir Putin has overseen rapid economic growth and made incursions into Georgia, Ukraine and Syria, leaving the Western powers at a loss. A cold war threatens to turn hot once again.

In this provocative new work, based on exclusive interviews with key players either side of the new divide, Peter Conradi addresses the failures of understanding on both sides over the past twenty-five years and outlines how we can get relations back on track before its too late.

More Praise for Who Lost Russia?

Clear, thought-provoking, disturbing. Anyone who wants to understand the rise of Vladimir Putin and the resurgence of Russian nationalism should read Peter Conradis impeccably researched and impressive book.

Victor Sebestyen, author of

1946: The Making of the Modern World

How the world careened from one Cold War into another with a friendly but all too brief pit stop between them is the subject of this quite wonderful book. Bringing to bear his seven years as a Moscow correspondent, and a gift for clear, sparkling prose, Peter Conradis spirited, well-informed narrative brings to life the ups and downs, colourful characters, and turning points that didnt turn along the way.

William Taubman, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of

Khrushchev: The Man and his Era

Peter Conradi takes a calm, considered look at developments in EastWest relations that threaten to divide the world. In an era of inflamed partisan debate, he provides the historical context vital for a rational assessment of where we stand and where we are headed.

Martin Sixsmith, author of

Russia: A 1,000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East

WHO LOST RUSSIA?

HOW THE WORLD

ENTERED A

NEW COLD WAR

PETER CONRADI

Contents

To Julia

Preface

I WENT TO WORK IN MOSCOW IN August 1988 as a young correspondent for the Reuters news agency. My wife, Roberta, and I arrived in the city after a road trip across Europe and through Ukraine that took us perilously close to the Chernobyl nuclear plant, which had exploded two years earlier. Our shiny new Volvo estate car was piled so high with supplies that when we opened the back doors they began to cascade out. Stashed away beneath the jumble of clothes and shoes and household appliances were more than a hundred bottles of wine. I had been warned by my future colleagues that it was difficult to find any wine or anything much else for that matter in Russian shops. They were right.

Home was a gloomy little ground-floor flat in a complex for foreigners near the Rizhsky Market in the north of the city. Just up the road was the Exhibition of the Achievements of the National Economy (VDNKh), which by then was turning into something of a joke. A policeman in a cubicle at the gate of our compound checked the documents of everyone who came in and out. The Reuters office was in a rather grander complex in Sadovaya Samotechnaya Street, known among the expat community as Sad Sam. We wrote our stories on primitive computer terminals that turned our words into holes on a punched tape that we fed into a telex machine. A team of three interpreters, hired through the Directorate for Servicing the Diplomatic Corps (UPDK), the all-powerful organisation that took care of foreigners, watched over us in shifts. They all also worked for the KGB. At night we went to parties with an extraordinary fin de sicle feel.

When we drove around Moscow in the Volvo, now bearing number plates that began K001 K for correspondent and 001 for Great Britain we took it for granted that we were being watched. Returning home, we often found the drawer in which we kept our documents had been left open. Sometimes the phone would ring a few minutes later: there was never anyone there. Nina, who visited every morning to teach me Russian, structured her grammar questions in such a way as to extract details about my private life; she was especially interested in our Russian friends. When we wanted to travel outside Moscow we had to give our handlers twenty-four hours notice or forty-eight in the case of sensitive places to allow them time to arrange surveillance teams.

The Soviet Union, even in its final days, was a curious place in which nothing worked quite in the same way as it did in the West. But, thanks to Mikhail Gorbachev, who had come to power in 1985, it was changing fast. In the years that followed, I had a privileged front-row seat as the political, economic and socialist system built up since the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 unravelled before my eyes and something wild, new and untested emerged to take its place. There was a sense of freedom and exhilaration in the air, but also a sense of foreboding mingled with that perennial Russian fear of chaos. When I left for good in 1995 the countrys future path seemed uncertain.

The Moscow to which I returned in 2016 to research this book was a very different city. People complained about the collapsing rouble and Western sanctions and how tough life had become. But I couldnt get over how affluent the place looked compared with my time there. In the intervening two decades Russians had come to take for granted the shops, bars, restaurants and other trappings of a modern developed economy that had seemed so exotic when the first McDonalds opened in Moscow in 1990. Yet the optimism and euphoria that had reigned in my early days in the city had long since been replaced by a sense of resignation, grievance and wounded national pride.

This book sets out to track how Russia has changed over the past quarter of a century through the prism of its relations with the West. It is a story of high hopes and goodwill but also of misunderstandings and missed opportunities.

Peter Conradi

London, December 2016

Introduction

O NE AFTER THE OTHER, the SS-N-30A Kalibr cruise missiles streaked into the air, the plumes of flame beneath them lighting up the early morning skies over the Caspian Sea. There were twenty-six in total, fired in rapid succession from four Russian warships. Turning to the West, they flew for more than 900 miles across Iran and Northern Iraq at speeds of up to 600mph before hitting eleven targets near the Syrian city of Aleppo. Each missile was packed with 990lb of explosives.

It was not the most efficient or cost-effective way to hit the rebels trying to topple President Bashar al-Assad. Pentagon sources claimed that at least four of the missiles, which are similar to US Tomahawks, crashed way short of their target in Iran an assertion Moscow angrily denied. Yet it was the perfect way of showcasing Russias growing military might. Within hours, footage of the missiles launch, cut together with animated graphics of their path, appeared in a two-minute video posted on YouTube by the countrys defence ministry. The release of the video coincided with President Vladimir Putins sixty-third birthday. He made a televised appearance with Sergey Shoygu, the defence minister. The fact that we launched precision weapons from the Caspian Sea to the distance of about 1,500 kilometres and hit all the designated targets shows good work by military industrial plants and good personnel skills, said Putin, in what sounded like a sales pitch for Russian military technology.