Jill Lepore - A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States

Here you can read online Jill Lepore - A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2002, publisher: Knopf, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf

- Genre:

- Year:2002

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

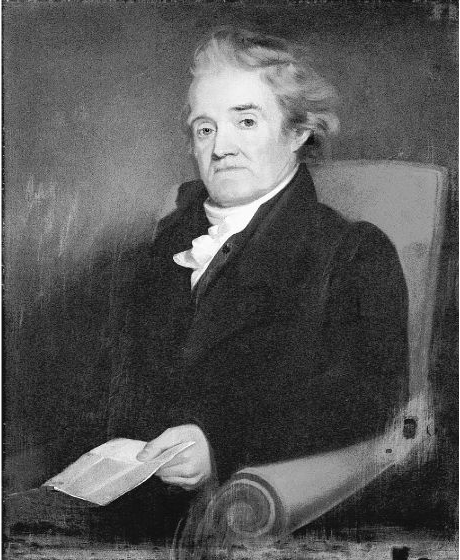

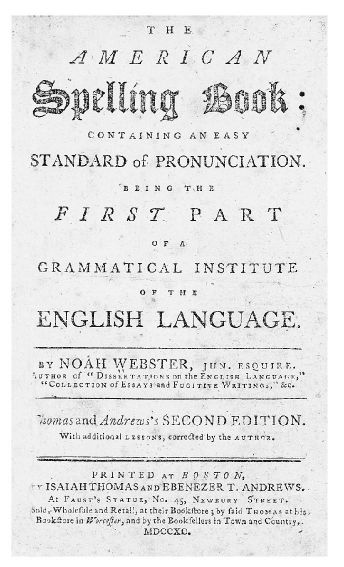

In the century following the drafting of the Constitution, Americans from Noah Webster to Samuel F. B. Morse tried to use letters and other charactersalphabets, syllabaries, signs, and codesto strengthen the new American nation, to string it together with chains of letters and cables of wire. Webster published a spelling book, hoping to teach Americans to speak and spell alike; Morse devised a dot-and-dash alphabet to link the country by telegraph.

Meanwhile, other Americans used these same tools to connect the new republic to the larger world. Caribbean-born William Thornton devised a universal alphabet, dreaming of making the world seem more nearly allied. Hartford minister Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet preached that the sign language of the deaf was a divinely inspired natural language that could help usher in the new millennium. And elocution professor Alexander Graham Bell was inspired by his fathers universal alphabet, known as Visible Speech, to invent the telephone.

Still other Americans used letters and other characters to distance themselves from the United States. Cherokee silversmith Sequoyah invented an eighty-five-character syllabary for the Cherokee language to promote his peoples independence; Abd al-Rahman Ibrahima, an aging slave in Natchez, Mississippi, demonstrated his Arabic literacy to gain both his freedom and his passage back to Africa.

In A Is for American, Jill Lepore tells the tales of these seven unusual charactersWebster, Thornton, Sequoyah, Gallaudet, Abd al-Rahman, Morse, and Belland their efforts to use language to define national character and shape national boundaries. Taken together, these superbly told stories, ranging from the Revolution to Reconstruction, reveal the daunting challenges faced by a new nation in unifying its diverse people.

Jill Lepore: author's other books

Who wrote A Is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.